In 1854, U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas, a Democrat from Illinois, wrote and managed passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820. On the principle of “popular sovereignty,” Douglas argued that allowing Western territory settlers to self-determine admission of slaves would promote national expansion and alleviate regional tensions over slavery.

Instead, the slavery crisis escalated to threaten national unity, especially with the 1857 Dred Scott decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which determined that Blacks could never be citizens and that slavery could be constitutionally expanded anywhere.

Popular sovereignty, the Dred Scott decision, the expansion of slavery, and equal rights for blacks drove political debates in the years leading up to the 1860 election. Democrats used fear of equal rights for Blacks against the recently formed Republican Party, which, with its mix of anti-slavers and abolitionists, still largely preferred to ignore the question of equality.

Other sectional issues pitted the North against the South. The North believed tariffs benefited manufacturing; the South wanted low tariffs to support agricultural trade. Westerners favored internal improvements to rivers, railways, telegraphs, and the mail; Northerners supported free land for settlers through the Homestead Bill; white Southerners saw the western expansion and free labor as a competition for slavery.

Although he had been defeated in 1858 by Stephen Douglas in his bid to represent Illinois in the U.S. Senate, Abraham Lincoln was actively publishing and speaking about these issues, attracting the attention of Republican Party leaders in the years leading up to the 1860 election.

Maurer, Louis. The Great Republican Reform Party, calling on their candidate. New York:

for sale by [Nathaniel Currier] at no. 2 Spruce Street, [1856]. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection

Former Senator John C. Frémont of California, depicted at the far right of the cartoon shown above, was the founder and first nominee of the Republican Party in the presidential campaign of 1856. A “motley array of radicals and reformers” supported the Republican ticket (left to right): a temperance advocate, a cigar-smoking and trousered suffragette, a ragged socialist holding a liquor bottle, a spinsterish libertarian, a Catholic priest holding a cross, and a free black dandy. Responding to his constituents, Frémont’s bubble ends “... above all the Equality of our Colored brethren, shall be maintained ...”

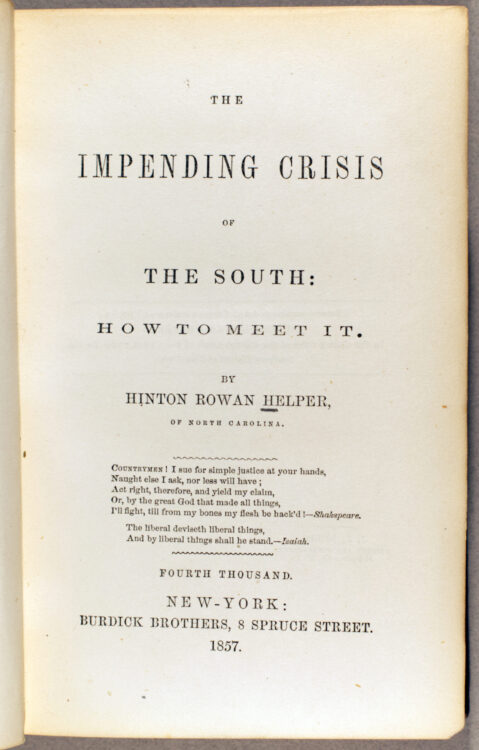

Helper, Hinton Rowan. The Impending crisis of the South: how to meet it. New York: Burdick Bros., 1857. “Fourth thousand.” Distribution offer by E.M. Davis mounted on front free endpaper.

Helper was a white non-slaveholder from North Carolina who railed against slavery in this influential and widely distributed book, first published in 1857. His position was that the economics of slavery disadvantaged non-slaveholders like himself, and he used information from the 1850 census to compare rural Southern statistics with more prosperous Northern industrial data. He called slavery a “moral, social, civil, and political evil,” a threat to national greatness. Southern Democrats accused Helper of fostering class warfare and Northern Republicans championed the reasoning of his anti-slavery message.

E.M. Davis, assumedly a Republican activist in Philadelphia, purchased 500 copies of The Impending Crisis for free distribution to individuals, libraries, lyceums, and reading rooms to promote Helper’s message that slavery was driving “the impending crisis” between the South and the North.

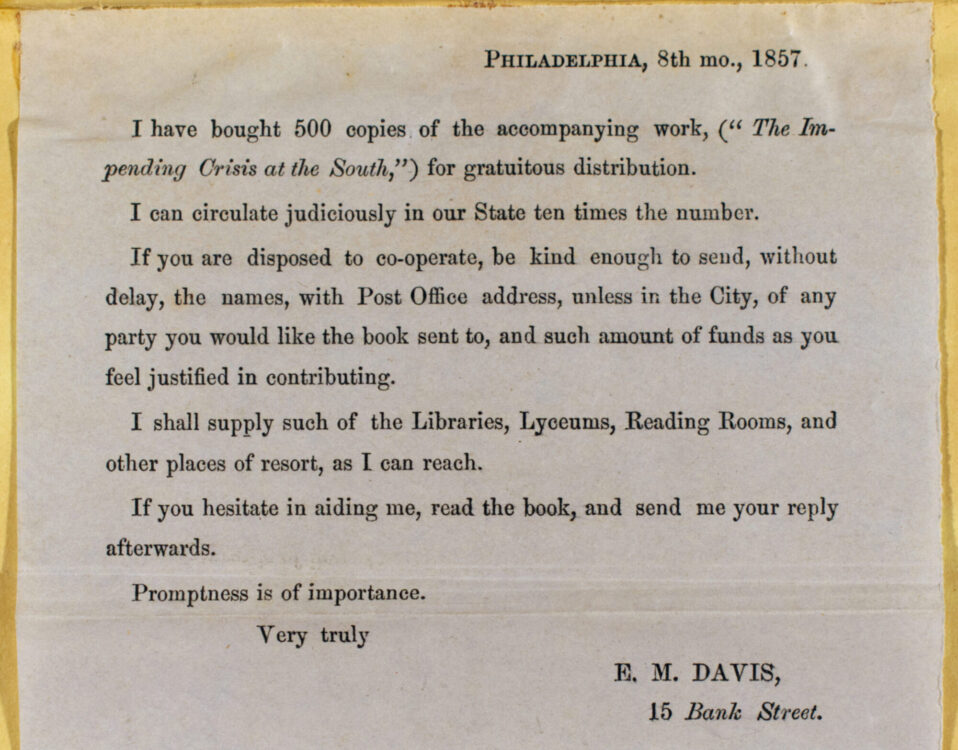

Nast, Thomas. Albumen photograph of Nast’s caricature of Horace Greeley, editor of the New-York Tribune. New York: E. and H.T. Anthony, 1866. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection

Political activist Horace Greeley (1811-1872) founded the New-York Tribune in 1841. Fiercely abolitionist and reform-minded, Greeley’s paper and other publications of the Tribune Association championed equal rights for freedmen and opportunities for Americans through expansion in the Western territories. As shown on the verso of this carte-de-visite, the source for Thomas Nast’s caricature was a photographic negative from Matthew Brady’s National Portrait Gallery. Next to Greeley is an issue of his newspaper transformed into a black face.

The extent and significance of Greeley’s local and national reach through his newspaper and other publications cannot be overstated. He was a major voice for the emerging Republican Party leading up to 1860.

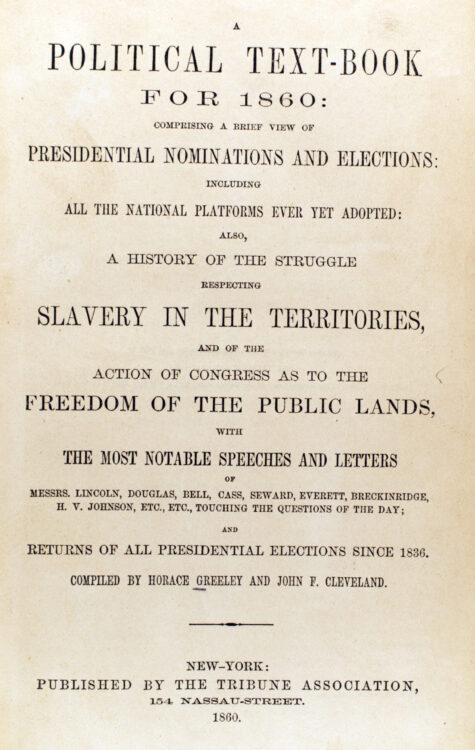

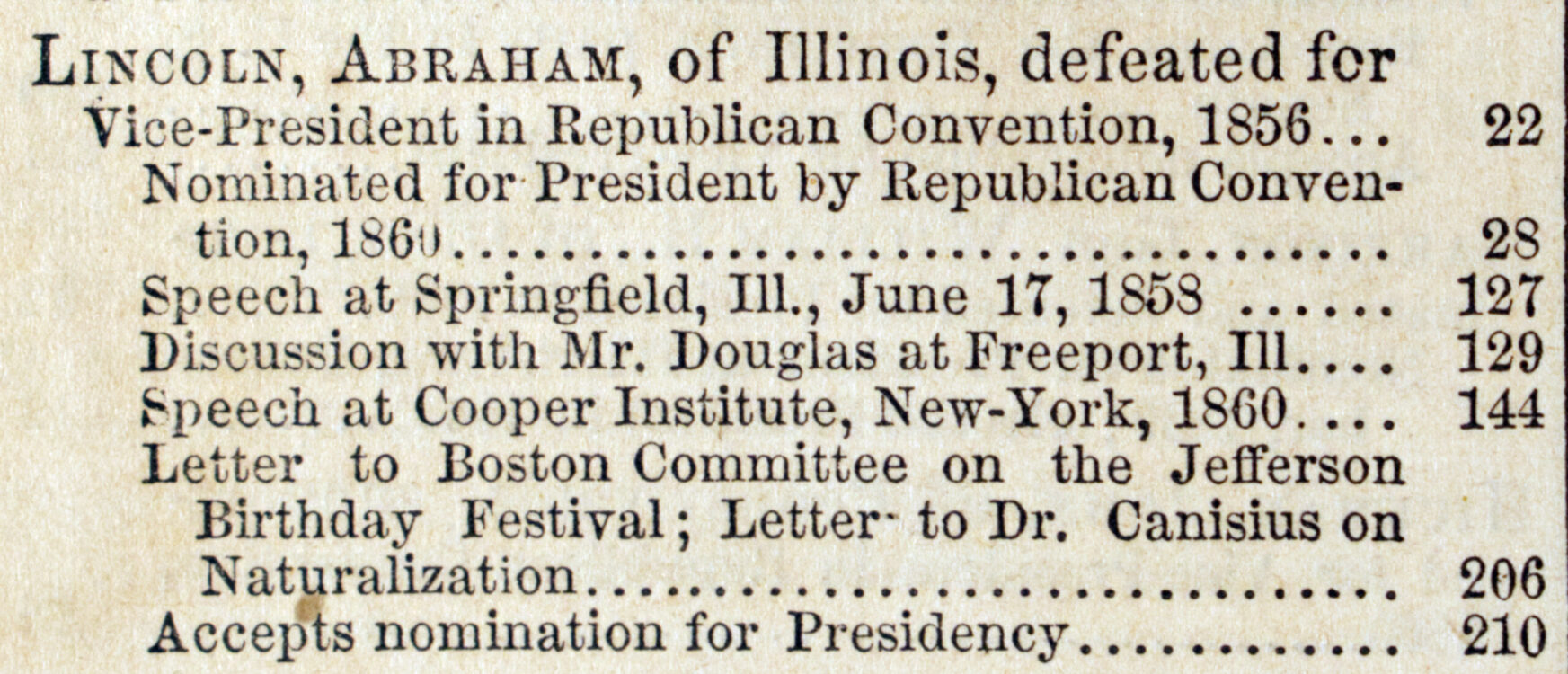

Greeley, Horace, and John F. (John Fitch) Cleveland. A Political text-book for 1860: comprising a brief view of presidential nominations and elections, including all the national platforms ever yet adopted, also, a history of the struggle respecting slavery in the territories, and of the action of Congress as to the freedom of the public lands, with the most notable speeches and letters of Messrs. Lincoln, Douglas, Bell, Cass, Seward, Everett, Breckinridge, H.V. Johnson, Etc., Etc., touching the questions of the day, and returns of all presidential elections since 1836. New York: Tribune Association, 1860.

Founder and editor of the New-York Tribune, Horace Greeley was a staunch voice against the spread of slavery into the Western territories, which was a major issue for Republicans in 1860. He published this political textbook with an historical overview of the Party’s platform along with notable speeches and letters from the party leaders.

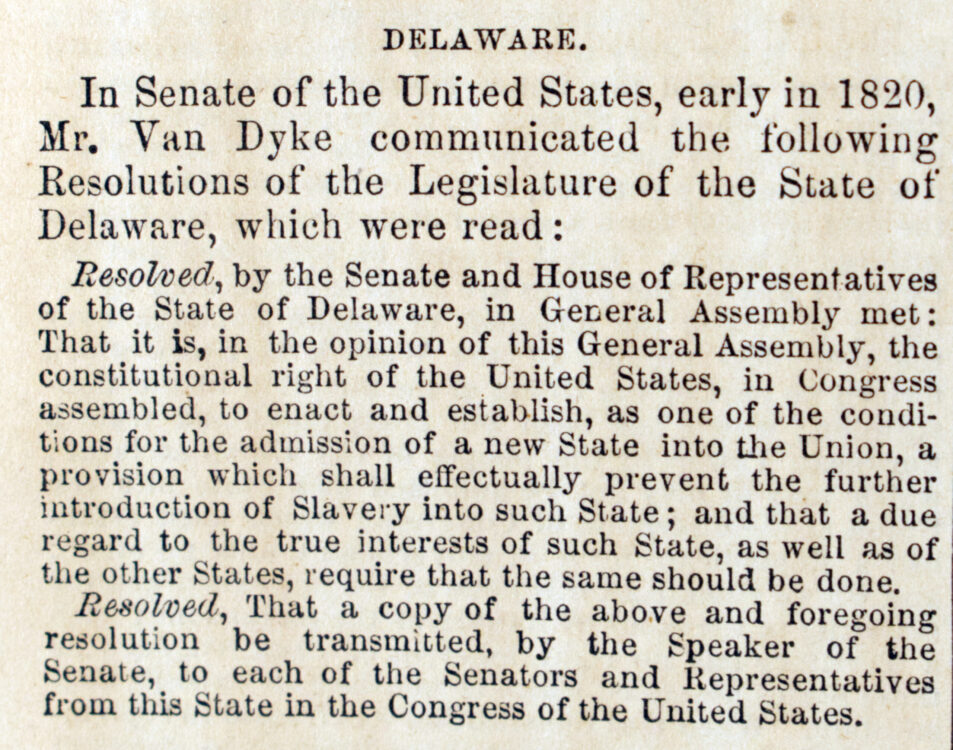

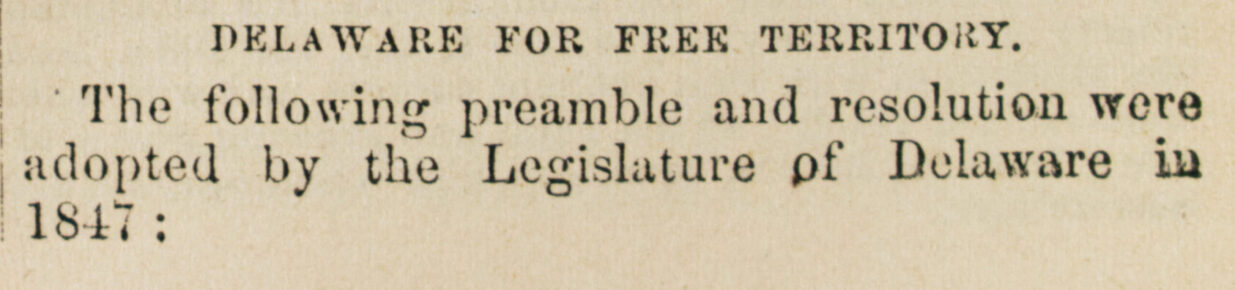

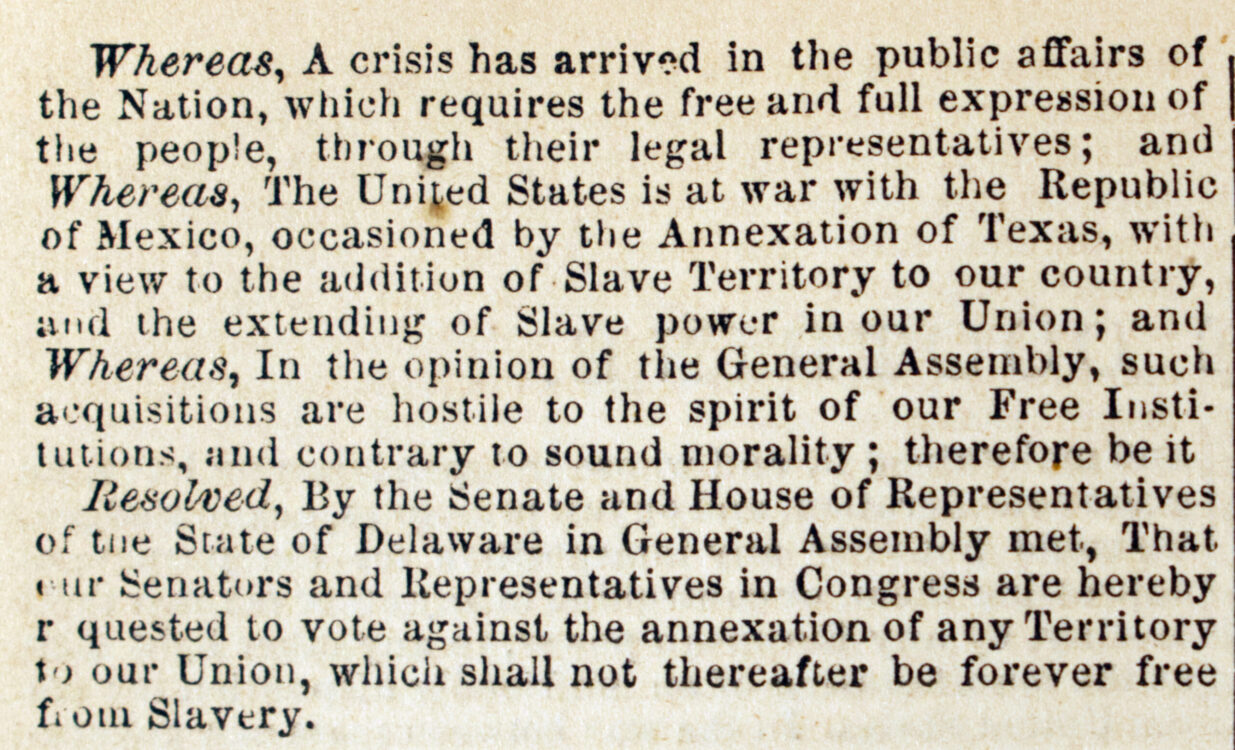

Greeley’s historical overview included 1820 and 1847 resolutions of the Delaware Assembly against the extension of slavery into territories as a condition of admission as a new state in the Union, as slavery was “hostile to the spirit of our Free Institutions and contrary to sound morality.” The reality was that Delaware was a border state in 1860, with 91.7% of its black population free and 1.6% of its total population still enslaved.

The index entry for Lincoln in the Political text-book for 1860 includes two of his speeches that became important for the Republican campaign: his 1858 “Springfield speech,” which addressed the Nebraska Doctrine and the Dred Scott decision, and his 1860 speech at the Cooper Union.

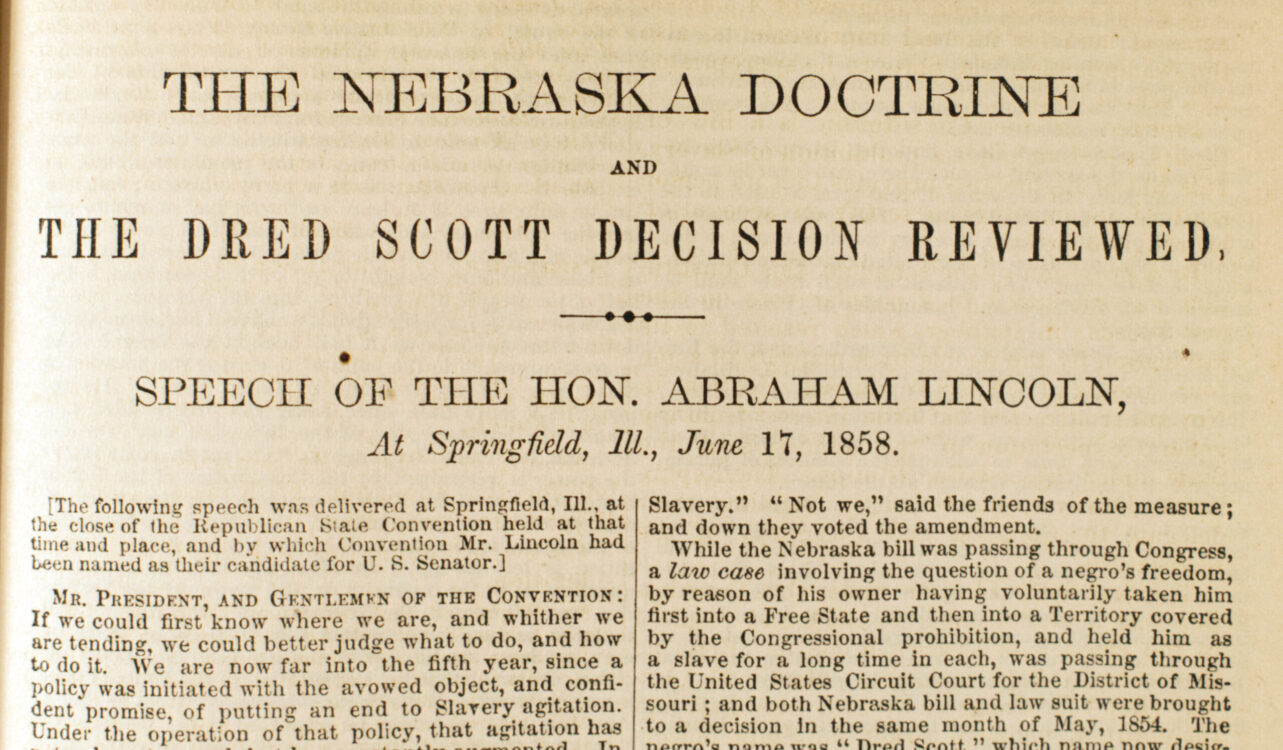

Lincoln’s “House Divided” Springfield speech was delivered at the close of the Illinois Republican State Convention in June 1858 when he was nominated as their candidate for U.S. Senator. Though he lost the senatorial race to Stephen Douglas, Lincoln’s speeches and debates from that campaign were recirculated by Republicans in 1860. The Springfield speech summarized the national crisis: the strong moral and political convictions of both opponents and advocates of slavery put the nation in an unsustainable impasse. National unity was threatened.

Lincoln, Abraham. The Republican Party vindicated--the demands of the South explained. Speech of Hon. Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, at the Cooper Institute, New York City, February 27, 1860. [Washington, D.C.?: publisher not identified], 1860.

In February 1860, Lincoln delivered a speech at the Cooper Institute (later known as the Cooper Union) at the invitation of the Young Men’s Central Republican Union. Choosing his topic to validate the Republican anti-slavery platform, Lincoln’s momentous address at the Cooper Union had critical impact on his national visibility.

Responding to a remark from one of Senator Douglas’s 1859 speeches, Lincoln posed and answered a question in his address: “Does the proper division of local from federal authority, or anything in the Constitution, forbid our Federal Government to control as to slavery in our Federal Territories?” After exhaustive reading and research in the Springfield libraries, Lincoln used historical facts and legal precedent, an ironic appeal to “the South,” and an inspirational call at the end of his speech to have political faith that “right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.” The speech gives great insight into Lincoln’s legal prowess, his ability to humor a crowd, and his ability to inspire support for a morally just position.

![Maurer, Louis. The Great Republican Reform Party, calling on their candidate. New York: for sale by [Nathaniel Currier] at no. 2 Spruce Street, [1856]. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection. Image courtesy Library of Congress. Maurer, Louis. The Great Republican Reform Party, calling on their candidate. New York: for sale by [Nathaniel Currier] at no. 2 Spruce Street, [1856]. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection. Image courtesy Library of Congress.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/the-rail-splitter-surprise/wp-content/uploads/sites/289/2024/06/LOC-Great-Republican-Reform-Party.jpg)

![Publishing credits on the verso of albumen carte de visite of Horace Greeley. New York: E. and H.T. Anthony, [1866]. Publishing credits on the verso of albumen carte de visite of Horace Greeley. New York: E. and H.T. Anthony, [1866].](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/the-rail-splitter-surprise/wp-content/uploads/sites/289/2024/08/Greeley-albumen-002-e1722971667542.jpg)

![Scripps, J. L. (John Locke). Life of Abraham Lincoln. New York: [Horace Greeley], 1860. Publisher’s advertisement for The New York Tribune. Scripps, J. L. (John Locke). Life of Abraham Lincoln. New York: [Horace Greeley], 1860. Publisher’s advertisement for The New York Tribune.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/the-rail-splitter-surprise/wp-content/uploads/sites/289/2024/06/Scripps-Tribune-ad-001-e1724275064275.jpg)

![Lincoln, Abraham. The Republican Party vindicated –: the demands of the South explained. Washington, D.C.?: [publisher not identified], 1860. Lincoln, Abraham. The Republican Party vindicated –: the demands of the South explained. Washington, D.C.?: [publisher not identified], 1860.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/the-rail-splitter-surprise/wp-content/uploads/sites/289/2024/06/Cooper-Union001-scaled-e1719081716455.jpg)