Vegetable II

The Temple of Flora was originally published in 1799 as part of Robert John Thornton’s A New Description of the Sexual System of Carolus von Linnaeus. Thornton intended the book as a monument to the work of the Swedish botanist, well known for both his system of naming and his writings on sexual reproduction in plants. In preparing the illustrations for his own book, Thornton employed painters and engravers to produce glorious floral images against romantic backdrops. No expense was spared, as the goal was to assert Britain’s importance in the rapidly expanding domain of botanical knowledge. While ostensibly scientific in inspiration, The Temple of Flora is suffused with a romantic world view, as seen in both the stylized images, and the many poems that fill the pages. The cost of this ambitious endeavor ruined Thornton financially. Nonetheless, The Temple of Flora is considered one of the finest works of botanical illustration ever produced. The edition on display here is the referred to as the “quarto” version. Some plates were re-engraved and changed for this edition.

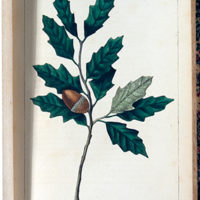

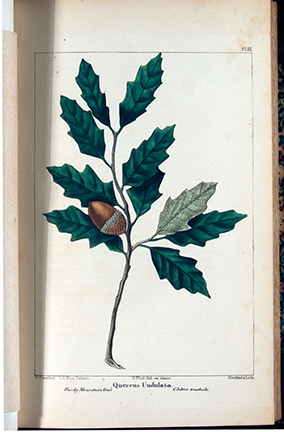

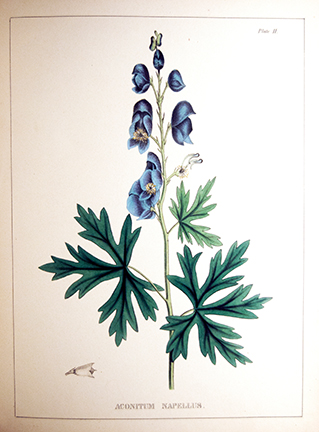

The book on display here is volume four of a work by Thornton, published after The Temple of Flora. As in that work, the goal is to present British flora (and glorify British botany) in the light of Linnaeus’s system. This volume features beautifully executed uncolored engravings, as can be seen here. The book is laid out so as to present examples of plants that fall together under Linnaean classification, which is elucidated through charts and anatomical drawings.

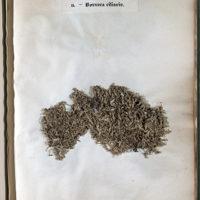

In the process known as “natural illustration” plant specimens are mounted directly to the page of a book. Created by French botanist Dominique Delise, Lichens de France is composed entirely of such specimens. Lichens are formed on the basis of a symbiotic relationship between fungus and algae or cyanobacteria. Earlier, in 1822, Delise produced Histoire des lichens, a scientific survey that used prints rather than specimens. Delise’s biography is of interest, as he was an officer in the Imperial Guard of Napoleon Bonaparte, before turning his attention to botany.

Thomas Nuttall was an English ornithologist and botanist, who carried out extensive botanical expeditions in the United States. For a time he was a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. His book is a continuation of the work of André Michaux, who produced the first three volumes of North American Sylva, starting in 1810. Nuttall’s work contains detailed descriptions of forest trees found in California, Oregon, the Rocky Mountains and elsewhere in the United States. It adds 122 vivid hand-colored lithographic plates to the 165 that appeared in Michaux’s text. An edition that brings together the volumes produced by both Michaux and Nuttall is also on display in this case.

Dr. Joseph Carson was a professor of Materia Medica (known as pharmacology today) at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, and, later, at the University of Pennsylvania. He was interested in laying out the connection between materia medica and botany. This beautifully illustrated work was published in two volumes. One can see how the text continues the tradition that goes back to Dioscorides, while incorporating the Linnaean classificatory system. The treatment of illness by means of plant substances is still the main goal of the work, as was the case in antiquity. Chromolithography, the process used to create the vivid color images of plants seen here, had become popular by the mid-nineteenth century.

This book is made up of thirty-seven specimens of Scottish sea weeds pressed and then mounted on card stock, which was then attached to the leaves of the book. The Latin name of each specimen was printed in letterpress, along with the location where it was found. The striking color seen in this example is typical of the well-preserved specimens found in the book. “Natural illustration” is the term used to describe the use of preserved specimens in books such as this. The nineteenth century saw a great deal of activity aimed at identifying and classifying plant species, often focused on specific countries.

In this scientific text, the ferns under discussion are illustrated by a technique known as “nature printing,” which uses metal plates made directly from natural specimens. Colored inks are also used in the process. The goal was to allow for more impressions than could be made by printing directly from specimens. The technique was practiced somewhat during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but proved to be uneconomical. Henry Bradbury, the nature-printer of this particular volume, learned the technique from the Viennese printer Auer Alois, who had perfected it. However, Bradbury then obtained a British patent without informing Auer. Before printing the two octavo volumes of this edition, Bradbury and Evans produced a larger, nature-printed folio volume of ferns of Great Britain and Ireland.

This four-volume work is another example of the nature-printing technique, in which an impression is made directly from a plant, that impression then being used as the basis for a print. Each volume of this work presents a different order of algae found in the British Isles. Scientific descriptions of each plant are accompanied by smaller engravings showing dissections. One can see in this example how the technique produces wonderfully detailed images, with vivid color. The nature-printing technique worked particularly well with ferns and seaweeds, on account of their thin, two-dimensional fronds.