Thucydides (circa 460-400 BCE)

Θουκυδιδου του Ολορου περι του Πελοπουυησιακου πολεμου βιβλια οκτω. Thucydidis Olori Filii De Bello Peloponnesiaco Libri Octo. [Geneva:] Excudebat Henricus Stephanus, illustris viri Huldrichi Fuggeri typographus, 1564.

Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian Wars – here printed in the original Greek and in the Latin translation of Lorenzo Vallas, as edited and rewritten by Henri Estienne II – was not, in and of itself, particularly controversial. What was controversial was the printer himself, Estienne (here Latinized as Henricus Stephanus), and in the case of this volume a censor responded by crossing out Estienne’s name every time it appeared in print. Henri Estienne’s father, Robert Estienne, had routinely been accused of heresy for his printings of the Bible, in particular for his printings of the original Greek text of the New Testament. (Many Church authorities viewed the Latin Vulgate as the only valid version, even though the Vulgate was, itself, a translation from Hebrew and Greek.) Under the reign of King Francis I, Robert had served as the king’s printer and was thus benefited from the king’s protection. After Francis’ death in 1547, Robert’s situation deteriorated and he fled to Geneva, where he converted to Calvinism and reestablished his printing press under the protection of the Genevan authorities. Henri followed Robert to Geneva in 1555, and he continued the press after Robert’s death. (Other members of the Estienne family remained in France and also printed under the Estienne name.) Because of these religious and political tensions, the Genevan Estienne imprints were prohibited in France and restricted elsewhere. Apparently, in the case of this volume, a censor decided that it would be acceptable as long as the offending Estienne name was expunged.

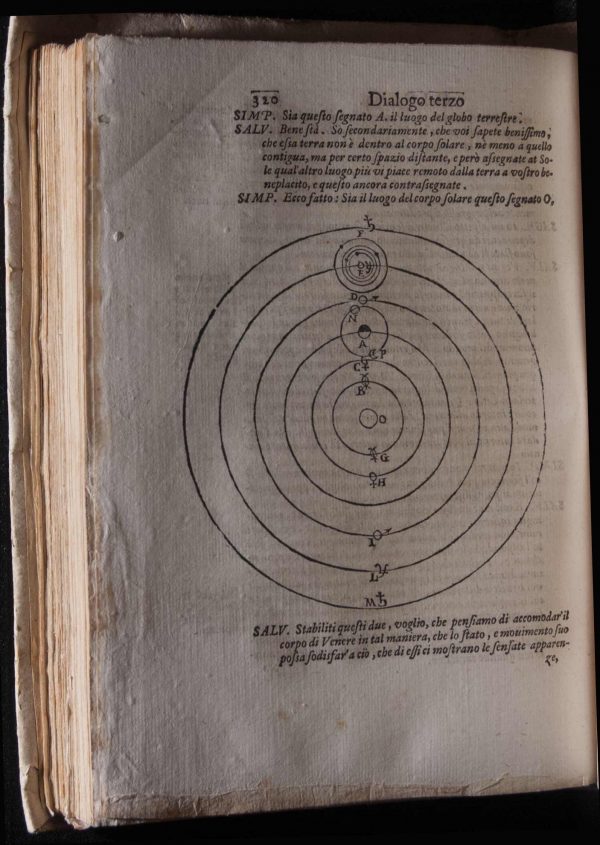

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

Dialogo Di Galileo Galilei Linceo Matematico Sopraordinario Dello Studio Di Pisa. E Filosofo, E Matematico Primario Del Serenissimo Gr. Duca Di Toscana. Doue Ne I Congressi Di Quattro Giornate Si Discorre Sopra I Due Massimi Sistemi Del Mondo Tolemaico, E Copernicano: Proponendo Indeterminatamente Le Ragioni Filosofiche, E Naturali Tanto Per L'vna, Quanto Per L'altra Parte. In Fiorenza: Per Gio: Batista Landini, 1632.

Galileo’s Dialogo presents an analysis of the theories of the universe, comparing Copernicus’ heliocentric theory (i.e., that the planets revolve around the sun) to the older geocentric theory (i.e., that the universe revolves around the earth) proposed by Ptolemy. This was far more controversial than it sounds today: the Ptolemaic theory had long been established in the scientific community and, more importantly, the Inquisition had condemned heliocentric theory as heretical. At a time when heresy was a capital crime, this was a truly dangerous argument. In writing the Dialogo Galileo had tried to distance himself by presenting the competing theories in the form of a conversation between three characters. This way, Galileo could say that he was just writing hypothetically about heliocentric theory, and was not endorsing any theory in particular. However, the book, as written, presents a pretty one-sided argument in favor of heliocentric theory. Most of the arguments for geocentric theory are voiced by the character Simplicio, who is portrayed throughout as a fool. All the more problematically, some of Simplicio’s arguments were the very same theological arguments that had been voiced by Pope Urban VIII. This did not go over well. The Pope first organized a special commission to review the book, and then referred the matter to the Roman Inquisition. Galileo was brought before the Inquisition, forced him to recant, on pain of death, and was sentenced to house arrest for the remainder of his life. The Dialogo itself was banned by the Inquisition and added to the Catholic Church’s List of Forbidden Books, making this copy a rare survival. The ban on the Dialogo was not lifted until 1835.

Albert Einstein (1879-1955)

Die Grundlage Der Allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1916.

This volume presents the first individual printing of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. In 1905, Einstein had presented his theory of special relativity, which concerned objects in motion and contained the famous equation “e=mc 2,” which expressed the concept of mass-energy equivalent. In his writings on general relativity, Einstein theorized that the force of gravity results from the curvature of space and time, with planets and other massive objects further altering this force. Einstein’s theories have revolutionized our understanding of physics and rewrote many prior assumptions about the nature of space, time, matter, energy, and gravity.

In 1933, following Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany, the Nazi Propaganda Ministry instituted an extensive and pervasive censorship policy, which involved banning and destroying works that were in any way perceived as contrary to the Nazi regime’s ideology and worldview. In particular, the Nazi’s Anti-Semitic persecutions were so pervasive and systematic that they even sought to erase the written scientific, cultural, and literary contributions that Jewish authors had produced. All of Einstein’s works were banned, not so much because of the scientific theories they described but because of the fact that Einstein was Jewish and his scientific accomplishments were thus seen as contradicting the racist foundations of Hitler’s Germany. A number of Einstein’s German critics – including two Nobel laureates, Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark – did not even bother to assess his scientific theories, and simply dismissed them on racist grounds.

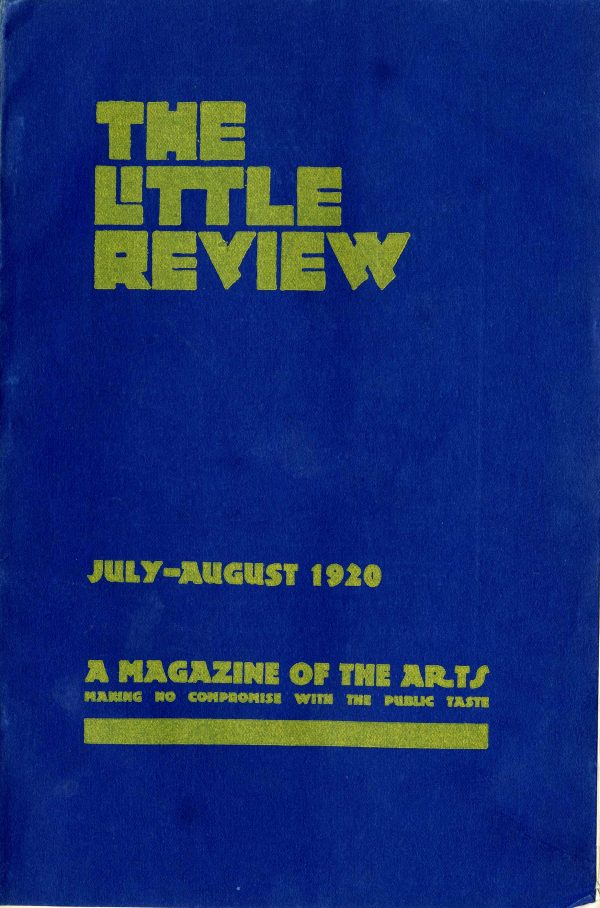

James Joyce (1882-1941)

“Ulysses, Episode XIII.” The Little Review. New York: Margaret C. Anderson, July-August 1920.

Ulysses was first published in installments in The Little Review between March 1918 and December 1920. The novel’s serialization ended abruptly after the Society for the Prevention of Vice in New York lodged a formal complaint, charging The Little Review with printing obscenities. Specifically, the Society took issue with an erotic scene that appeared in the thirteenth installment (now known as the “Nausicaä” episode), which appeared in the issue shown here. (The scene in question is heavily coded and metaphoric; one has to read pretty closely to realize that anything of the sort is happening in the scene in question.) The editors of The Little Review, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, fought back in court but lost. They were fined $50 for their troubles and were banned from printing any more of Ulysses. At this time, copies of The Little Review were also seized by the US Post office and burned. Ulysses was published in full in France and England in 1922; it remained banned in the United States, although pirated American editions were produced between 1927 and 1928. An authorized edition did not appear in this country until 1934, after Random House successfully sued to overturn the ban, on the grounds that Ulysses was not pornographic and thus could not be considered obscene.

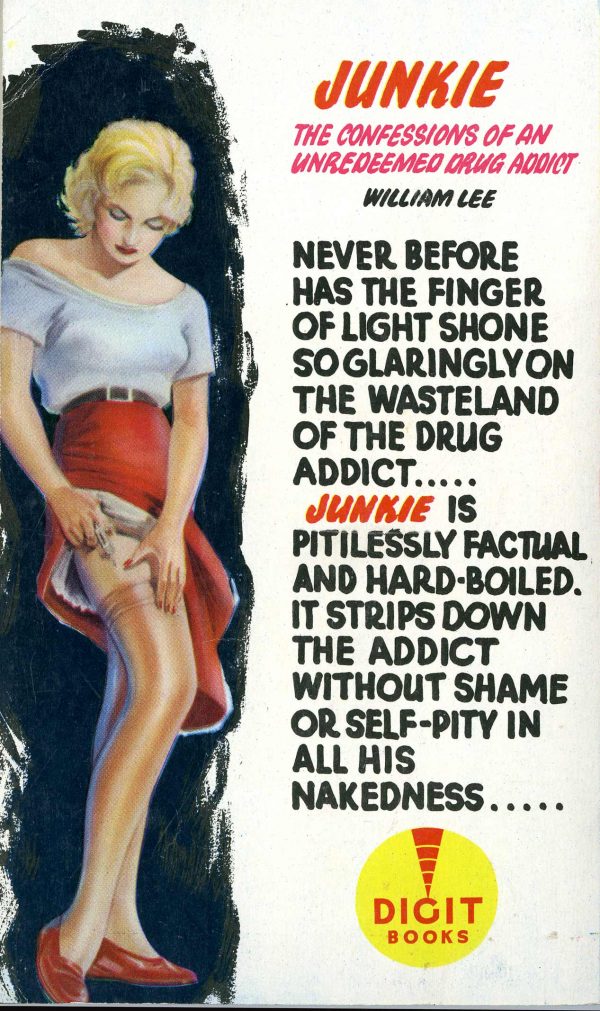

William Lee [i.e, William S. Burroughs (1914-1997)]

Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict. London: Brown, Watson Ltd, [1957.]

William S. Burroughs’ first novel, Junkie, originally appeared under a pseudonym in 1953. It was printed in an Ace Double-Books edition, where it was paired with Narcotic Agent, the memoir of a federal narcotics agent. The volume shown here was the first separate printing of Junkie, as well as the first British edition. Although Burroughs’ novel presented a straightforward and uncritical account of his own drug use, his publishers opted to couch it in an anti-drug context. Their preface presented Junkie as a harrowing account and a valuable warning against the “drug menace.” The original pairing with Narcotic Agent had helped to further bolster the publishers’ claim that they were not actually endorsing Burroughs’ account. The British edition retained the same cautious preface, but the British authorities were not impressed. The cover art, which was sensational for the time, probably did not help their case. British censors banned the book almost immediately upon publication, and nearly all copies were recalled to be destroyed.