The Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s viewed art as a vehicle for the cultural liberation and spiritual care of the Black community. Members of the movement embraced their African origins as a source of inspiration for works that critiqued the Western aesthetic and brought a distinctly African American aesthetic into being. Black artists began traveling to the African continent, not only to view objects and rituals, but to glimpse behind the mask at the concepts that generated and animated those external forms. The intersection of form, function, history, and culture continues to inflect the work of contemporary African American artists.

31.

Willie Cole (American, b. 1955)

The Ogun Sisters

2012

Serigraph

Museums Collections, Gift of Curlee Raven Holton, Director, Experimental Printmaking Institute Lafayette CollegeBound under the theme of iron, this assemblage of symbols communicates ideas of repetition, servitude, and resilience. Surrounded by a border stamped with the brands of an electric iron, a mirrored image of a uniformed woman ironing hints at the repetition of labor. Identical masks of the Dan people of Liberia and the Ivory Coast obscure the women’s faces, suggesting the invisibility of Black people in domestic service. But the strength of iron also permeates the composition. The Haitian sign for Ogun, the Yoruba deity of metal (iron) dominates the top of the print. At the bottom, the chemical element of iron is represented as a mix of protons and neutrons, smaller echoes of the symbol circling over the hearts of the two women.

32.

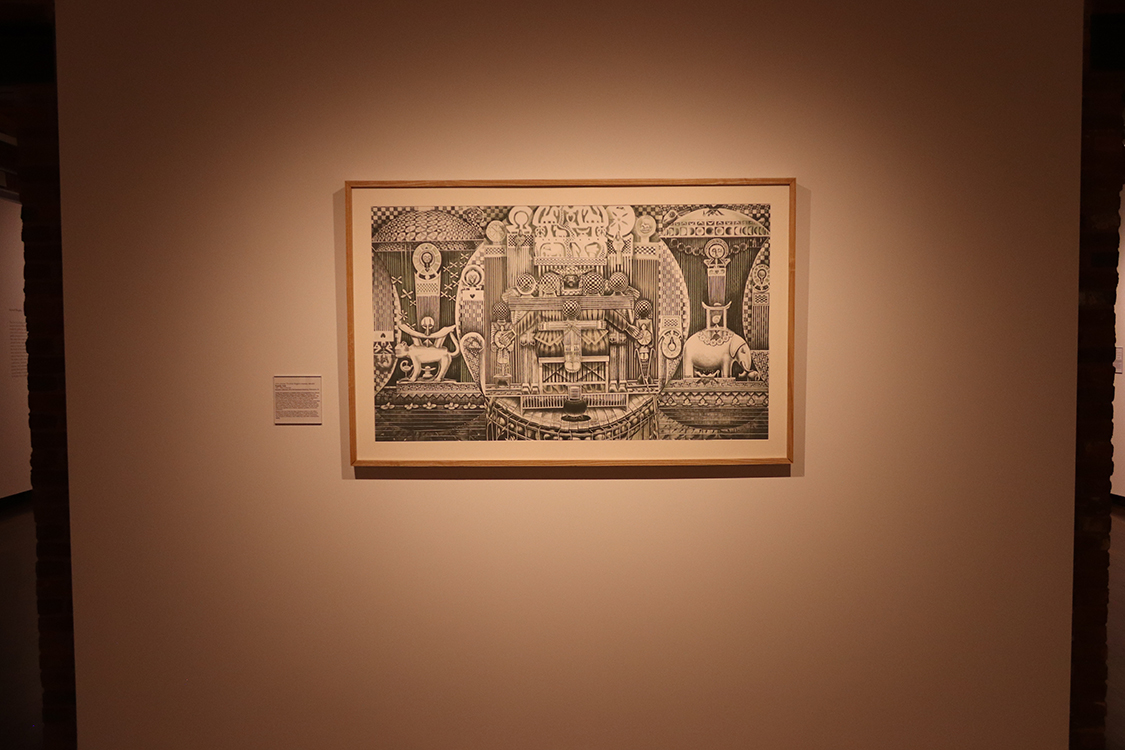

John Anasa Thomas Biggers (American, 1924-2001)

Family Ark (Monochrome)

1992

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

Family Ark represents a complex fusion of iconography from African and African American history, art, and religion. Geometry and pattern perform various feats of visual metaphor and allusion. The print’s three-panel format evokes a triptych made for placement over an altar in a Christian church. In the central panel, the symmetrical forms of the family at prayer unite to create a new form itself resembling an altar. A child kneeling simultaneously floats like a hanging crucifix. Arms wide in blessing like a priest, the only figure who faces us may be the family’s matriarch. Yet, her horned head-wrap signifies she is Hathor, Egyptian goddess of love and protection.

Biggers was one of the first Black American artists to visit Africa to study its cultures and their traditions. A recurring aspect of his art involves merging the African experience with its involuntary reincarnation in America, and coalescing myth with contemporary reality.

33.

Unknown Painter (possibly Russian)

Feodorskja Madonna

19th century

Tempera on wood panel with silver enameled frame

Museums Collections, Gift of Burgess-Jastak Foundation

34.

Allan Rohan Crite (American, 1910-2007)

The Christmas Spiritual

c. 1940

Silkscreen

Museums Collections, Given by Lawrence Hilton in Honor of Paul R. Jones

35.

Xenobia Bailey (American, b. 1955)

Urban Mystic

2015

Linoleum cut

Museums Collections, Given in honor of James E. Newton by Julie L. McGee

36.

David Clyde Driskell (American, 1931-2020)

Her Hat Was Her Halo

2007

Monotype, relief

Museums Collections, Gift of Experimental Printmaking Institute, Lafayette College

In this print, shards of color proliferate the white linework like facets of stained glass. The circular format reinforces this association, recalling glass roundels and saint’s portraits. The fiery outline encircling the figure’s head blurs the distinction between hat and halo, emphasizing the head as the entry point for power and enlightenment. In the United States, the tradition of adorning the head for worship evolved from African headdresses to ornate church hats. Raised in the church, Driskell’s art was inspired by both his father’s Christian drawings and paintings and his grandfather’s African-styled sculptures.

37.

William Etienne Pajaud (American, 1925-2015)

Sunday A.M.

2002

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

38.

Paul F. Keene, Jr. (American, 1920-2009)

Solomon’s Bride

1980

Silkscreen

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

“I am dark and lovely,” declared King Solomon’s bride in the Hebrew love poem, the Song of Solomon. The woman in this image is also dark, and ornamented like a queen. As in many of Keene’s images, the figure’s head is haloed, and like a holy icon she stands frontally within a frame. But the frame also suggests a window. Its small size and offset placement creates a solemn mood of isolation, a feeling Solomon’s bride knew all too well as she roamed empty streets in the night, searching for her love.

39.

Unknown Painter (possibly Russian)

Transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor

19th century

Tempera on wood

Museums Collections, Gift of Burgess-Jastak Foundation

The Transfiguration of Christ represents the visionary experience of his followers Peter, James, and John. The men watch as Christ is enveloped in a mandorla (body halo) and converses with apparitions of Old Testament prophets Elijah and Moses. Not only is Christ transfigured, but the vision of the apostles are transfigured, allowing them to perceive his true glory. They are able to see Christ as the connecting point where human nature meets God and the temporal touches the eternal.

40.

Michael D. Harris (American, b. 1948)

Mothers and the Presence of Myth

1994

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

In this tribute to the power of mothers and their blessings, Harris draws from Yoruba culture—one of the major foundations of African American traditions. Birds, as celestial messengers, represent women’s spiritual power. The word àse (upper right) represents the power to make things happen and produce change (often symbolized by a snake or zigzags), dúpé ò means “we give thanks,” and oriki fún awon iy wa translates to “praise song for our mothers.”

41.

Edgar Sorrells-Adewale (American, b. 1936)

The Laying on of Hands is a Time-Honored Ritual

1997

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

42.

Imaniah Shinar (born James E. Coleman)

Man

2001

Graphite and colored pencil on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

Visual and textual allusions to Judaism and esoteric symbols are woven throughout this drawing. Reminiscent of the Jewish high priest described by scribe Ben Sira, the man in this drawing appears “Like the rainbow appearing in a cloud… When he donned the robes of honor, Wore his splendid garments.” Gems, like those adorning a priest’s shoulders and breastplate, tumble down the man’s right side. The gold twisting around the blue stone of the headpiece nearly quotes the Magen David, also known as the six-pointed Star of David. The image of a Black man dressed in Jewish symbolism may allude to African Americans as an oppressed people in need of exodus from the modern Babylon of the United States. This may also be reflected in the artist’s adopted surname, “Shinar,” which is the ancient Hebrew for an area including Babylon.

43.

Dolphus (Damballah) Smith (American, 1943-1992)

Faces

1974

Mixed media

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

44.

Martin Payton (American, b. 1948)

Portal

1990

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

45.

Senufo Carver (West Africa)

Face Mask, Twin (Kpelie)

c. 1900-1960

Wood

Museums Collections, Gift of Dr & Mrs. Willi Riese

All masquerades among the Senufo are performed by males, are associated with men's activities in the Poro society, and are, in general, an expression of male roles and prerogatives. The incorporation of female-oriented images and symbols in the male-controlled arts of masquerades is a hallmark of these activities. The significance of twin-faced kpelie masks is not well understood, but twin and single-faced kpelie are used interchangeably in Senufo rituals.

46.

Baule Carver (Côte d'Ivoire)

Seated Female and Infant

20th century

Wood

Museums Collections

In the realm humans inhabit before birth, everyone is married. According to the Baule people of Côte d'Ivoire, spirit spouses can follow their husband or wife into this world and affect their daily lives for good or for ill. More rarely, a spirit spouse can be used to aid a diviner in fortune telling. To ensure a spirit’s cooperation they are given sculptural form, dressed, and kept in the home. Spirit wives are adorned with distinctive scarifications and finely groomed hairstyles. The addition of a child affirms her worth and status as a mother.

47.

Dan Carver (Liberia, Africa)

c. 1960-1990

Wood, fiber, metal

Museums Collections, Gift of Geneva R. Steinberger

48.

Senufo Carver (West Africa)

Face Mask (Kpelie)

20th century

Wood

Museums Collections, Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Kurt Delbanco

The kpelie mask is used in Senufo rituals at initiation ceremonies, funerals of important villagers, and at harvest festivals. Though worn by men, the kpelie’s small oval face, elegant features, and scarification marks represent the ideal female. Fertility symbols such as palm nuts or vulvas relate to initiation ceremonies. Both the dance performed by the man and the mask itself are intended to embody the beauty of a young woman. The figure on the head represents sacred animals such as the antelope, ram, or hornbill. The leg-like pendants below the face are a stylized rendering of the hairstyle worn by women who have borne children.