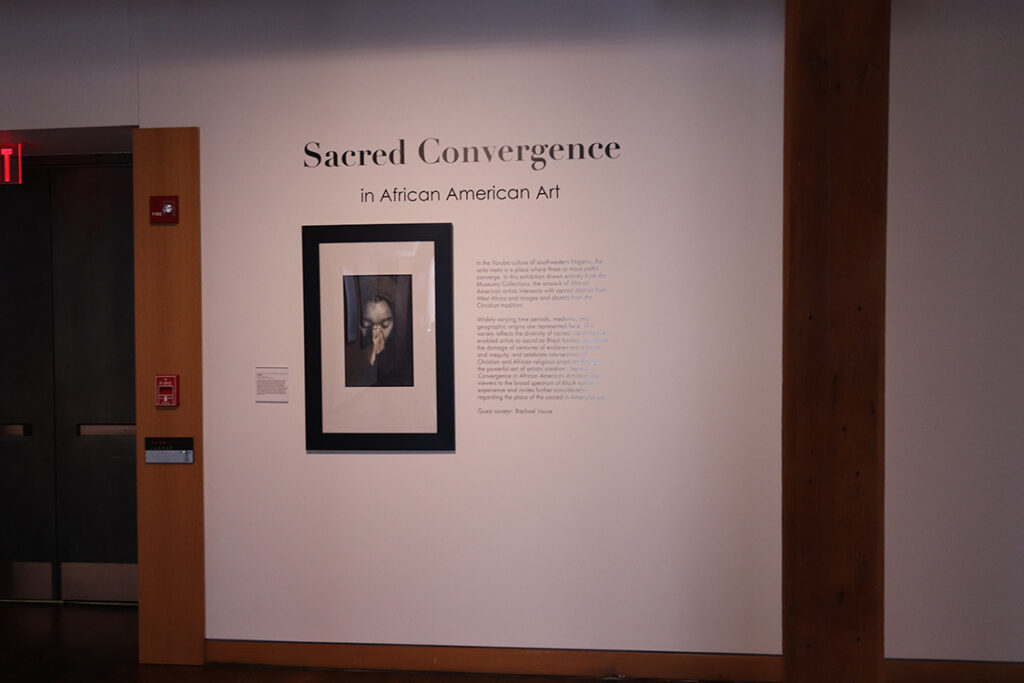

In the Yoruba culture of southwestern Nigeria, the orita meta is a place where three or more paths converge. In this exhibition drawn entirely from the Museums Collections, the artwork of African American artists intersects with sacred objects from West Africa and images and objects from the Christian tradition.

Widely varying time periods, mediums, and geographic origins are represented here. This variety reflects the diversity of sacred vision that has enabled artists to sacralize Black bodies, negotiate the damage of centuries of enslavement, erasure, and inequity, and celebrate intersections of Christian and African religious practices through the powerful act of artistic creation. Sacred Convergence in African American Art introduces viewers to the broad spectrum of Black spiritual experience and invites further consideration regarding the place of the sacred in American art.

1.

Edward L. Loper, Sr. (American, 1916-2011)

My Father, the Bishop

1975

Oil on canvas

Museums Collections, Gift of Edward L. Loper, Sr., and Janet V. Neville-Loper

Dubbed “The Prophet of Color,” Edward Loper was a beloved figure in the regional art world of Wilmington whose career culminated in paintings of kaleidoscopic brilliance. Supported by his extended family, Loper’s skill was able to grow and flourish amidst the hardships of the Great Depression and segregation. Loper was particularly close to Bishop Reese Scott, who he considered his father, despite the fact he was his stepfather. Like a figure framed in stained glass, Loper captures his father’s charismatic spirit and honors his inspirational legacy in this colorful vision.

2.

John Thomas Riddle, Jr. (American, 1933-2002)

Perfect Planning: God’s Creation

1982

Color serigraph on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

3.

Loïs Mailou Jones (American, 1905-1998)

Tribal Dancers

1996

Color silkscreen

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

4.

Jeanne Anderton (American, b. 1953)

Woman in Red Dress Touched by the Spirit, Master's Retreat, Fruitland, MD, August 1987

1987

Photograph

Museums Collections, Purchase Award, 23rd Biennial Exhibition, University of Delaware

5.

Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915-2012)

Singing Their Songs

1992

Color serigraph

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

6.

Eugene Grigsby (American, 1917-2013)

Yemenja

1997

Offset Lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

Flowing through a sea of luminous color, the Orisha (holy entity) Yemenja appears often in Grigsby’s prints. In West African Yoruba belief, Yemenja reigns over the water. The fluid dance of this maternal spirit fans out above smaller dancing figures below, her garment billowing and swirling as if to encircle and shield them. Warmer colors flicker around the figures at the bottom of the print like flames, contrasting the cooler hues above. Yemenja's role as mother to humanity may explain her legacy as a source of solace to enslaved people brought to Cuba and Brazil, a legacy passed on to their descendants in the New World.

7.

Doughba Hamilton Caranda-Martin (Liberian, b. 1974)

Untitled

2003

Gelatin silver print

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

In his young life, the onset of war impressed the horror of violence and the universality of death upon Caranda-Martin as he fled Liberia's Civil War. After moving to the United States, he utilized his art to contextualize his experience and to wrestle with the charged issues of race. The woman in this print embodies the ambiguities and the passions of these issues. Her veil may be identified with modern Liberian women or with holy women of the past; her gesture may be one of anguish or one of prayer. Caranda-Martin encourages this ambivalence in the title of the work itself. In his own words, his work acts as “a vehicle to bridge the gap of understanding between indigenous or tribal cultures and the modern world… to create images that capture the humanity and reality of emotions.”

8.

Senufo Carver (West African)

Caryatid Drum (Pinge)

20th century

Wood carving

Museums Collections, Gift of Geneva R. Steinberger

Four-legged drums are used to summon spirits, honor or commemorate individuals, and accompany initiation ceremonies of the Senufo peoples of West Africa. The Senufo encompass a group of peoples occupying a region that borders Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, and Mali.

Many drums such as this are embellished with animals associated with water spirits. A female figure supporting a drum is rare but appropriate as Senufo women uphold the matriarchal inheritance and spiritual well-being for their societies. Drums like this are played by men at a Poro initiation ceremonies for young adults, or more rarely, by women during funerals for a member of the female-only Tyekpa group.