Animal

Pliny’s Natural History was a Roman encyclopedia, composed circa 77-79 CE, that sought to present the whole knowledge of natural science. Pliny was employed as an imperial administrator and wrote the work in his spare time. He acted primarily as a compiler, gathering information from hundreds of Greek and Roman sources. The factual accuracy and scientific value of the Natural History is limited at best, as Pliny tended to be overly credulous of his sources, and thus accepted a great deal of hearsay, exaggeration, and superstition. Still, the work was immensely popular in its day, and thus provides a valuable compendium of what was believed about the natural world in Roman times. It also went on to serve as a foundational text for many European natural histories. It circulated widely in manuscript in the Middle Ages, and was first printed in 1469. However, Pliny’s reliability was in doubt by the end of fifteenth century: European medical scholars cited inaccuracies in his sections on medicinal plants, but these were initially blamed on errors made by scribes who had inaccurately copied Pliny’s text. His authority gradually ebbed over the course of the sixteenth century, as scholars shifted away from the presumed knowledge of the ancients, in favor of direct observation and empirical evidence.

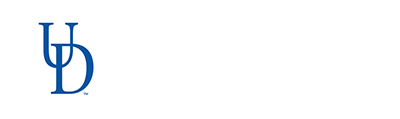

The volume shown here is the fourth printing of Cristoforo Landino’s (1424-1504) Italian translation. First published in 1476, Landino’s edition was the first time that Pliny’s work had ever appeared in the vernacular. Seen here is an illustration of a sea serpent. Pliny wrote that the Indian Ocean in particular was home to a great variety of monsters, including three acre whales, 150 foot sharks, and 300 foot eels. These creatures were said to be most plentiful during the solstices, when storms would drive them up from the depths where they normally lived.

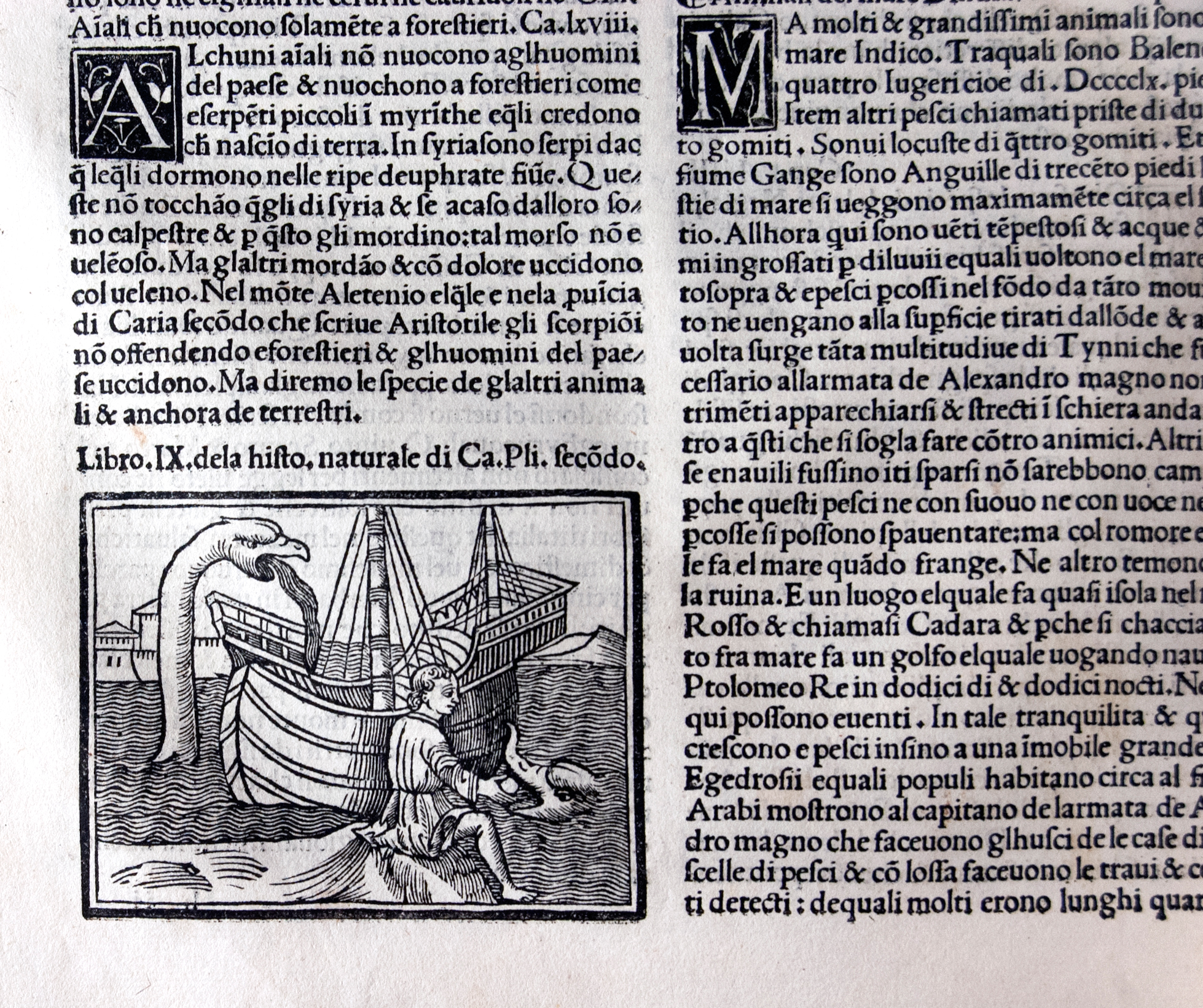

The Hortus Sanitatis was a popular medieval encyclopedia of natural history, with sections covering plants, animals, birds, fish, stones, and the pathological indications of bodily fluids. The book focused on the medicinal uses of the natural world, although, keeping with a tradition of earlier bestiaries, it included a great deal of anecdotal information and stories as well. Much of the herbal knowledge printed in the Hortus derived from the 1485 Gart der Gesundheit, while the sections on zoology descended from medieval bestiaries. In compiling these sources, the Hortus served to use the relatively new printing press to gather together in one place a great deal of information that had previously been available only in disparate manuscripts scattered across Europe. The first printing appeared in 1491, and, in testament to its popularity, the Hortus went through at least forty-two editions between then and 1550. (The sixth edition is shown here).

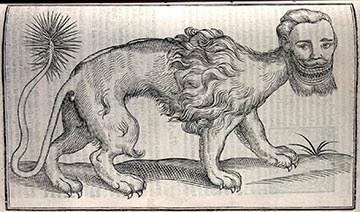

The section on animals provides an especially interesting window onto medieval conceptions of zoology. Animals are classified based on whether they live on land, air, or sea. Many recognizable animals appear, and the coverage spans as far as Africa and India. But because its compilers relied on written authority over direct experience, the Hortus also includes a great number of animals that no one had ever seen, and that no one ever would see. Amongst the ranks of the animal kingdom one finds, here, such oddities as dog-men, dragons, human-headed serpents, Leviathan, manticores, gryphons, harpies, unicorns, and aquatic lions. Other times, what appears to be a fantasy is actually just a very wildly inaccurate drawing: a crocodile is shown with the head of a pig, and a whale, though described accurately, appears as a mermaid. A unicorn is shown here, alongside vipers, bears, and an ox, which is in the act of goring a knight.

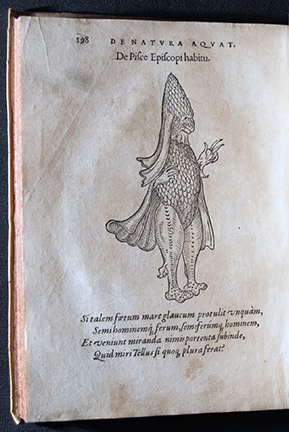

De Natura Aquatilium Carmen is a pictorial natural history, with woodcuts derived from Guillaume Rondelet’s (1507-1566) treatise on marine life, Libri de Piscibus Marinis (1554-1555). Each of these books covers all manner of sea creature, as Rondelet, like many scientists of his day, drew no distinction between fish, marine mammals, and invertebrates. Rondelet drew upon Classical sources as well as his own observations, experiments, and anatomical investigations, with many of the illustrations being based on specimens that he had collected and dissected. The book took two years to complete, and became an extremely influential scientific text in its day. De Natura Aquatilium Carmen is aimed at a more general audience. Here, each creature is paired with a descriptive epigram. Many of the illustrations are highly accurate, to the point that one can identify the precise genus and species that Rondelet was illustrating. A small few are less accurate, and probably represent cases where Rondelet did not actually observe the animal himself. For example, his renditions of whales are quite crude, looking more like reptiles, although they do include the accurate detail of a blowhole at the top of their heads. In addition to these identifiable species, Rondelet included a handful of fantastical creatures, such as the sea serpent, sea lion, and several varieties of mer-people. Although Rondelet expressed skepticism about their existence, he still thought it worthwhile to document them, since other, supposedly reliable witnesses had reported seeing them. Shown here is the bishop-fish (also known as the sea-bishop), a variety of merman that was allegedly observed in Poland in 1531. Rondelet stated that he was simply presenting the image of the creature that he had received second-hand, and that he neither affirmed nor denied its existence.

Medieval and Renaissance maps often included illustrations of sea monsters. Although probably included first and foremost for decorative purposes, the cartographers designing these maps usually did draw their descriptions from accounts that were regarded as scientific and accurate, such that they typically depict the kinds of creatures that cartographers and sailors expected to find living in the ocean. These images reflect both the limited understanding of the sea and the very real dangers and strangeness of seafaring at the time. Some of the creatures shown on these maps were likely derived from sightings of real animals by sailors and travelers who may have seen them only briefly or from a distance, and whose reports of strange sea creatures became distorted and exaggerated as they were circulated and retold. Even creatures that are now well known, such as whales, sharks, and the walrus, were often described and depicted in monstrous terms. (In all fairness, some of these animals can grow to nearly twice the size of the ships being used at the time, which would have made them seem all the more threatening). Many early depictions of whales take the form of the monster shown attacking a ship in the map shown here; in an earlier version of this illustration, sailors are shown throwing barrels off the ship in order to distract or scare away their attacker. Still, at least one contemporary critic, Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), complained that these sea monsters were just grotesqueries used to “fill up empty spaces.” Map monsters such as these generally began to disappear from maps by the end of the seventeenth century, in tandem with rapid advances in European understanding of the oceans.

Edward Topsell was an English minister. He authored many religious treatises, but today he is best remembered for his zoological works, which were the first major books on animals printed in England in the vernacular. These books were primarily translations of Conrad Gesner’s (1516-1565) Historicae Animalium (1551-1587), a five volume Latin encyclopedia of the animal kingdom, and one of the first modern zoological works. Topsell’s versions also reproduce the same woodcut illustrations that were presented in Gesner’s version.

In writing their zoologies, Gesner and Topsell tried to draw some distinction between observed facts and myths, but, as happened in many Early Modern natural histories, not all of the creatures described actually exist. Alongside a vast selection of real animals (of primarily European, African, and Indian origin), one finds detailed biological descriptions of such remarkable animals as the unicorn, dragon, manticore, sea serpent, and hydra, to name just a few. Some of these monsters had been described in ancient and medieval sources; others came from contemporaries who claimed to have seen them. The Histories’ descriptions of real animals also included a great deal of superstition, especially in regards to their presumed medicinal properties. Still, even though Topsell did not always write accurate science, he did provide a valuable documentary portrait of what was known, assumed, and misunderstood about the animal kingdom in his day.

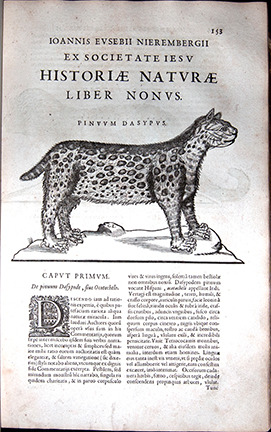

Juan Eusebio Nieremberg, a Spanish Jesuit, taught as a professor of scripture and natural history at the Jesuit college in Madrid. His Historia Naturae was a natural history of the Americas, with a primary focus on the flora and fauna of Mexico. His text is particularly interesting for having preserved the indigenous names of the plants and animals that he described. Nieremberg’s text was compiled from numerous manuscript and printed accounts. Much of his information was drawn from reports sent by Jesuit missionaries. Sixteenth century Spanish chronicles provided other major source texts. Nieremberg has sometimes been criticized for his unscientific practices, such as a tendency to include fantastical accounts and legends. However, it is important to remember that Nieremberg’s approach to natural history was deeply rooted in a theological and supernatural understanding of the world. Nieremberg perceived nature as a system born out of divine harmony and order. As such, he believed that nature could be interpreted to understand the work and will of its creator, and this was a primary focus of his scientific researches.

Sir Thomas Herbert was a British baronet, statesmen, and traveler. In 1628 the then twenty-two year old Herbert served as an attendant on a diplomatic mission to Shah Abbas I (1571-1629) of Persia. The mission itself was an utter failure: the Shah lost interest in the envoy, both English diplomats died of illness, and the survivors left having accomplished nothing. Herbert, though, went on to write an enormously popular travelogue about his travels to Persia and back, with stops in Asia and Africa. He included many descriptions of the people, customs, and wildlife of the places he visited. He also included second-hand information on places he had not visited, such as the Americas (although he sometimes implied he had seen these places). First published in 1634, the book went through five editions in Herbert’s lifetime. The copy on display is the second, expanded edition of 1638. His description of the island of Mauritius includes a contemporary account of the now-extinct Dodo bird, which was already quite scarce. He described the bird as “melancholy, as sensible of Natures injurie” in pairing its large body with small wings “serving only to prove her a bird.”

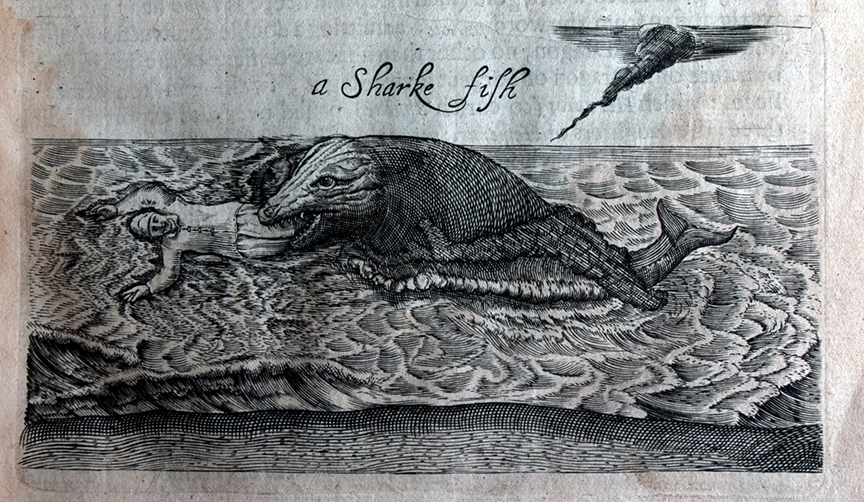

Shown here is an illustration of a “shark fish.” Herbert wrote that the shark often preyed on sailors swimming in the ocean (as is shown here), sometimes devouring them whole. He said it was equipped with a “double row of venemous teeth” and was aided in its hunt by a pilot-fish. (The reverse is true: pilot-fish follow sharks to scavenge from their kills). The engraving is crude, at best, as Herbert was well aware: he complains in the text that the image was “mistaken in the posture by the ingraver.” The engraver in question is possibly William Marshall (fl. 1617-1649), who also has the distinction of engraving a 1645 portrait of John Milton (1608-1674) that the poet lambasted as “clumsily engraved by an unskillful engraver.”

De Quadrupedibus was a posthumous collection of Aldrovandi’s writings on quadrupeds. Although generally scientific in its scope, the work also included some mythical examples, including the half-man, half-horse centaurs of Greek mythology. Most of the woodcuts presented in this volume are fairly accurate, and were probably drawn from biological specimens. These include several illustrations of African wildlife, such as the rhinoceros, the zebra, and the elephant. Shown here is a woodcut illustration of what purports to be a unicorn horn, but which can be recognized, now, as the tusk of a narwhal. Alleged unicorn horns such as this could be found in many Renaissance collections, and they were prized for their alleged medicinal powers, although, by the seventeenth century, an increasing number of scientists were aware of the horns’ actual origins. Aldrovandi himself did not go so far as to affirm or deny the unicorn’s existence. Noting that some doubted whether or not it was real, he stated that he was simply reporting what others said about the unicorn, so that his readers could draw their own conclusions.

![De quadrupedib[us]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/animalvegetablemineral/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/04/de-quadrupedib.jpg)

Ulisse Aldrovandi was an Italian physician and naturalist. While employed as a teacher of logic at the University of Bologna, Aldrovandi would use his vacation periods to travel in order to study nature and collect biological specimens for his museum, which eventually became one of the finest of its time. He was later appointed a professor of natural sciences, and did much to encourage an interest in the systematic study of natural history. Aldrovandi set out to write a complete zoological encyclopedia, though he published only four volumes in his life; many other works appeared posthumously, based on his manuscripts and notes. Although he was known for his systematic and accurate observations, he has also been criticized for repeating many unscientific legends and fables in his books. In all fairness, though, Aldrovandi, like most scientists of his day, had little choice but to rely on secondhand accounts when trying to describe remote areas. Without the ability to verify these reports – which often came from non-scientists – Aldrovandi could only relay what he had heard about the wildlife of distant lands. Despite these shortcomings, Aldrovandi’s works represented a significant advance for presenting a systematic natural history that attempted, as much as possible, to base scientific understanding on first-hand observations of biological specimens.

De Quadrupedibus Digitatis is an encyclopedic work on quadrupeds, assembled and edited after Aldrovandi’s death by Bartolommeo Ambrosini (1588-1657) and first published in 1637. The text includes everything from descriptions of animals’ anatomy and habitats to accounts of their roles in mythology and symbolism. The woodcut illustrations are relatively accurate, and it is also notable that, unlike many contemporary natural history texts, no mythological creatures are included. The animals covered derive mainly from the Western hemisphere, although a few creatures from the New World, such as the armadillo, also appear here.

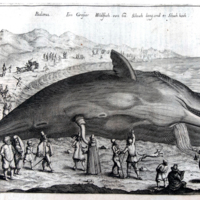

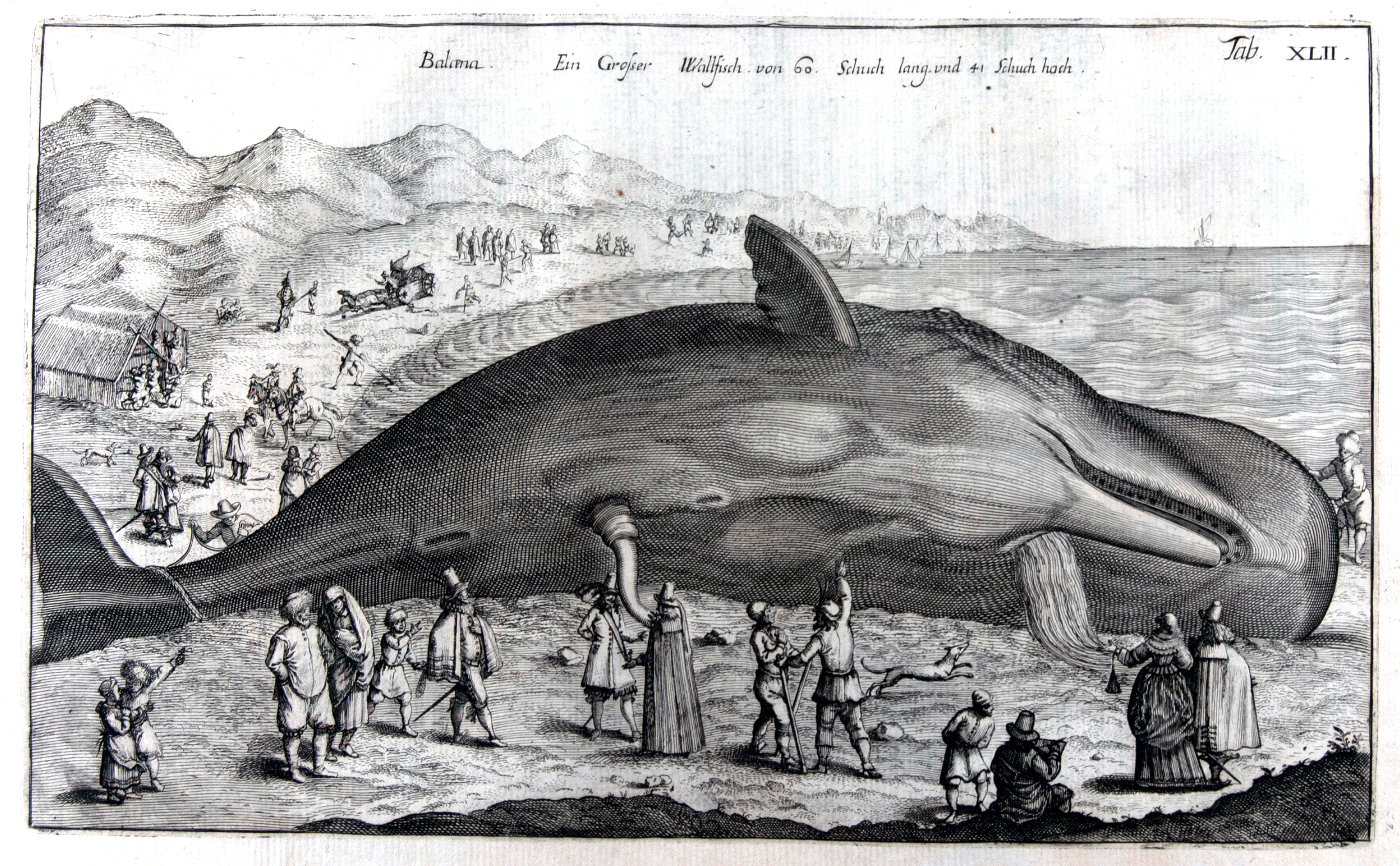

Joannes Jonstonus was a Polish physician and naturalist. His most popular work, Historia Naturalis, was a six-volume zoology. (The book shown here contains the fourth and fifth volumes, which deal with marine life). Although quite popular, Jonstonus’ books did not introduce much that was new: they were primarily compilations of earlier sources, such as Gesner (1516-1565) and Aldrovandi (1522-1605). Even the engravings were often recycled from earlier works by Belon (1517-1564), Rondelet (1507-1566), Gesner, and others. The illustrations are, nonetheless, of remarkable quality. Most of the species are displayed with a great degree of accuracy, although, as was typical, the lines between fantasy and reality are blurred, with a variety of sea serpents, merpeople, and other monsters appearing throughout. (As Jonstonus was primarily relying on the presumed accuracy of earlier sources, he would, in all fairness, have had little ability to confirm or deny the accuracy of reputed sightings). Interestingly, because the animals are presented according to a relatively orderly taxonomy, one can see what kinds of genuine animals were thought to be related to the mythical ones. For example, the Norwegian sea serpent is grouped alongside a variety of eels, a Danish sea-ape appears in the company of sharks, and a Jenny Hanniver is correctly identified as a mutilated skate or ray. Shown here is an engraving of a beached sperm whale, complete with curious onlookers. (Some of the other varieties of whale are rendered less accurately, with some bearing a closer resemblance to gigantic marine reptiles).

![De quadrupedib[us]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/animalvegetablemineral/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/04/de-quadrupedib-thumb.jpg)