Vegetable

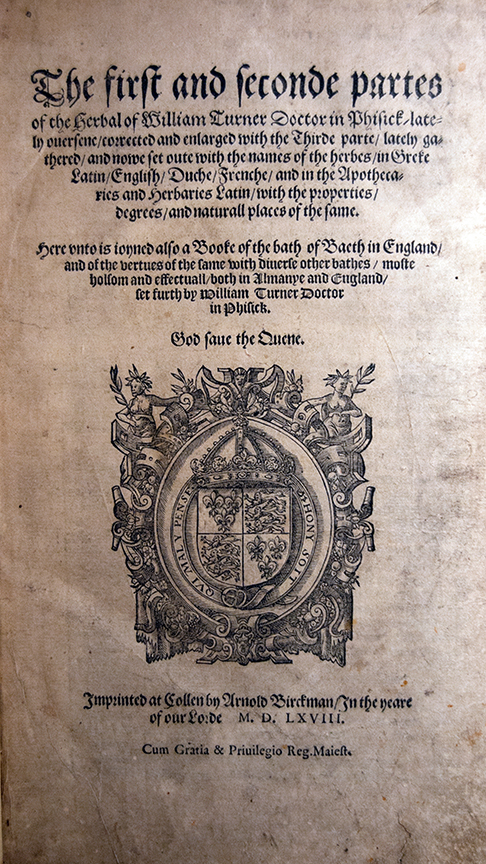

William Turner was a physician and naturalist, who has been called the father of modern English botany and ornithology. His Herbal constituted the most accurate description of English plants that had been produced up until then. The edition on display here was published in 1568, and brings together revised versions of parts one and two, along with a third section describing the virtues of various plants, and their usefulness in treating ailments. A final section describes places offering curative baths, along with guidelines for bathers. This edition features many high-quality woodcuts by Leonard Fuchs. Turner wrote the book in English in order to place knowledge of medicinal plants within the reach of laypeople, a fact he mentions in his preface.

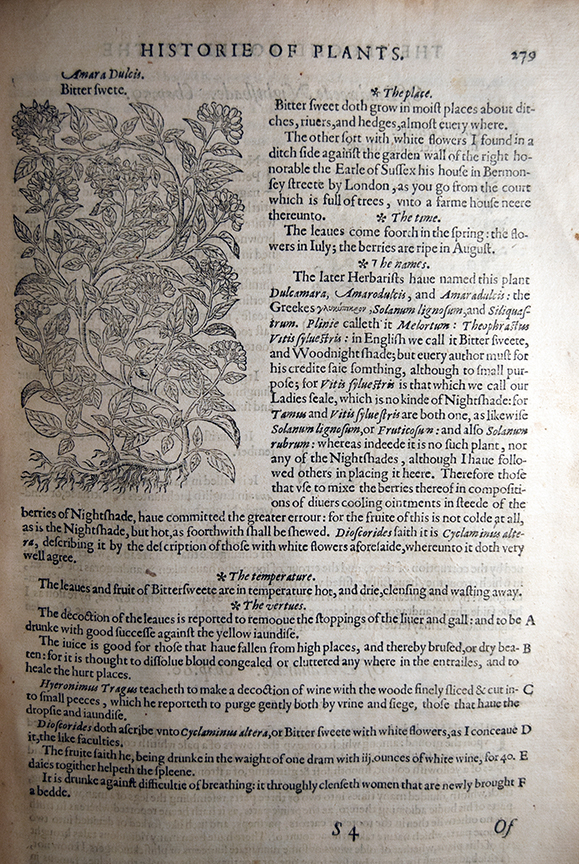

During the second half of the sixteenth century, A Nievve Herball was the most authoritative work on herbs in the English language. The work is a translation from Dutch into English of Dodoens’s widely influential Cruydboeck (“Herbal”) of 1554, by way of the French translation of the work. Dodoens was a Flemish physician and botanist. Henry Lyte, the translator, added information about plants from Somerset, his native region in England. The first edition of A Nievve Herbal was printed in Antwerp in order to include the same woodcuts as the Flemish original, which were from an earlier work, Leonard Fuch’s De Historia Stirpium (1542). A Nivevve Herball bears the distinction of being the first book in English which set out to list every known plant.

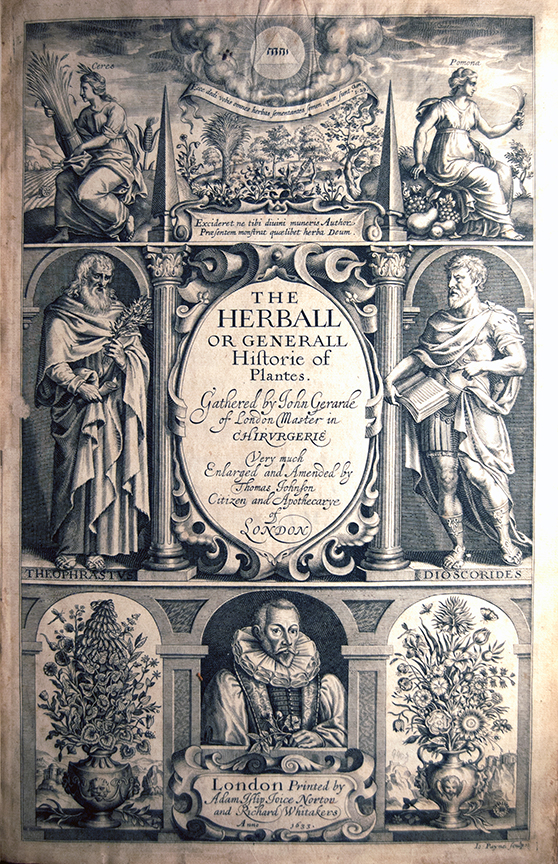

This is a first edition of what would become the most popular botanical work of the sixteenth century, despite its controversial genesis. In the 1590s bookseller-printer John Norton hired Dr. Robert Priest (a member of the Royal College of Physicians) to translate Dodoens’s herbal Stirpium Historiae Pemptades Sex into English. However, Priest died before the translation could be published. Gerard somehow got possession of the manuscript, made additions, and published it as his own work. Before the book went to publication, however, another botanist was called in to make corrections, on account of Gerard’s less than stellar Latin. Gerard grew impatient before all the corrections could be made, and forced the book to print with numerous and, at times glaring, mistakes. It enjoyed great popularity despite this.

Johnson’s edition represents the first revised version of Gerard’s Herbal from 1597, appearing twenty-one years after Gerard’s death. This edition is sometimes referred to as “Gerard emaculatus” on account of the numerous corrections and additions Johnson made. For example, the emendations are said to anticipate modern scholarship by the systematic way they are indicated in the text, by means of askterisks. The new edition contains a different set of woodblocks (2766 in total) from botanical books previously published by Christophe Plantin, a printer in Antwerp. Gerard’s edition had used a set of blocks from the massive herbal Eicones Plantarum (of Jacob Theodorus Tabernaemontanus), published in Germany in 1590. In some instances Gerard had misidentified these woodcuts in his version. The Herball is also believed to be the first book to carry an image of the potato plant. The popular, emended edition of the workcontinued to be used by botany students into the second half of the eighteenth century, and enjoyed a reputation into the nineteenth century, as well. Interestingly, even the final edition still contained a description of the legendary “goose tree,” which was believed to produce barnacle geese. The woodcut for this entry contains an image of both the tree and a goose. In the text Gerard (1636) claims to have witnessed one of the trees himself, complete with tiny hatchlings.

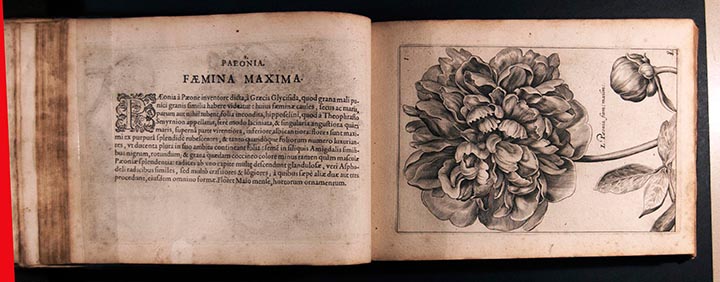

Hortus Floridus appeared in the seventeenth century during the time of a feverish trade in tulips. It contains descriptions and illustrations of two hundred flowering plants, fruit trees, fruit and medicinal herbs. The presence of Latin inscriptions on the back of all the plates suggests that this particular copy is in the earliest state of the work. (Some copies of the book have no such inscriptions). The book is noteworthy also because of the quality of its copper engravings, which were carved by Dutchman Crispijn Van de Passe the younger, along with his father and brothers. The naturalistic renderings of flowers and other plants marked a great improvement over the woodcuts that had predominated up until then. Like many other pre-Linnean European works, Hortus Floridus is more descriptive than scientific, judged by today’s standards.

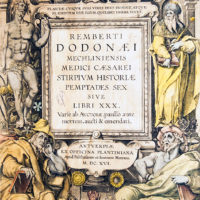

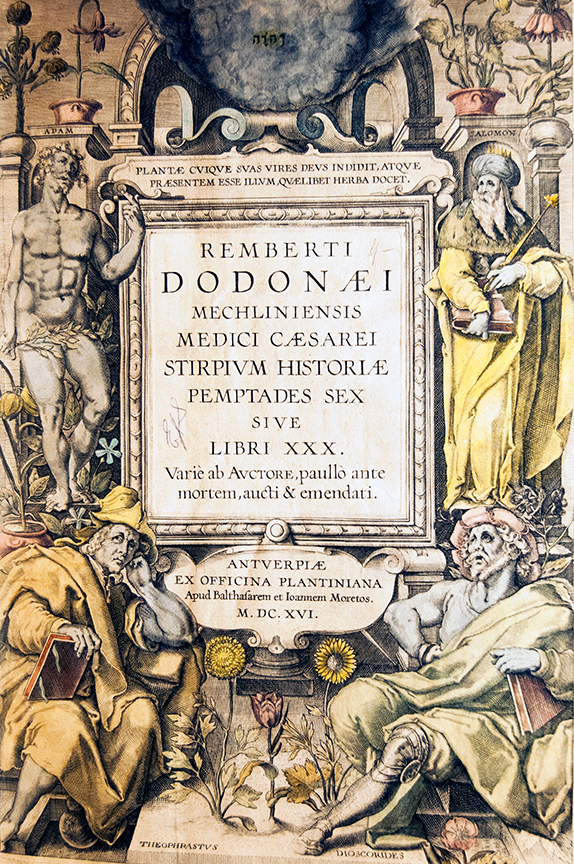

Doedoens’s Pemptades is one of the most important herbals of the 16th century, which saw the publication of works that emulated but also replaced authoritative ancient texts such as Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica (which is on display elsewhere in this exhibition.) These texts were used by doctors, apothecaries, and barber-surgeons, for the treatment of ailments. At root, the Pemptades is a revision of Dodoens’s earlier herbal Cruydeboeck, first published in Dutch in 1554. (The Cruydeboeck is also featured in this exhibition). Interestingly, a flawed translation of that text served as part of the basis of Gerard’s celebrated herbal of 1597, two versions of which are on display in this case.

This volume is a German translation of Dioscorides’s ancient, authoritative text De Materia Medica, an edition of which is on display in this case. The fact that Dioscorides was still being translated early in the seventeenth century attests to his longstanding influence on the herbals that had been written and translated in the preceding hundred years. Note the vividness of the colors used for the hand-painted woodcuts, and the Gothic or “black letter” type, which would last longer in Germany than elsewhere in Europe, where Roman typefaces became more common.

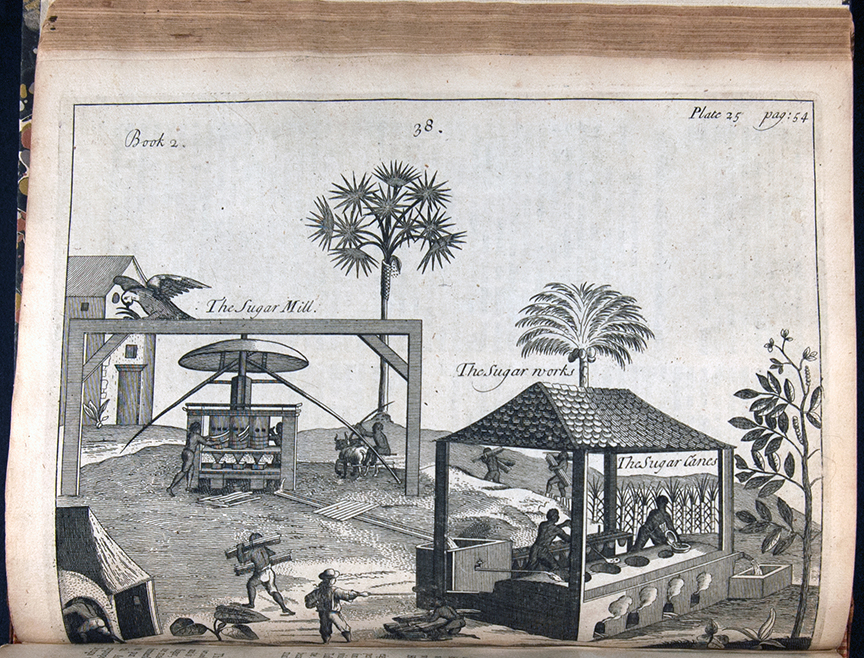

The Compleat History of Druggs falls into all three categories of books featured in this exhibition, although the plant section is the most extensive of the three. Pierre Pomet was apothecary to France’s King Louis XIV. His Histoire génerale des drogues was first published in 1684, and saw numerous editions in the years following. The volume on display here is the third edition of Pomet’s book in English. He travelled extensively in Europe collecting examples of plant, animal and mineral substances that were being used to treat various ailments. Many of the remedies were new to Europe, having arrived as a result of colonial exploration. The sense of the word “drug” had a broader meaning in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than it does now. Pomet’s remedies included plants drawn from the traditional materia medica. However, the book also described the benefits of both unicorn and rhinoceros horn, as well as ground mummy. The image displayed here presenets a sugar mill run by slave labor in the Caribbean.

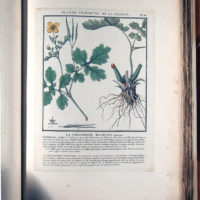

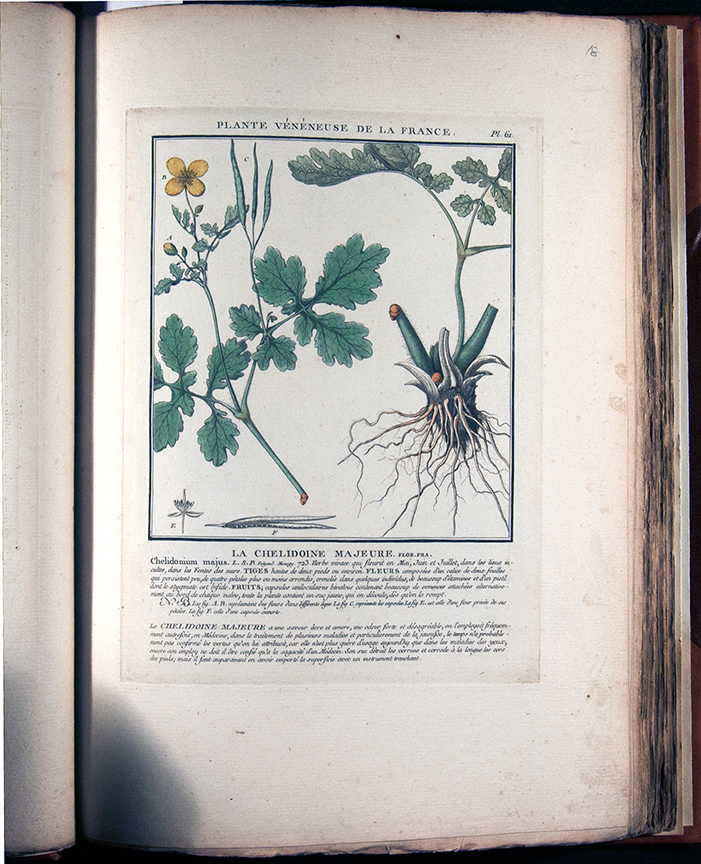

Pierre Bulliard was a French botanist who specialized in mycology, the study of mushrooms. In 1783 he published the first part of a projected multivolume work entitled Herbier de la France, intended as a scientific description of all native plants found in the kingdom of Louis XV, who reigned from 1715 to 1774. On display here are the text and plates of volume two, which describes the characteristics of dangerous plants as well as symptoms of poisoning, and offers remedies for counteracting the effects of toxins. Bulliard employed the Linnaean system of nomenclature and sexual classification. However, scholars have pointed out some inaccuracies in his use Linnaeus’s designations. Bulliard was also a master engraver and watercolorist. He executed the high quality engraved plates seen here. The book was printed by the press of “Monsieur,” the honorific title given to the eldest living brother of the French king. Not all of the Herbier de la France was completed.