Although mass demonstrations were a key part of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, they were not the only means by which people challenged forces of oppression. Quieter forms of activism, such as investigating abuses of power, filing strategic lawsuits, or educating members of the community, were just as vital for disrupting unjust social structures.

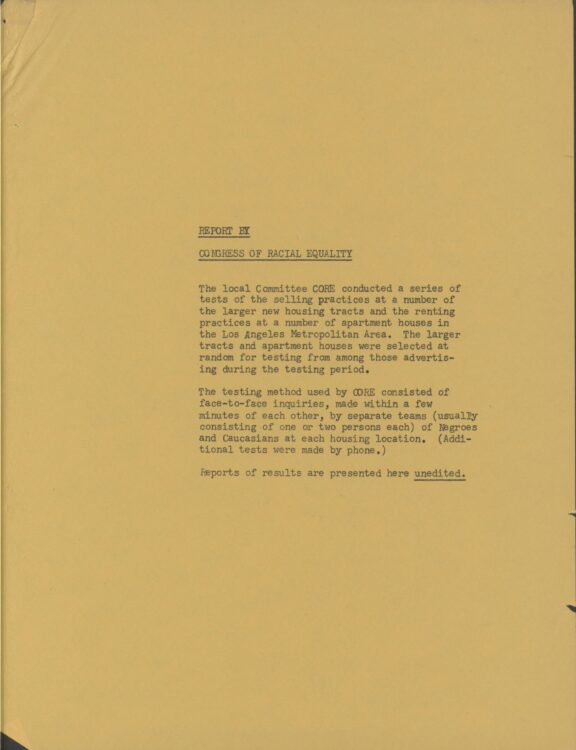

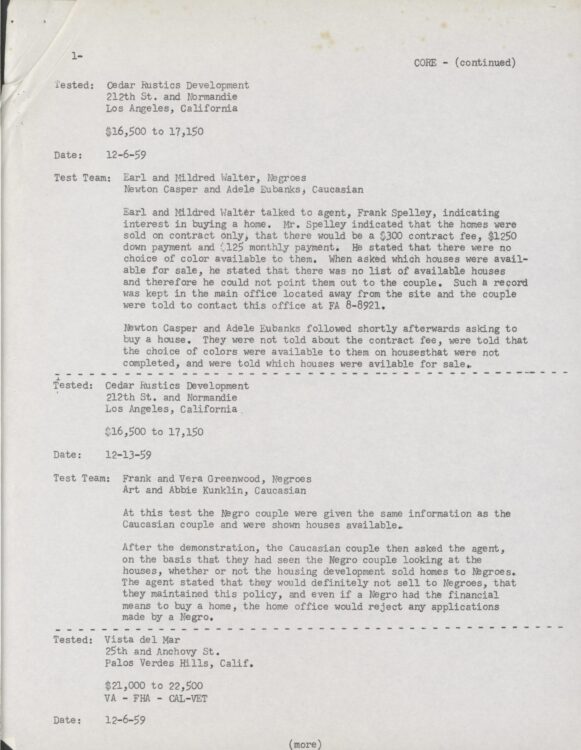

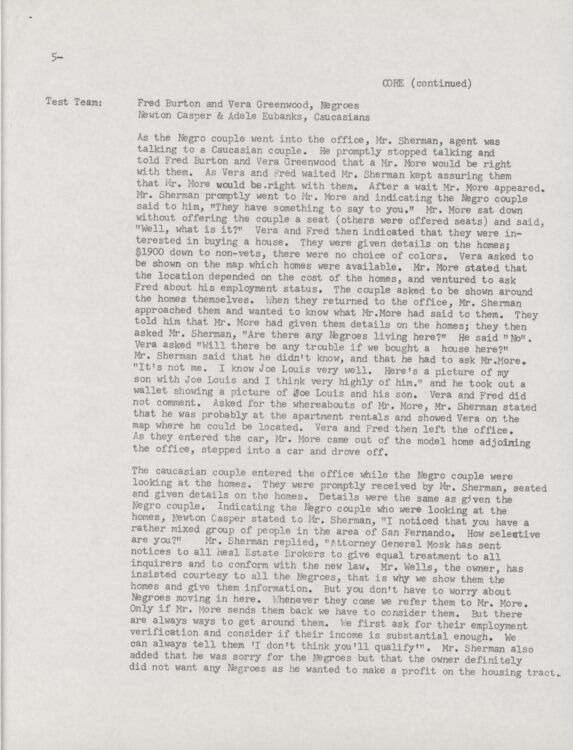

In order to fight against injustice, one often has to prove first that injustice exists. In 1959, a Los Angeles CORE group sought to gather concrete examples of housing discrimination in the area. Despite having recently been made illegal, refusing to rent or sell based on an individual’s race was still a widespread practice. Volunteers affiliated with CORE posed as potential renters and homebuyers at real estate offices and gathered data on their treatment. As a result of the meticulous work of those who visited the offices and assembled this report, the organization had evidence that could then be used to pressure the city to better enforce laws regarding equal treatment, to argue a case in court, or to rally future demonstrators around the cause of fair housing.

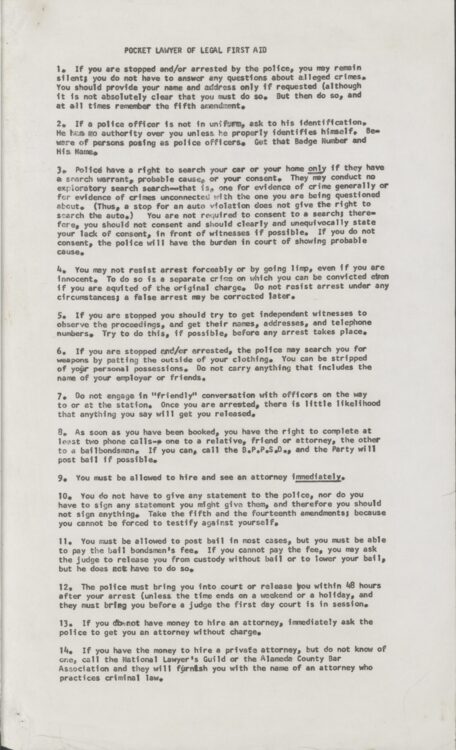

It was vital for activists in the movement to have a working knowledge of the law and their rights as citizens. By knowing what constituted a lawful arrest, what was a violation of their rights, and what their own legal obligations were, they could better challenge abuses of authority. One of the Black Panther Party’s primary missions was to put an end to police brutality, especially in Black communities. They circulated this “Pocket Lawyer” so that everyone, whether members of the Party or not, could have some basic guidance for how to handle police confrontations and what to do if arrested.