Amy Hicks

Imaginary Labor

2021

Multi-channel HD video installation, looped

Courtesy the artist

What kinds of labor does our society value, and who benefits? What could happen if we inhabited a different social structure that prizes creativity, that values people for being imaginative and rewards modes of production not necessarily tied to financial profit?

In creating this video installation Amy Hicks started with found footage of assembly-line and domestic labor. She digitally removed the workers from their environments, using the Content-Aware Fill function in Photoshop, and then assembled them together within a separate, void-like video space. In the resulting videos the industrial products appear to assemble themselves, while the gestures of the workers’ labor are opened up to new possibilities and imaginative ends. Viewers might envision what the workers could be making as well as how new opportunities for creative production could differently shape our society.

René Marquez

left

from the series, For the dog sitter

2019-20

Six digital prints of video stills from the video series

As part of his project centered on the Free to Be Dog Haven sanctuary, René Marquez creates videos showing different aspects of the dogs’ daily lives. Here, six stills from his videos series For the dog sitter complement the painting Studio, 2003, showing different aspects of the artist’s overarching project. In his videos Marquez plays with the documentary format to challenge conventional narratives and representations of animals that center on human perspectives. Marquez constantly asks: “Is there a different way to think about how we live with our animals? Is a dog always a ‘pet’ or is there a different way to think about what this means?” His videos and paintings invite viewers to contemplate the same questions.

Mission Statement for Free to Be Dog Haven:

To provide a home and quality of life for dogs who may face challenges living with humans. The sanctuary is an ongoing investigation into multi-species cohabitation and collaboration: how can different species live together in full acknowledgment of each other’s subjectivity and agency? The implications of this investigation, while exploring human-non-human interaction, address human-human interaction as well.

right

Studio

2003

Oil and acrylic on canvas

Through his sensitive paintings of dogs, René Marquez examines how humans can see animals as individual, sentient beings without anthropomorphizing them. This painting of two reclining dogs in a nearly abstract human-built interior is an early part of the artist’s interdisciplinary practice. At the core of this practice is Free to Be Dog Haven, a dog sanctuary he founded in 2011. The sanctuary, also his home, is a site of investigation where the co-habitation of dogs and humans engages his longstanding questions about postcolonial identity. Typically, in human-dog relationships, humans are “masters,” and dogs are “pets.” The sanctuary aims to create a collaborative living situation that allows the animals to be themselves. Marquez acknowledges the challenge—dogs are the products of human intervention, as they result from thousands of years of breeding. He likens this situation to colonization: as it is impossible to extract 400 years of Spanish influence in the Philippines (Marquez’s birth country) or to return to a time before slavery, it is also impossible to fully extract humanity from the dogs. Through this analogy Marquez explores a question of how we can reorient present societies in ways that recognize colonial histories without being shaped by them.

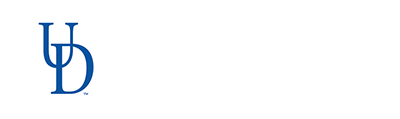

David Meyer

According to What

2020

Steel

Courtesy the artist

David Meyer’s exploratory approach to working with steel, a material typically regarded as unyielding, begins in a place of play. For According to What, he starts by cutting 3/8-inch steel rods into segments and cold forming the ends into hooks that can link together. He creates rules for himself about how to connect the rods and then promptly disobeys those rules, as he adjusts his actions according to what the material itself wants to do. He likens his dynamic process to a kind of dance with the material: the artist tries certain moves, and the form evolves as the material yields or pushes back. Yet, he considers the ultimate participants in the work’s creation to be viewers, who perceive and interpret its materiality and abstract form according to their own embodied experiences and subjective associations.

David Brinley

left

Resist

2019

24-layer serigraph on Cranes archival cotton rag

Courtesy the artist

As a fine artist and illustrator David Brinley draws inspiration from a variety of sources, including vintage ephemera. Resist represents a contemporary spin on American illustrator Harry R. Hopps’s iconic WWI recruitment poster Destroy this Mad Brute: Enlist (ca. 1917). Hopps’s poster features a barbaric gorilla holding a bloodied club labeled “Kultur” (German for “culture”) in one hand and a partially-disrobed woman in the other. Brinley reimagined the image as an allegory for the Trump era, replacing the gorilla’s face with the 45th President’s, the naked woman with Lady Liberty, and the word “Enlist” with “Resist.”

right

Dynamite on the Train

2019

Cover illustration for Pakn Treger: Magazine of the Yiddish Book Center

Acrylic on watercolor paper and digital

Courtesy the artist

David Brinley’s interests in folk art and the aesthetics of self-taught artists influences in his occasional use of symbols and allegory to create scenes and suggest narratives. Dynamite on the Train alludes to the story of Klara Klebanova, a young Russian Jewish revolutionary who, in 1905, smuggled dynamite onto a train beneath her clothing. Brinley created the image as a cover for the magazine Pakn Treger as part of a special issue entitled “‘Dynamite on the Train’ and Other Memoirs by Jewish Women” (2019). The artist was honored as a winner of American Illustration 39 (2020) for this image.

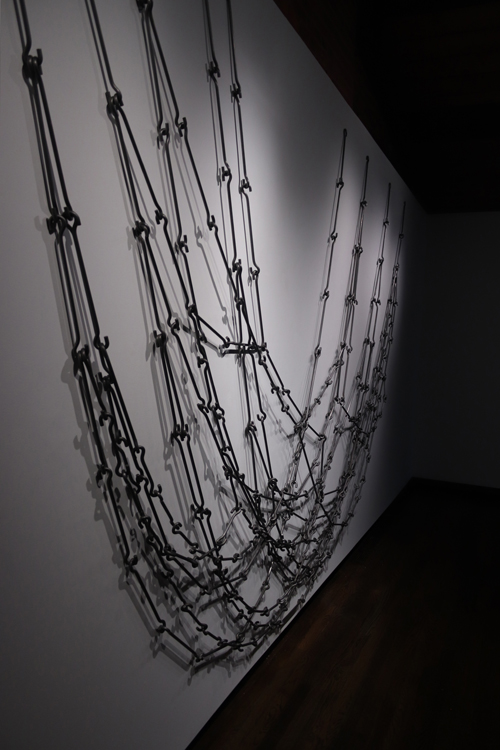

Ashley John Pigford

Assistive Devices for People with Physical Disabilities

2020

Video

Courtesy the artist with special thanks to Ewa Okla, Kahlani, Nemours A.I. duPont Hospital for Children, and Art Therapy Express

This video provides an introduction to designer Ashley Pigford’s work creating assistive devices for people with special needs. Pigford’s user-centered design process often starts with specific individuals, as he evaluates their unique abilities and circumstances and develops tools to help them with aspects of daily living. For example, he created a foot-activated highchair with a mechanical spoon that enables a child born without arms to eat independently. “Push and Draw” is an example of a product Pigford designed for broad public use. Made of two Plexiglas disks suspended by springs with a pencil or marker through the center, it enables users without fine motor control to write or draw by pressing on the disk with their wrists or other body parts. The implement has been used in art therapy as an expressive tool and in a children’s hospital to help kids with special needs learn to write at age-level curriculum.

For Pigford, the goal of design is not only to create objects, but more importantly to understand how these things function in people’s lives. As he says: “making matters.”