African American poets have asserted their blackness with joy, with defiance, occasionally with bitterness at the pressure to downplay Black identity or hide it behind a protective mask. How do the voices and personae in African American poetry express the richness, depth, and variety of African American identity? What sorts of expressive (and subversive) freedoms do poetic personae and masks make possible?

Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906)

Dunbar was one of the most celebrated and popular African American poets during his lifetime, as attested by this 1899 New York Times article that proclaims him the "Orpheus of his Race" and celebrates his marriage to fellow writer Alice Ruth Moore (later Alice Dunbar Nelson). Dunbar’s early dialect poems attracted international acclaim from white critics. Their narrow interest constrained the reception of Dunbar’s work, yet his oeuvre includes novels, short stories, essays, and poetry collections that demonstrate expressive skill and technical mastery. One of Dunbar's best known poems, "We Wear the Mask" (from Lyrics of Lowly Life, 1896), articulates the need to maintain a protective distance between public persona and private experience:

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

Although Dunbar embraced admirers' view of his marriage to Alice as "this Mr. and Mrs. Browning affair," in reality the relationship was tumultuous and punctuated by acts of violence. Paul and Alice were married in 1898 and separated by 1902. Following years of ill health, Dunbar died in 1906, at the age of thirty-three.

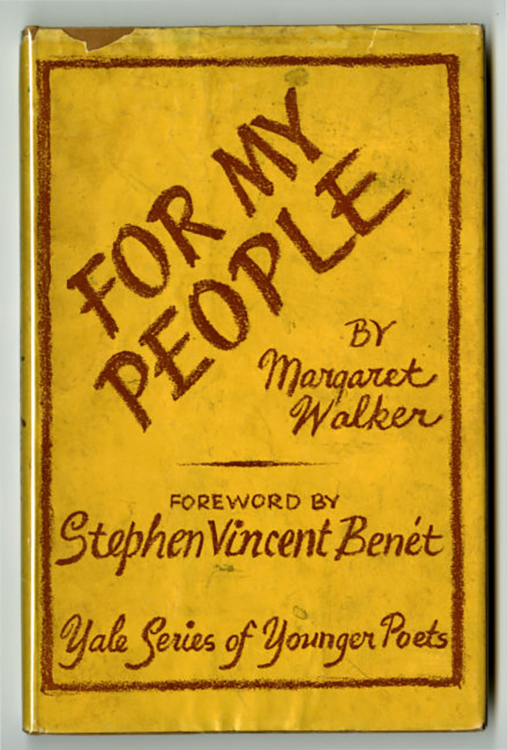

Margaret Walker (1915–1998)

Born and raised in a period when segregation and discrimination were legal in the American South, Walker wrote poems demanding civil rights and celebrating the language and culture, struggles and triumphs of African Americans. Coming to prominence as a member of Chicago’s South Side Writers’ Group, Walker received the honor of having her first collection, For My People, published as part of the Yale Series of Younger Poets. In this volume, the poet claims her identity as "a child of the valley" with "roots [that] are deep in southern life," asserting her desire to find "rest unbroken" and the freedom to sing a "careless song" in her southern homeland without the constant threat of racist violence. Composed of sonnets, ballads, and lyrical portraits, the collection demonstrates her mastery of form and, while acknowledging struggle and suffering, offers cultural and racial affirmation. Walker continued to publish poetry and prose for the next fifty years.

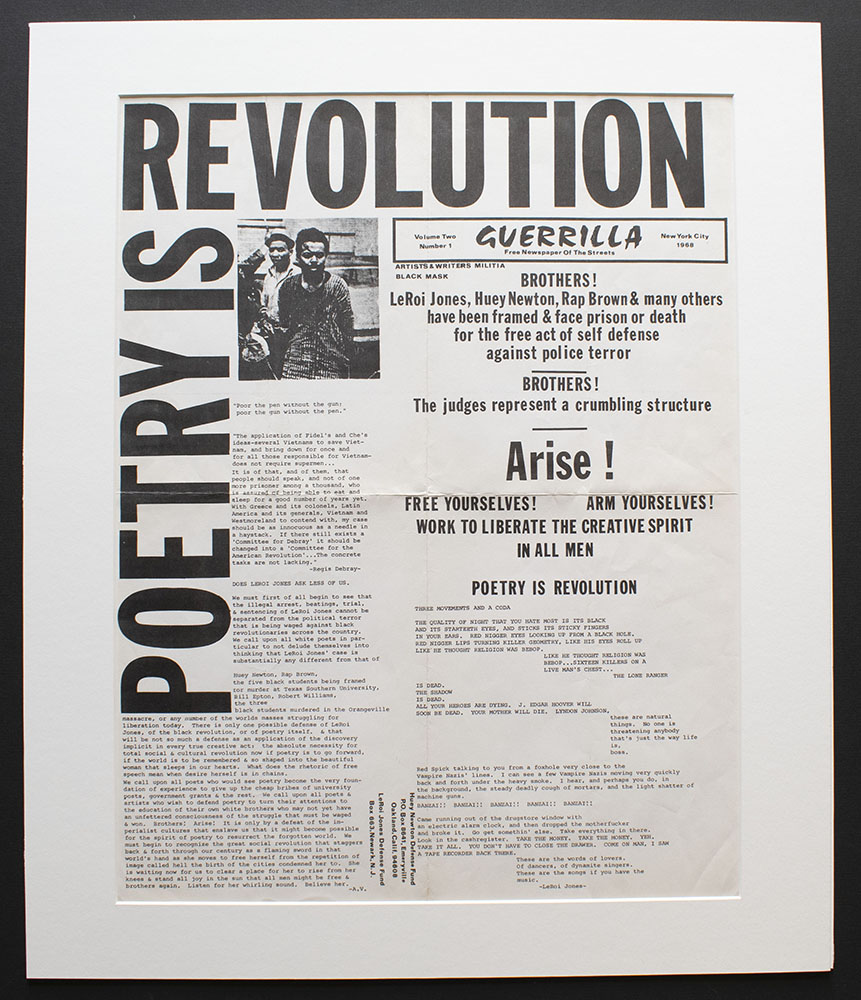

Amiri Baraka (1934–2014)

Amiri Baraka, known early in his career as LeRoi Jones, was a widely published African American writer of poetry, drama, fiction, essays, and music criticism. From the late 1950s to the mid-1960s, Baraka was part of the Beat movement in New York, working closely with Allen Ginsberg and Diane di Prima, with whom he had a daughter. After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, he embraced Black nationalism, leaving his white wife Hettie and their two daughters, moving to Harlem, and changing his name. In Harlem he founded the Black Arts movement, rejecting affiliation with predominantly white culture in favor of Pan-Africanism and cultural self-determination. Guerrilla, a free paper published by the Detroit Artists Workshop, juxtaposes Baraka's arrest at the 1967 riots in Newark, New Jersey, with the political prosecutions of Black Panther Huey Newton and activist H. Rap Brown. In the mid-1970s, Baraka distanced himself from Black nationalism and began to espouse Marxism-Leninism and to support interethnic liberation movements. Deliberately provocative, Baraka stood as a polarizing figure throughout his career, with some critics representing his work as violent, anti-Semitic, misogynistic, and homophobic.

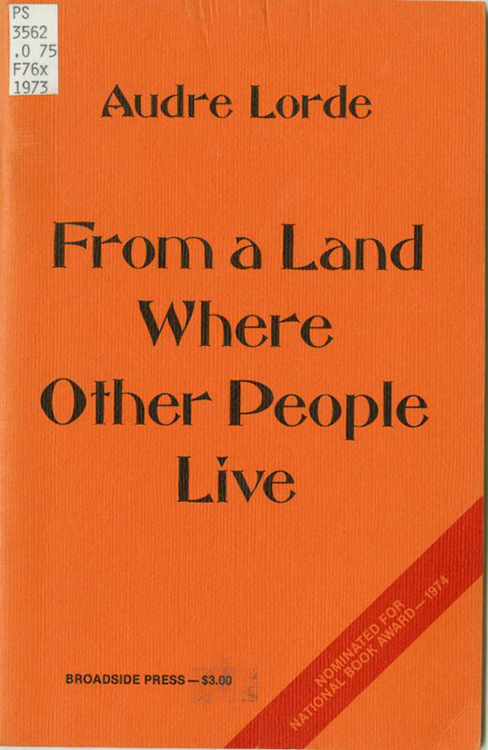

Audre Lorde (1934–1992)

Lorde claimed her poetic identity as a young child when she changed the spelling of Audrey to create a near visual rhyme between her first and last names. During her career, she asserted the intersectionality of her identity, introducing herself at public appearances as a “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” In From a Land Where Other People Live, the poem “Who Said It Was Simple” expresses dissatisfaction with social movements that prioritize one facet of the speaker’s identity over another:

...I who am bound by my mirror

as well as my bed

see causes in color

as well as sexand sit here wondering

which me will survive

all these liberations.

Lorde's significant body of work extends beyond her nine poetry collections. The Cancer Journals (1980) is regarded as a major work of illness narrative, while Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982) is a "biomythography" of her early years that offers a compelling image of lesbian life in 1950s New York. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984) has become a canonical text for Black studies, women’s studies, and queer theory.

![“Orpheus of His Race” [newspaper clipping]. Scrapbook No. 1, circa 1890-1934. Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.12.233. “Orpheus of His Race” [newspaper clipping]. Scrapbook No. 1, circa 1890-1934. Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, MSS 113.12.233.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/lift-every-voice/wp-content/uploads/sites/232/2020/11/orpheus1.jpg)