Animal III

Alexander Wilson, a Scottish-American ornithologist, illustrator, and poet, is often called the Father of American Ornithology. Unlike his European counterparts, who often relied on preserved specimens shipped back from the Americas, Wilson traveled extensively through the American wilderness to observe birds in their natural habitats. His nine-volume American Ornithology described 268 species, twenty-six of which were previously unknown to Western science. The illustrations for the work were printed using copper plate engravings, with the prints subsequently colored by hand. Wilson worked closely with his engravers and colorists in order to ensure that the illustrations were true to life. Although less vibrant than the work of later naturalists, such as Audubon, the illustrations are remarkably accurate. The volume on display, from 1812, shows an illustration of the now-extinct passenger pigeon, which at the time occupied a vast range across the North American continent. Accounts such as Wilson’s provide a valuable documentary record of species that are no longer extant. Wilson described the passenger pigeon as a “remarkable bird” whose population was so immense as to nearly “surpass belief,” with “no parallel among any other.” He described watching for several hours as a flock flew over head; he later estimated that the flock must have been several miles in length. Another flock, also observed by Wilson, was so large that it blotted out the sun, like a cloud.

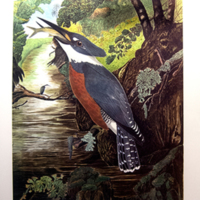

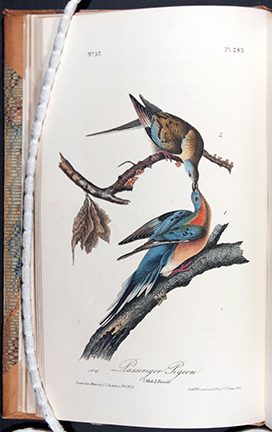

John James Audubon, a self taught naturalist and artist, was inspired by the earlier work of Alexander Wilson (1766-1813). Like Wilson, Audubon traveled extensively through the American wilderness in search of wildlife. In his Birds of America, Audubon aimed to describe and illustrate every species of bird in America. The first edition, published between 1827 and 1838, was printed to show each bird at life-size. He painted his illustrations using dead specimens as models: to show the birds in lifelike positions, they were posed using wires and threads. Containing 435 engraved plates, it described twenty-five species for the first time, along with six that are now extinct. Between 1840 and 1844, The Birds of America was reissued in a more affordable quarto format, which is shown here. (The volume on display is from 1842). This edition included sixty-five additional plates, with all of the original plates having been re-engraved under Audubon’s supervision.

Shown here is Audubon’s illustration of the passenger pigeon, which can be compared to Wilson’s earlier version. As in Wilson’s time, the passenger pigeon was still prolific. Audubon described one flock so large it blotted out the sun for three days. He provides vivid accounts of their mass migrations, as well as of their immense slaughter by human hunters. Ironically, Audubon assured his readers that, though one may “naturally conclude that such dreadful havoc would soon put an end to the species,” their population size and reproduction rate was so great that no amount of human hunting could ever put the species at risk. This assumption was a common one. Although vast flocks of the bird persisted into the 1870s, the species ultimately fell victim to catastrophic habitat loss and over-hunting. Rare by the 1890s, the last of the wild passenger pigeons was killed in 1900. The very last of their kind, a captive pigeon named Martha, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914.

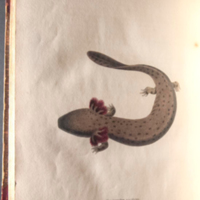

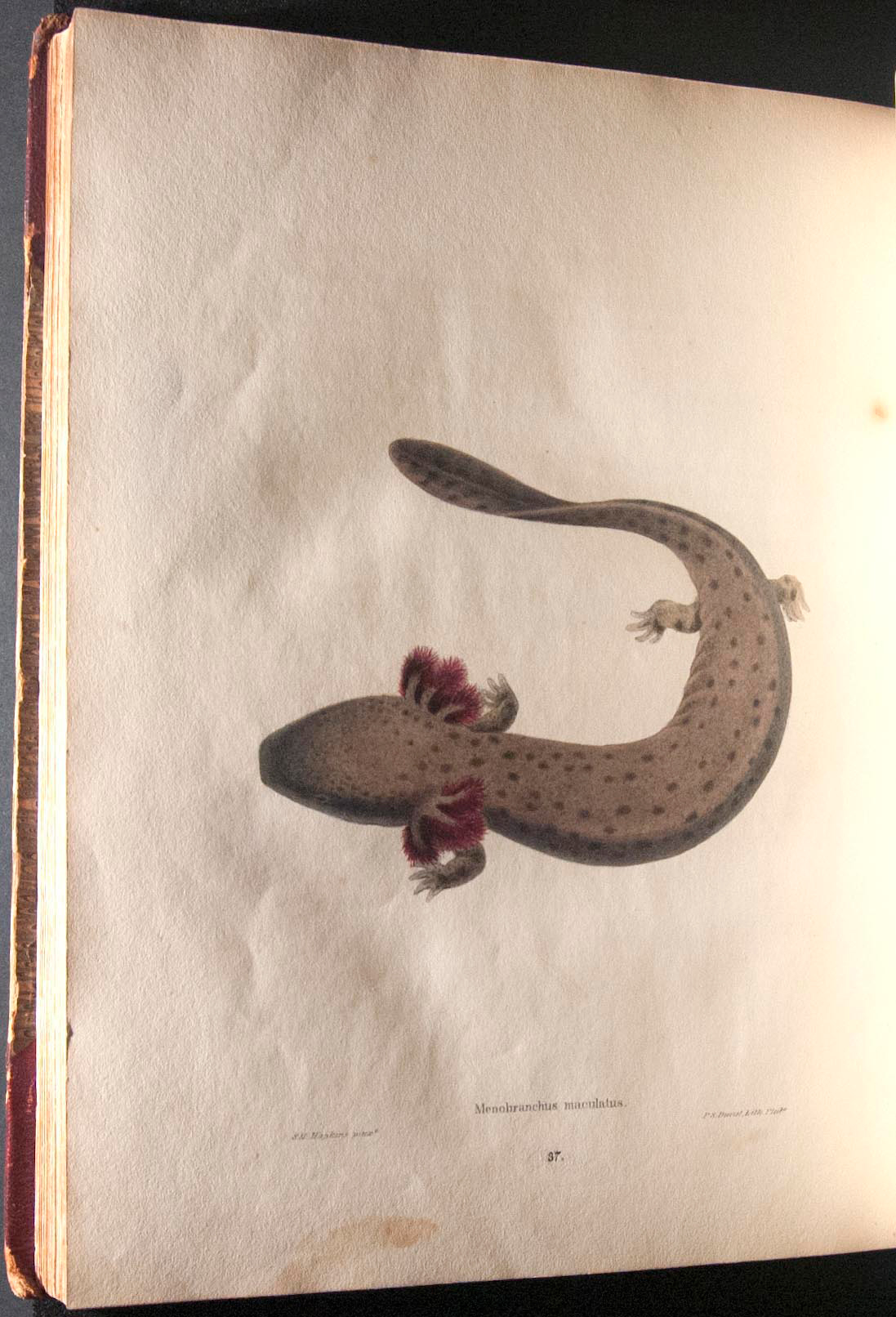

North American Herpetology was the first comprehensive, illustrated account of North American reptiles and amphibians. Holbrook believed that the accuracy of previous works had suffered from an over-reliance on dried skins and dead specimens preserved in alcohol. To ensure the accuracy of his own illustrations, Holbrook made an effort to draw as many species as possible from living specimens. The first edition appeared in four volumes between 1836 and 1840. In preparing this edition, Holbrook’s practice was to describe the species in the order that he obtained his specimens, and once he had described enough of them he would publish a volume. Thus, the organization was haphazard at best. The second edition, which is shown here, was published in five volumes in 1842 in order to accommodate the many new specimens that Holbrook had since obtained. Holbrook took advantage of the second printing to create an entirely new edition, with the species now presented according to their anatomical structures. Many of the illustrations were also entirely redrawn for accuracy. Holbrook’s work introduced twenty-nine new species in total, and surveyed the entirety of what were then the boundaries of the United States of America.

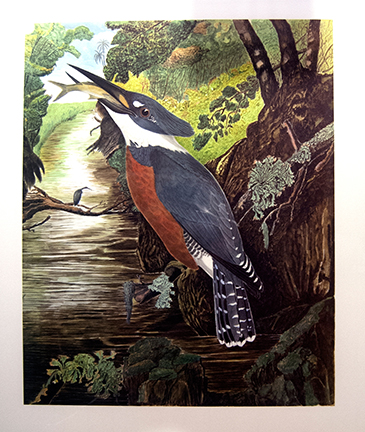

Andrew Jackson Grayson was a self-taught naturalist and artist. In 1846 he set out from Louisiana to settle in California. While living there he developed an interest in ornithology, having been inspired in particular by the double elephant folio edition of John James Audubon’s (1784-1851) Birds of North America (1827-1838), which he saw at the Mercantile Library Association in San Francisco. Audubon’s work did not extend to the Pacific coast, and, generally, the wildlife of California was still relatively unknown to Americans at the time. Grayson aimed to describe the bird species that Audubon had not covered. To this end he traveled extensively through the West coast of the United States, as well as into Mexico. During his journeys he produced extensive field notes describing a great number of species, and he produced in total 163 paintings of birds. He also collected specimens for the Smithsonian Institution, eventually contributing over a thousand to their collections. In his lifetime Grayson identified and described many new species of bird, but he left behind little in the way of published writings. Grayson had envisioned publishing a portfolio volume similar to Audubon’s, but he contracted yellow fever during one of his trips and died, leaving his work unfinished. For many years afterwards his widow, Frances Grayson (1824-1909) tried to bring her late husband’s work into print, but her efforts met with no success. She eventually donated his paintings and field notes to the Bancroft Library, where they remain to this day. Grayson’s work was finally published in 1986 by the Arion Press, over a century after his death. Two full-scale facsimiles of his paintings are shown on the wall. The originals were probably painted circa 1867.

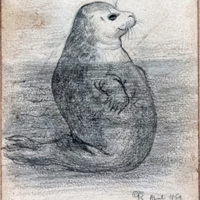

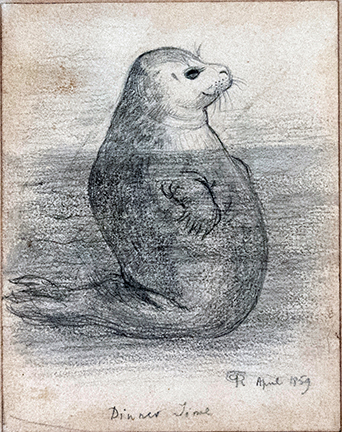

This pencil sketch by Dante Gabriel Rossetti depicts the great seal in the London Zoo. The London Zoo, which continues to operate and is now one of the oldest zoos in the world, originally opened in 1828 as a private research institution for members of the Zoological Society of London. However, in 1847 the Zoo opened its doors to the general public, allowing non-scientists such as Rossetti to view (and, in this case, document) its creatures. Rossetti was a frequent visitor to the Zoo in the 1850s, and he often chose to meet with his friends there. Rossetti is best known for his poetry and Pre-Raphaelite paintings, but he also had a great fondness for animals, and would later go on to house his own menagerie of exotic species in his gardens, often to the great consternation of his neighbors.