The flavor of the 1860 presidential campaign is preserved through the political tracts, political cartoons, campaign songs, contemporary reports of the political conventions, and personal accounts of those who participated.

The 19th-century public and voters (mostly white men) appear to have been well-informed, or at least to have had ready access to party platforms and candidate profiles through the national press, popular magazines such as Harper’s or Leslie’s Illustrated, and speeches and publications sold by the executive congressional party committees.

The public also consumed campaign ephemera, song sheets, Currier & Ives prints, portraits of candidates, and political cartoon prints, many of which reflect the rampant cultural racism of the era, regardless of where the material was published.

Maurer, Louis. “ ‘The N.....’ in the woodpile.” [New York: Currier and Ives] 1860. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection. Digital image courtesy of the Library of Congress

Here, Maurer parodies the Republican efforts to downplay their antislavery platform, with Tribune editor Horace Greeley assuring “Young American,” “we have no connection with the Abolition Party, but our Platform is composed entirely of rails, split by our Candidate.” Newly elected candidate Lincoln sits atop the “Republican Platform” of split rails, through which peeps a grinning Black man.

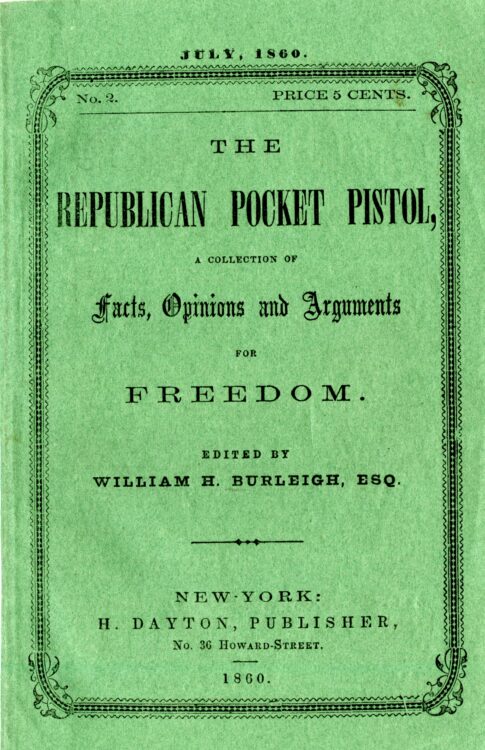

Dayton, Hiram. The Republican pocket pistol: a collection of facts, opinions and arguments for freedom. No. 2, July 1860. Edited by William Henry Burleigh. New York: H. Dayton, publisher, no. 36 Howard-Street, 1860.

This pocket-sized campaign fact book suggests that a voter would have carried this tome for ready access to political information about his party and candidate.

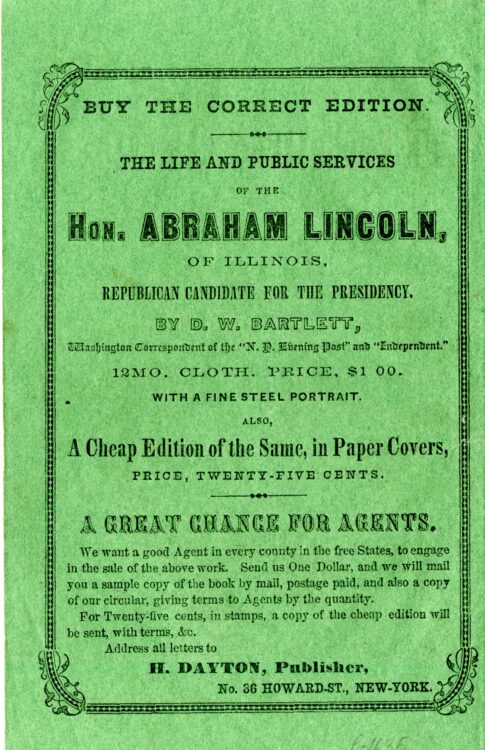

Scroggs, Gustavus Adolphus., et al. The Duty of Americans: speeches of Gen. G.A. Scroggs (president of the American State Council), Dr. S.B. Hunt, and E. Carlton Sprague, Esq., at the American meeting held at Aurora, Erie Co., N.Y., Aug. 4, 1860; and of Hon. Geo. R. Babcock, on taking the chair at the Lincoln Mass Meeting, held at Buffalo, Aug. 4, 1860; also, a letter from Hon. James O. Putnam, together with articles from the Commercial Advertiser on the pending election. Buffalo, New York: Office of the Buffalo Patriot and Journal, 1860.

By the summer of 1860, the campaign was in full swing with mass meetings and rallies where party loyalists could speak on behalf of their candidates. The Buffalo Patriot and Journal compiled this campaign literature with two speeches and a published letter of note.

Sic Semper. [Song] by a Virginian. Place and publisher unknown, [after 1861]. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection

From context, this undated Southern ribbing can be dated to some time after Lincoln’s inauguration, as it cites members of his cabinet: Chase, Cameron, Blair, Bates, Smith, and “Wildcat” Seward, several of whom had been his rivals for the Republican Party nomination. The Virginian echoes the 1860 campaign rhetoric, noting Lincoln’s weighty axe used to split rails (leading to Southern secession) and calling his administration “Black” [Republicans].

In a somber twist of fate, “Sic Semper Tyrannis,” Virginia’s state motto, were the words yelled by John Wilkes Booth when he leapt to the stage in Ford’s Theatre after assassinating President Lincoln in 1865.

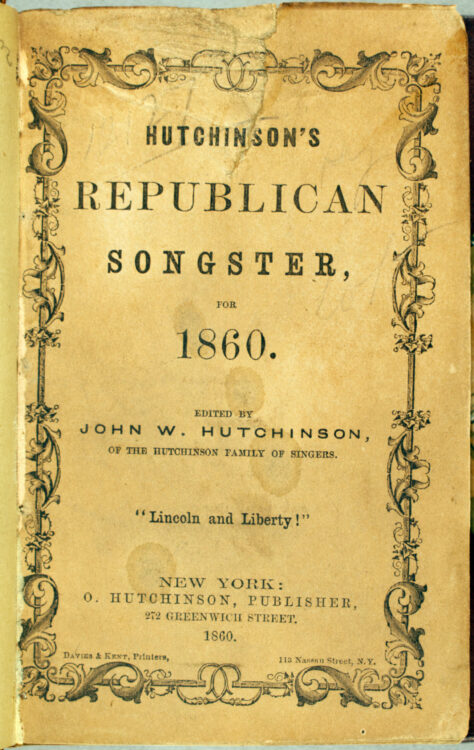

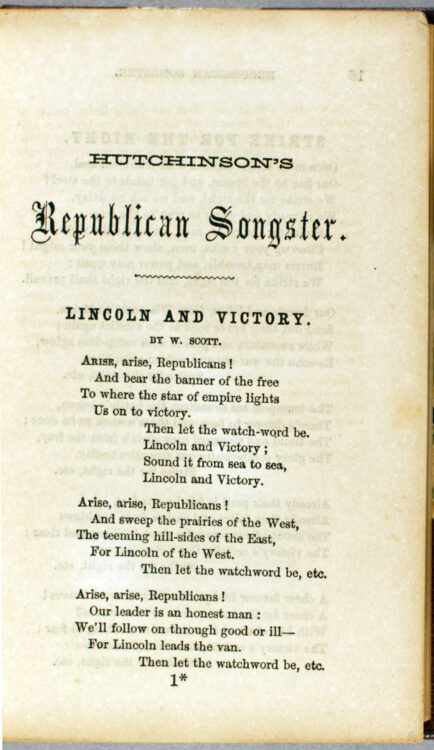

Hutchinson, John W. (John Wallace), and George W. (George Washington) Bungay. Hutchinson’s Republican songster, for the campaign of 1860. New York: O. Hutchinson, publisher, 67 Nassau Street, 1860.

Singing in four-part harmony, the Hutchinson Family Singers were popular entertainers in the mid-19th century. Based in Lynn, Massachusetts, they began touring the country in 1840 and built a catalog of political, social, comic, sentimental, and dramatic works. They took up abolitionism, temperance, and women’s rights, and toured for much of 1845 in England with Frederick Douglass.

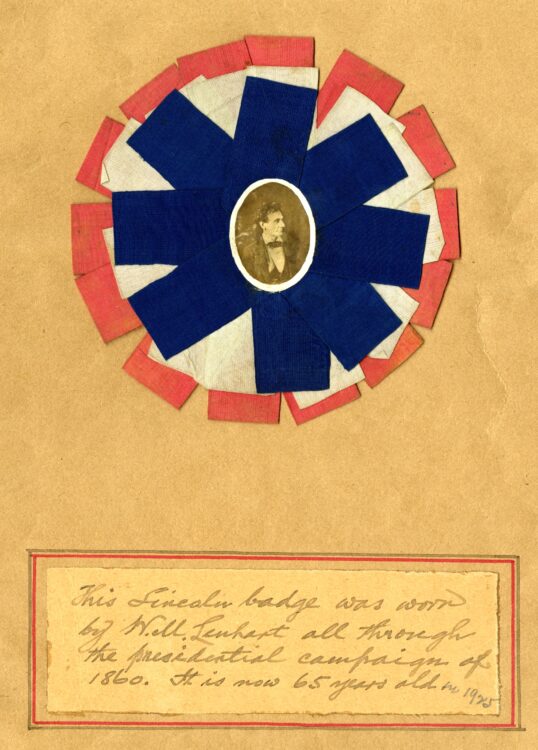

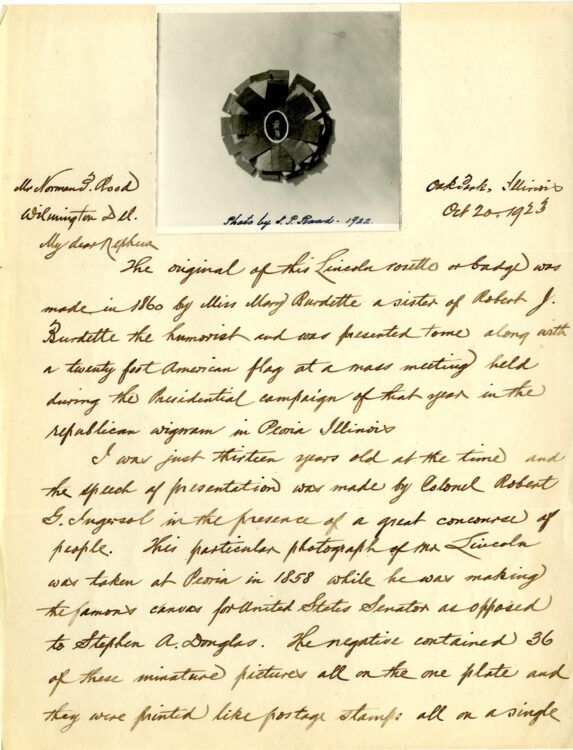

Lincoln presidential campaign rosette worn by Walter M. Lenhart, 1860, with autograph letter with attached photograph, Walter M. Lenhart, Oak Park, Illinois, to Norman P. Rood, Wilmington, Delaware, October 23, 1923. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection

Norman P. Rood (1876-1964), president of the Independent Powder Company of Joplin, Missouri, moved to Wilmington when his company was acquired by Hercules Powder Company in 1914, rising from manager of Industrial Research to vice president of the company.

Rood’s Uncle Walter Martin Lenhart (1847-1928) presented this souvenir of the 1860 presidential campaign to Rood, who in turn presented the item with its letter of provenance to the noted Lincoln collector, Frank G. Tallman, Jr. (1894-1952). Tallman’s collection is the core of the Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln Collection, from which almost all items featured in this exhibition are drawn.

Lenhart provided a full account of his Lincoln treasure: he was 13 years old, living in Peoria, Illinois, at the time of the 1860 campaign. Mary G. Burdette (1842-1907), a Baptist teacher and sister of the humorist Robert J. Burdette (1844-1914), made the campaign ribbon rosette and presented it, along with a 20-foot American flag, to the boy on occasion of a mass meeting at the Republican wigwam in Peoria. Agnostic orator and abolitionist Robert J. Ingersoll (1833-1899) was the featured speaker at the convention before a “great concourse of people.”

Lenhart described the source of the Lincoln photograph at the heart of the rosette. The photograph was taken in Peoria when Lincoln was canvassing for the Senate seat against Stephen Douglas. “The negative contained 36 of these miniature pictures all on the one plate and they were printed like postage stamps all on a single sheet.”

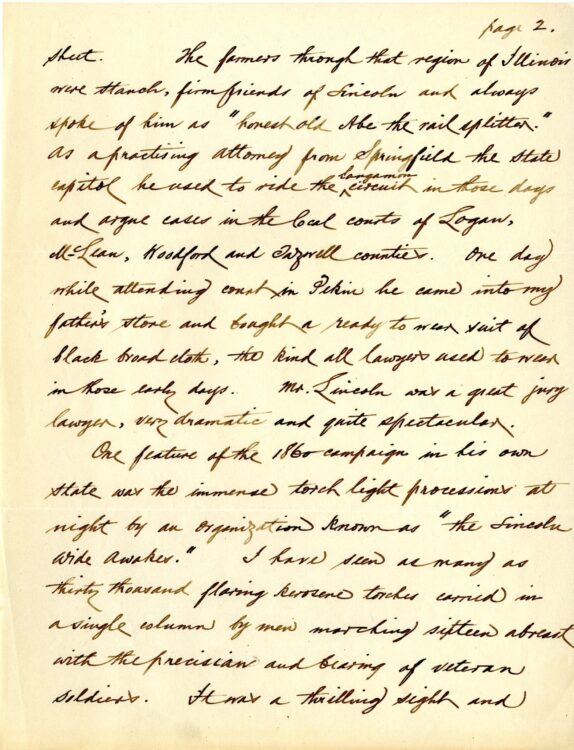

Lenhart recalled that regional farmers were firm friends of Lincoln and spoke of him as “honest old Abe the rail splitter.” Lenhart also recalled that Lincoln once purchased “a ready to wear suit of black broadcloth, the kind all lawyers used to wear” at his father’s store in Pekin.

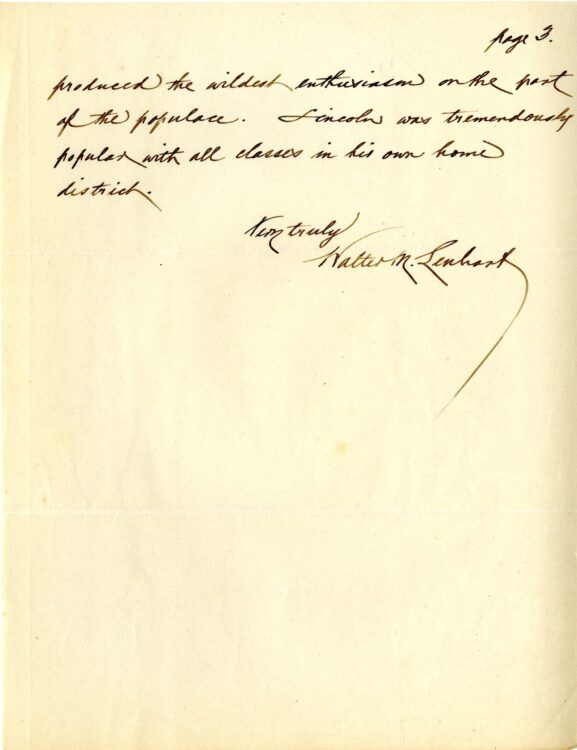

Lenhart shared another vivid recollection of the 1860 campaign: “the immense torch light processions at night by the organization known as ‘the Lincoln Wide Awakes.’ I have seen as many as thirty thousand flaring kerosene torches carried in a single column by men marching sixteen abreast with the precision and bearing of veteran soldiers. It was a thrilling sight and produced the wildest enthusiasm on the part of the populace.”

Oldroyd, Osborn H. (Osborn Hamiline). Lincoln’s campaign; or, the political revolution of 1860. Chicago: Laird and Lee, 1896.

Wide-Awake Lincoln clubs originated with a semi-military organization that escorted Cassius M. Clay, of Kentucky, to the speaker’s platform at a gubernatorial event in Hartford, Connecticut, in the Spring of 1860. The young men carried swinging oil lamps attached to a rail and wore capes and caps to protect themselves from the dripping fuel. Making quite an impression, Wide-Awake clubs sprang up throughout the campaign.

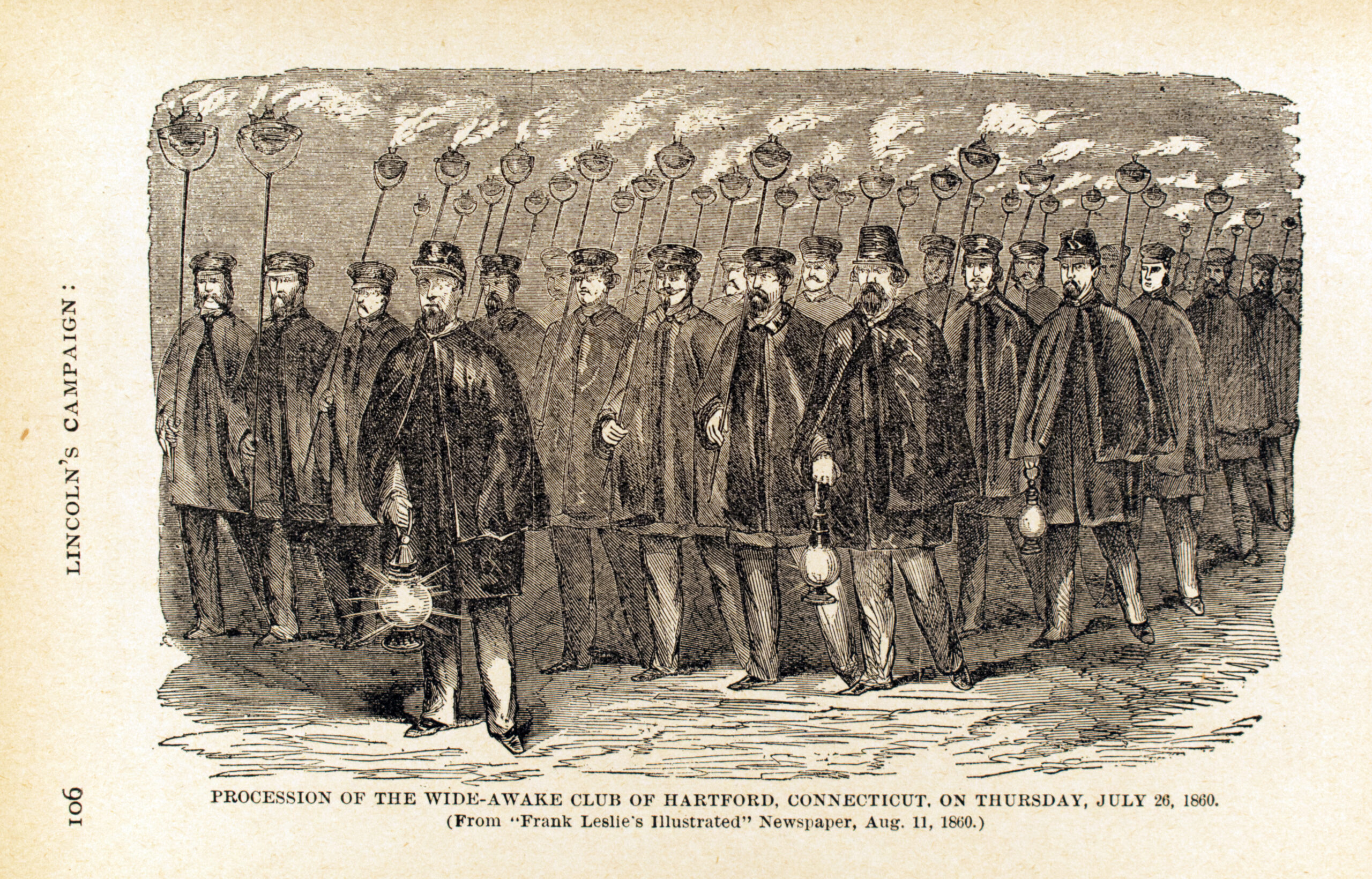

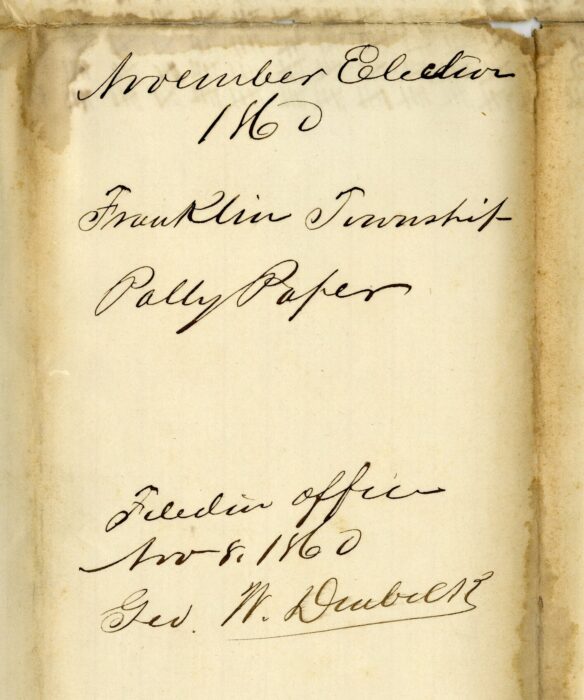

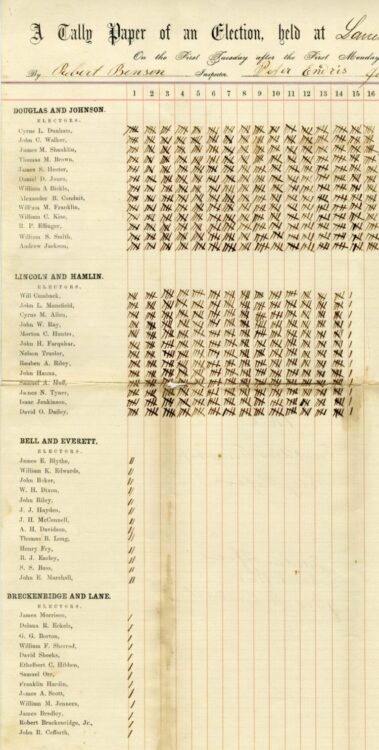

November election 1860. Franklin Township tally paper filed in office November 8, 1860, George W. Denbo. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection

Tally paper of an election, held at Lanesville in Franklin Township, Harrison County and State of Indiana, on the First Tuesday after the First Monday in November, 1860, for the election of thirteen presidential electors for the state of Indiana. By Robert Benson, inspector; Peter Endris, John L. Ham, judges; John E. Williams, James H. Green, clerks. (Verso of November election 1860. Franklin Township tally paper filed in office November 8, 1860, George W. Denbo.) MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection

The presidential election of 1860 was split four ways: Stephen Douglas and Herschel V. Johnson (Democratic Party); Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin (Republican Party); John Bell and Edward Everett (Constitutional Union Party); and John C. Breckinridge and Joseph Lane (Southern Democratic Party).

In the Electoral College system, Indiana was apportioned 13 electors. Each party named its slate of 13 electors, who were then committed to casting votes representing their party’s nominees.

Of the 52 electors listed on this tally sheet, only the 13 who represented the winning party at the state level participated in the Electoral College vote.

Douglas and Johnson – 241

Lincoln and Hamlin – 71

Bell and Everett - 2

Breckinridge and Lane - 1

In Franklin Township, Douglas and the Democratic Party led the other candidates, but Lincoln carried the state of Indiana through other voting districts and won its 13 electoral votes.

Nationally, Lincoln won both the popular and electoral vote in 1860, with just under 40% of the popular vote, totaling 1,865,908 and 180 electoral votes. Delaware cast its 3 electoral votes for the Southern Democratic ticket of Breckinridge and Lane, who placed second with 72 electoral votes.

Lincoln and Hamlin - 180

Breckinridge and Lane - 72

Bell and Everett - 39

Douglas and Johnson - 12

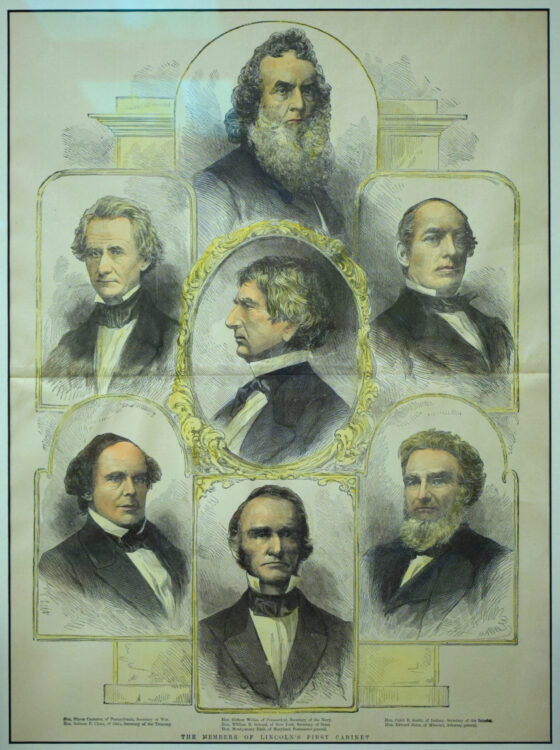

“The Members of Lincoln’s First Cabinet” in The Soldier in Our Civil War: A Pictorial History of the Conflict, 1861-1865, New York: J. H. Brown, 1884. Gift of the Hon. William L. Witham, Jr.

After the election of 1860, Lincoln formed his first cabinet. An interesting measure of the man and his political savviness is that Lincoln invited several of his former rivals for the Republican nomination to join the cabinet: Seward, Bates, and Chase.

This print is from The Soldier in Our Civil War: A Pictorial History of the Conflict, 1861-1865, which was published in 1884. This title is fairly scarce today, perhaps because double-page illustrations such as this one were removed from the volume for display. The University of Delaware does not have a copy, but it does own what is known as a “salesman’s dummy,” a prospectus used to show potential customers what the book would look like, with choices of bindings and paper quality. The UD dummy includes the print, which is a double-page spread from a book with a height of 42 cm (approximately 16.5 inches). This print is a gift of Judge Witham, a former president of the Lincoln Club of Delaware.

Shown top to bottom, left column to right, cabinet positions: Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania, War; Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, Treasury; Giddeon Welles of Connecticut, Navy; William H. Seward of New York, State; Montgomery Blair of Maryland, Postmaster General; Caleb B. Smith of Indiana, Interior; Edward Bates of Missouri, Attorney General.

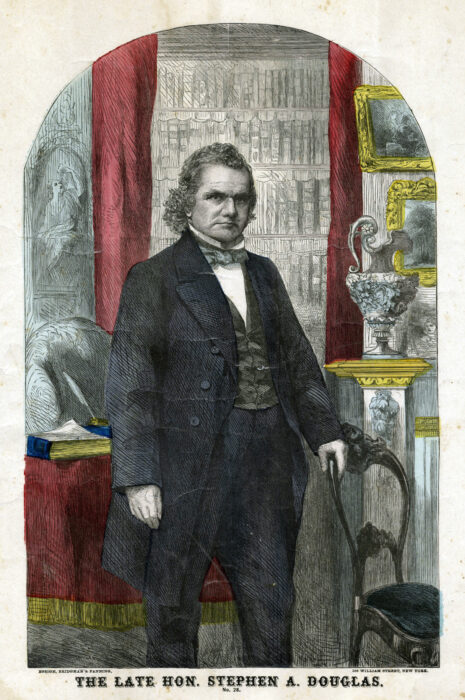

The late Hon. Stephen A. Douglas. New York: Ensign, Bridgman and Fanning, 1861. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection

A further testament to the significance of Lincoln’s presidential election in 1860 is the fact that even Stephen Douglas, his former adversary in state and national elections, came around to support Lincoln’s dedication to preservation of the Union. Douglas’s sobriquet, “the Little Giant,” reflects his stature, as depicted in this broadside published shortly after his death, but also his political clout.

Despite their famous debates of 1858, Douglas was at Lincoln’s side, holding his stovepipe hat, at the inauguration on March 4, 1861. Douglas held two hours of private counsel with the President two days after the fall of Fort Sumter on April 12. Thereafter, he issued a statement to the press, that “he was prepared to sustain the President in the exercise of all his constitutional functions to preserve the Union, and maintain the government, and defend the Federal Capital.”

In a speech to the Legislature of Illinois on April 25, Douglas declared, “Now permit me to say to the assembled Representatives and Senators of our beloved State, composed of men of both political parties, in my opinion it is your duty to lay aside, for the time being, your party creeds and party platforms...” He continued, “… forget that you were ever divided, until you have rescued the government and the country from their assailants.”

The strenuous presidential campaign of 1860 and his speaking engagements to support the Union in 1861 weakened Senator Douglas. He died on June 3, 1861, in a hotel room in Chicago.

Committed to his Party's platform of anti-slavery and preservation of the Union, President Abraham Lincoln led on through the great crisis of the Civil War. He was elected to a second term in 1864 but died on April 15, 1865, not long after his inauguration in March and the South's surrender on April 9.

![Maurer, Louis. “The N—–” in the woodpile. [New York: Currier and Ives] 1860. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection. Image courtesy Library of Congress. Maurer, Louis. “The N—–” in the woodpile. [New York: Currier and Ives] 1860. MSS 0521 Lincoln Club of Delaware Abraham Lincoln collection. Image courtesy Library of Congress.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/the-rail-splitter-surprise/wp-content/uploads/sites/289/2024/06/LOC-Woodpile.jpg)

![Sic Semper. [Song] by a Virginian. Place and publisher unknown, [1860]. Sic Semper. [Song] by a Virginian. Place and publisher unknown, [1860].](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/the-rail-splitter-surprise/wp-content/uploads/sites/289/2024/06/sic-semper-001-e1719153259798.jpg)