Skills like sewing, weaving, and quilting are usually passed down through generations. The fine art schools where many of the artists in this gallery trained in painting or sculpture would have dismissed fiber arts. Yet artists turned to textiles or weaving to express a sense of community and connection. A mother’s pattern cutting or a side gig in textile design might reappear in an artist’s prints or paintings decades later. In the process, the work of these artists eases open the category of art to encompass a wider range of materials and practices.

7.

Leamon Green Jr. (United States)

Quilt Man

1999

Offset lithograph

Museums Collections, Gift of the Brandywine Workshop, Philadelphia, PA

8.

Loïs Mailou Jones (United States, 1905-1998)

African Masks

1996

Silkscreen

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

Three African masks hover above the vibrant colors of the graphic textile pattern in the background. After Loïs Mailou Jones graduated from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, she worked as a textile designer before joining the painting faculty at Howard University in Washington, D.C. The building blocks of red, blue, black, and brown in this print evoke diverse African textile traditions. Jones abstracts the woven pattern so that it is difficult to tie her work to a specific type of cloth. Throughout this exhibition, you can see how African American artists have drawn inspiration from textiles to construct visions of art beyond European practices of abstraction and representation.

9.

Romare Bearden

(United States, 1911-1988)

Pilate

1979

Lithograph

Museums Collections, Given in honor of David Driskell by Dr. Leslie Hayling, Jr

10, 11, 12.

Faith Ringgold (United States, b. 1930)

Romie We Love You (left)

Mahalia We Love You (center)

Born in the USA (right)

2012

Serigraphs

Museums Collections, Gifts of Experimental Printmaking Institute, Lafayette College

Faith Ringgold works across media in textile, painting, and printmaking. She patterned the whirling triangles and white border of these prints after windmill quilt blocks. At the center of each, she honors an important Black figure. She addresses the two artists–Romare Bearden, an artist whose work is on display to the left, and Mahalia Jackson, a skilled gospel vocalist–by name and surrounds them with words of love. The quilt blocks affirm Barack Obama’s citizenship status as the first Black president of the United States. Women in Ringgold’s family have been talented textile artists as tailors, quilters, and seamstresses for generations. Ringgold both makes quilts and uses quilt patterns in her prints and paintings.

13, 14.

Felrath Hines (United States, 1913-1993)

High Tech (top)

1991

Oil pastel

High Tech Study (bottom)

1991

Graphite, crayon

Museums Collections, Gifts of Artist’s Wife, Dorothy C. Fisher

Felrath Hines grew up watching his mother design sewing patterns for clothes. He remembers watching her draft pattern pieces on flat tissue paper that she then used to cut out fabric. When the pieces came together into a three-dimensional form, it seemed like magic. Like a sewing pattern, the graphite study for High Tech creates a plan for the final work. Light green offsets dark green and scarlet contrasts with yellow in the oil pastel, the texture recalling static on an old-school television. Subtle, asymmetrical differences between the colors bring the straight-edge geometric composition into harmony.

15.

Truman Johnson (United States, d. 2017)

Woman Weaving a Basket

1995

Graphite, white pencil

Museums Collections, Gift of Paul R. Jones

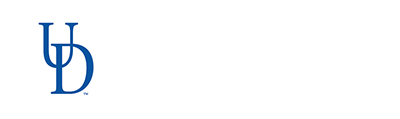

16.

Marquetta Johnson (United States)

Untitled

c. 1980

Cotton, batik, tie dye

Museums Collection, Gift of Paul R. Jones

Marquetta Johnson dyed the dynamic fabric used to make this quilt by artfully tying bundles of yardage with cord before coloring the different sections. She remixed the dyed fabric by cutting and piecing the work so that blocks of blue create interludes with strips of purple. Her mother and father taught her how to sew, but she learned how to quilt from her grandmother. Johnson is both a teacher and an artist. Through quilting within her community in Atlanta, Georgia, she shares a multi-sensory appreciation of beauty and teaches children important creative skills like sewing.

17.

Mary Pudlat (Miaji Pullat) (Nunavik, 1923-2001)

Sednas Braiding Hair

1992

Ink, crayon

Museums Collections, Gift of Frederick & Lucy S. Herman Native American Collection

Two women with tails sit on neighboring rocks, one braiding the other’s hair, their mouths open in conversation. As the goddess of the sea throughout the Arctic North, Sedna uses her flippers to navigate icy waters. Many versions of her story are told. In each, Sedna loses her fingers as punishment for some transgression. The fingers become the first seals and walruses and her own body transforms so that she can live below the waves. Inuk artist Mary Pudlat reimagines and doubles Sedna with strong, creative fingers that can once more plait braids. Braiding is a simple form of weaving. Here, the action is a powerful symbol of community and healing.

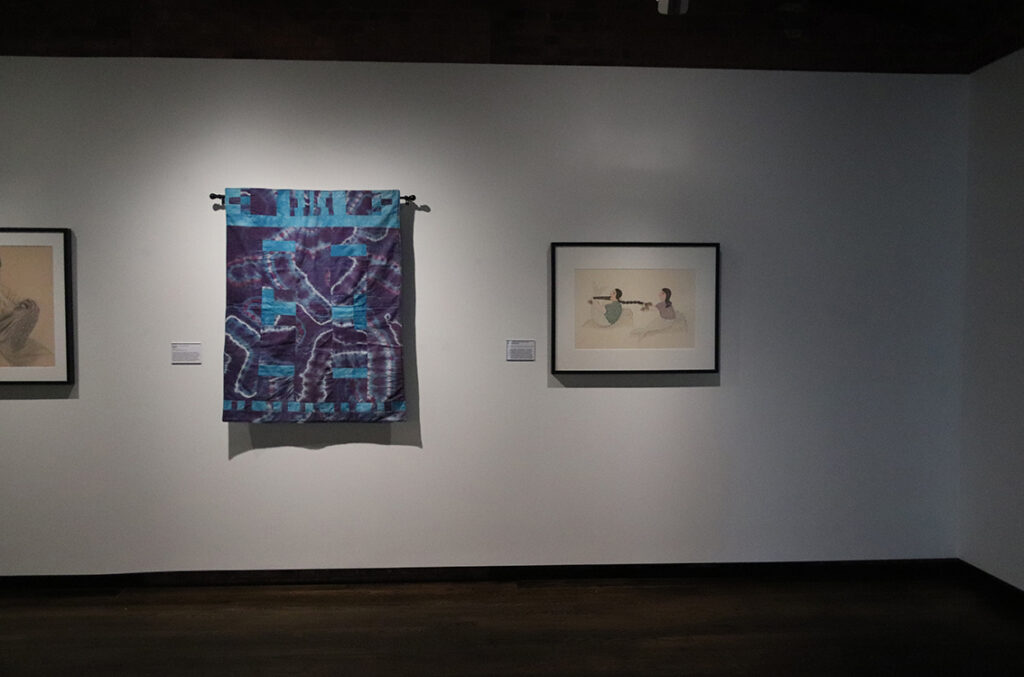

18.

Charles Edward Williams (United States)

I Sit and Sew, #1-7

2021

Oil, cotton embroidery thread on fabric with etched glass

Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Newark, Delaware; Commissioned by the Delaware Art Museum

“I sit and sew—a useless task it seems,

My hands grown tired, my head weighed down with dreams—”

Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935) begins her poem “I Sit and Sew” with a sense of frustration. A poet and activist, she was part of the first generation of Black Americans born free after the Civil War. In 2021, artist Charles Edward Williams stitched the poem, written in response to World War I, across seven nearly identical portraits of Dunbar-Nelson. Sewing can be a form of artistry, but for generations it was also “women’s work” and a symbol of oppression.

19.

Elizabeth Amos Spud (Yup’ik, 1943-2020)

Mingqaaq (Coiled Basket) (on wall to left of case)

1963

Natural and dyed grasses

Museums Collections, Gift of Mabel & Harley McKeague

20, 21.

Edna Mathlaw (Yup’ik)

Issran (Basket)

20th century

Natural grasses

Museums Collections, Gift of Mabel & Harley McKeague

Fred Tomah (Maliseet, 1951-2018)

Brown Ash Wabanaki Basket (on raised deck)

Dyed reed, ash handle

Museums Collections, Gift of Leslie & Virginia Tronzo

Only when woven together do grasses and reeds become strong enough to support heavy loads. Yup’ik artist Edna Mathlaw dried and twined sea grass to shape the open-weave of this issran (basket). Elizabeth Amos Spud, also Yup’ik, dyed and coiled the same grass to form a pattern of butterflies in the basket that hangs on the wall. The same material, treated differently, takes on immensely different properties. Maliseet artist Fred Tomah used ash to weave his basket, which is much stiffer and more unyielding than grass. Its greater resistance informs the wider, straighter weave of his basket. Each of these artforms has a deep history, materially tying the artists’ communities to the land where the artists gathered their bundles of grass and ash splints.