“Mrs. Käsebier is answering the question whether the camera can be substituted for the palette.”

-A. Horsley Hinton, “Mrs. Gertrude Käsebier’s Portrait Photographs. From a Painter’s Point of View” Camera Notes, July 1899.

At the core of the extensive collection of Pictorialist photography in the Museums is a group of 166 photographs by Gertrude Käsebier. When taken together with the holdings of Käsebier-related papers in Special Collections, the University of Delaware Library, Museums, and Press is a major resource for scholars and enthusiasts of one of the most prominent photographers in the Pictorialist movement.

Käsebier began studying art and then later photography relatively late in life, following an unhappy marriage and the birth of three children. She and her husband never divorced, but they lived separately in her later life. At the age of thirty-seven, in 1889, she started studying painting at the Pratt Institute, and later in the mid-1890s she began her photography career, opening her own photographic portrait studio in New York around 1898. She was particularly famous for her images of women and children. Alfred Stieglitz recognized her talents early and included her work in both Camera Notes and Camera Work, and she was an important member of the Photo-Secession.

The collection of photographs by Käsebier in the Museums includes a range of examples showing the photographer experimenting with different printing techniques applied to the same image. This pairing of two versions of Untitled [Woman and Children with Horse] provides an opportunity to compare Käsebier’s use of gum bichromate (top) and platinum (bottom) for the same image. Gum bichromate printing is well-suited to creating soft and atmospheric visual effects and is a particularly labor-intensive process requiring an especially skilled practitioner.

Platinum was Käsebier’s preferred technique and was associated with Pictorialism in general. Much like the gum bichromate process, platinum printing is helpful in creating a soft atmosphere in a photographic image. There are subtle differences in appearance between the two methods when seen side-by-side.

The Heritage of Motherhood demonstrates Käsebier using photography as an emotionally impactful, expressive medium. The image depicts a mother in mourning; the subject is writer Agnes Lee who had lost a daughter. Lee’s ambiguously mournful facial expression with eyes closed, combined with the shadowy look to the print’s surface and rocky landscape, create a somber scene. Käsebier deliberately manipulated the gum bichromate printing process to create the mottled appearance of the print where details and edges of forms are all muted and dissolving. The print is in contrast to the original glass plate negative (housed at the Library of Congress), which is crisp, clean, and highly detailed. This emphasizes that the soft look of Pictorialism here was accomplished in the printing process and not in the act of snapping the photograph.

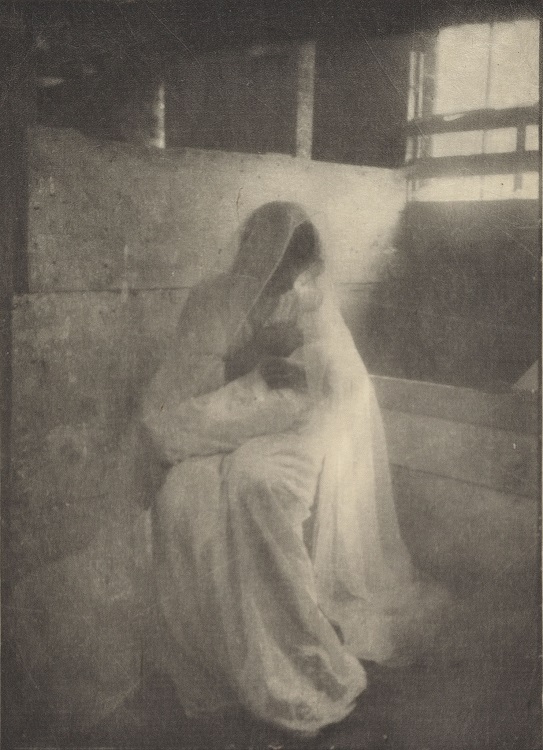

Käsebier composed this image to have religious, specifically Christian, associations that she reinforced with the title, The Manger. The depiction of a woman in a diaphanous white gown and veil cradling an infant in a barn is a particularly strong example of the soft look of Pictorialism, filled with diffuse light and shadow. Upon first glance, it would be easy to mistake this image for a delicate charcoal or chalk drawing. This photograph was among the selections of Käsebier’s work that Alfred Stieglitz chose to include in the first issue of Camera Work in 1903. The photogravure technique seen here was one of the main methods of disseminating Pictorialist photographs in the iconic journal.

![Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934), Untitled [Woman and Children with Horse], n.d., gum bichromate. Museums Collections, Gift of Mason E. Turner, Jr. Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934), Untitled [Woman and Children with Horse], n.d., gum bichromate. Museums Collections, Gift of Mason E. Turner, Jr.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/women-in-pictorialist-photography/wp-content/uploads/sites/231/2022/04/3_Kasebier_Woman_and_Children_with_Horse_Gum.jpg)

![Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934), Untitled [Woman and Children with Horse], n.d., platinum. Museums Collections, Gift of Mason E. Turner, Jr. Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852-1934), Untitled [Woman and Children with Horse], n.d., platinum. Museums Collections, Gift of Mason E. Turner, Jr.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/women-in-pictorialist-photography/wp-content/uploads/sites/231/2022/04/4_Kasebier_Woman_and_Children_with_Horse_Platinum.jpg)