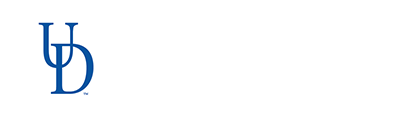

The kind of display originally intended for sacred objects differs from that of artwork made for galleries and museums. Christian icons and crucifixes were used both in public processions or worship services; they were also used by individuals in private homes and smaller versions were worn or carried on the body. Icons invited the touch of the hand or the kisses of those who wished to connect with the holy. To ensure these objects glorified God and not the maker’s skill, most makers remained anonymous. Similarly, African masks, figures, and instruments functioned through public ritual performance to strengthen social bonds or as personal spiritual items forbidden from public view.

9.

Unknown Painter (possibly Russian)

St. Sergius of Radonezh

19th century

Oil on wood

Museums Collections, Gift of Burgess-Jastak Foundation

Christian icons are thought not only to represent a holy person, but to contain the presence of the figure depicted, and are therefore considered sacred. Commemorated in this icon is St. Sergius (b. 1314), one of the most venerated saints of the Russian Orthodox Church. His life is separated into discrete moments framed individually, surrounding the central image. This method of visual narrative became popular for fifth-century ivory Gospel book covers and continued to be employed in Christian artwork throughout the centuries.

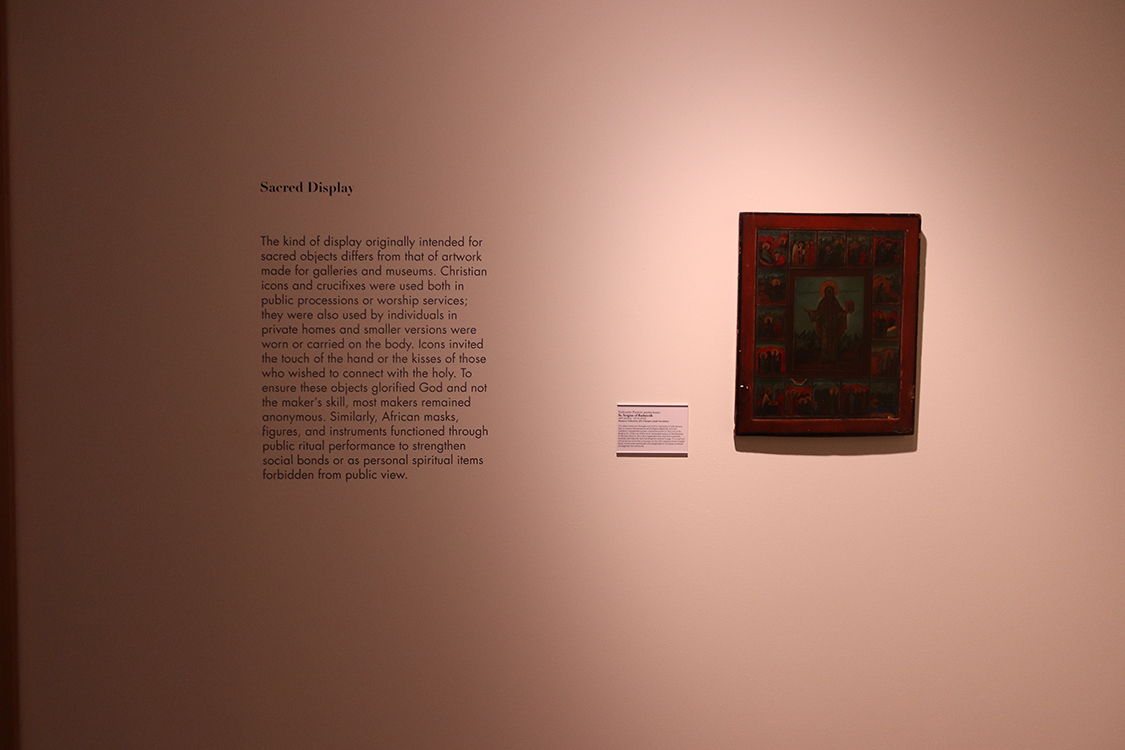

10.

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910-2007)

Revelation of St. John (The Lamb & Seals)

1994

Engraving

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

Allan Rohan Crite was eighty-four years old when he produced fourteen scenes from the Revelation of St. John, a testament to his legacy of religious artwork. A devout Episcopalian, Crite’s subject matter began to center around religious themes in the late 1930s. In nearly every scene from his Revelation cycle, groups of figures are drawn as if stacked upon one another, and numerous moments of a narrative are packed within a single pictorial space. This method of visual narrative is similar to that of the St. Sergius icon in this exhibition, demonstrating Crite’s thorough study of medieval and Renaissance artwork. Crite’s sophisticated biblical visions incorporate the Black figure, challenging equations of Black Christian identity with working- or lower-class African Americans and revealing a wider spectrum of Black religious experience.

11.

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910-2007)

Revelation of St. John (Lamb/Foreheads)

1994

Engraving

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

12.

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910-2007)

Revelation of St. John (Heavenly Bride)

1994

Engraving

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

13.

John Anasa Thomas Biggers (American, 1924-2001)

Two Kneeling Figures

1994

Lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

14. -top

Francesco Bartolozzi (Italian, 1727-1815)

St. Bartholomew Receiving Golden Apple from the Virgin

c. 1747-1815

Engraving

Museums Collections, Gift of Mrs. John Sloan

15. -bottom

Léopold Flameng (French, 1831-1911)

Vision

1861

Etching

Museums Collections, Gift of Mrs. John Sloan

16.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Angel Appearing to the Shepherds

1634

Etching

Museums Collections, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. George B. Tatum

Although this image was first printed in 1634, this printing is a later impression made using the same plate which had been reworked to restore worn down sections.

17.

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910-2007)

Revelation of St. John (The Vial & Fire)

1994

Engraving

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

18.

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910-2007)

Revelation of St. John (The Angel)

1994

Engraving

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

19.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Descent from the Cross

1633

Etching

Museums Collections

Although this image was first printed in 1633, this printing is a later impression made using the same plate which had been reworked to restore worn down sections.

20.

Georges Rouault (French, 1871-1958)

Christ Seated

1949

Mixed intaglio

Museums Collections

21. -top left

Arturo Lindsay (Panamanian, b. 1946)

Minkah of Kumasi

2001

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

22. -top right

Arturo Lindsay (Panamanian, b. 1946)

Kanza of Kwango

2001

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

The names and faces of the countless people who perished during the Middle Passage of the trans-Atlantic slave trade have been lost. Using the aesthetics of Santería, Arturo Lindsay returns them to us. Santería, loosely translated “the way of the saints,” originated when West African Yoruba disguised their Orisha (holy entities) as Roman Catholic saints to conceal their own religious practices.

Each youth pictured here is individualized with their own name, village, and physical features. Like Christian saints, the figures are haloed and framed beneath an arch, punctuated by images of shackles and ships - the instruments of their imprisonment - and Yoruba symbols. Like icons, their living presence is recovered and preserved in their image. Lindsay’s series functions as not only commemoration and veneration of the dead. Through the vehicle of art, he endeavors to bestow peace on the spirits of those who met tragic ends and healing for those of the African diaspora who continue to suffer.

23. -bottom left

Arturo Lindsay (Panamanian, b. 1946)

Umar of Ségou

2001

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

24. -bottom right

Arturo Lindsay (Panamanian, b. 1946)

Oni of Lagos

2001

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

25.

Cecil Bernard (American, b. 1951)

Three Crosses

2000

Mixed media on burlap

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

26.

Camille Billops (American, 1933-2019)

Fire Fighter

1990

Mixed intaglio

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

Camille Billops’s profound belief in the power of memory and representation are reflected in her bold depictions of family. She dedicated several works to one of the most influential women in her life, her godmother. Known to the family as “Mom,” her godmother died when Billops was twelve years old. The cross on Mom’s arm disrupts the repeating stripe pattern, signifying her untimely passing. The tight cropping of the composition creates a feeling of tension, reflecting the intense connection between goddaughter and godmother that supersedes death, the power as an ancestor who can be summoned from the other realm to put out the fires of strife.

27.

Unknown Carver (possibly Europe)

Corpus from Crucifix

17th century

Ivory and bone

Museums Collections, Gift of David W. Baldt

28.

James W. Donaldson (American, b. 1944)

Black Jesus, Cross and Thorns

1968

Oil on board

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

The image of the Black Jesus operates as a critique of the culture of whiteness in which it is embedded. Similar to his portraits of important figures in the Civil Rights movement, Donaldson’s image embodies the search for full inclusion, specifically in the Christian faith. While relying on recognizable implements of Jesus’s crucifixion, Donaldson paints them in a personal style quite removed from historically traditional portrayals of Jesus. Jesus’s body leans backward into a riot of brushstrokes as if reeling under the weight of his cross. His upturned gaze draws the viewer’s eyes to the crown of thorns biting his scalp. Through the Black Jesus, the suffering of African Americans is mirrored, valorized, and threaded with hope in that, like Christ, they will rise again.

29.

William (Bill) Walker (American, 1927-2011)

Study of Two Nuns

c. 1960-1970

Oilstick on board

Museums Collections, Given by an Anonymous Donor in Honor of Dr. Ann Eden Gibson

30.

Unknown Artist (Italian)

Saint Jerome

17th century with later alterations

Ceramic

Museums Collections, Gift of Mr. Allan Gerdau