In the first half of the twentieth century, private corporations and the U.S. federal government increasingly looked to the western United States and its territories for resource extraction. This section features photographs and a lithograph that aestheticize extractive forms of human intervention on the natural environment. Through the work of human engineers and laborers, water is converted into a commodifiable resource and fire is bound up in the extraction and burning of fossil fuels. Artists documented, framed, and aestheticized these processes, not only because these photographs and lithograph possessed artistic qualities, but also because they could appeal to the senses of the viewer. This is most apparent in the photograph Richfield Oil Well Fire, El Segundo, CA and in Adrian D. Clem’s lithograph Construction Work, Boulder Dam #5. Similarly, the sites portrayed in Clem’s lithograph and the postcard of Multnomah Falls are modern tourist attractions where visitors’ access to and experience of these sites are activated by extractive practices. As vernacular photographic and print forms that were created and circulated within mainstream channels (i.e. newspapers, print-making practices, and postcards), these objects implicate the viewer in the process of aestheticizing extractive systems.

In this cinematic image, the Richfield oil well fire that ignited in December of 1937 appears as a natural event and aestheticizes the extraction of petroleum in Southern California.[1] It is near-impossible to distinguish the well from the flames that burst above it.[2] Rather, the photograph compels our senses to apprehend the scale of the fire, to imagine its brightness and its blazing heat. Though oil well fires are quite dangerous and difficult to extinguish, the passive stances of the onlookers suggest that the fire is a controlled spectacle that will eventually dwindle. Between the obscured oil well and the casual presence of spectators, even a caustic oil well fire—something so disruptive to the essential cycles of wildfires—appears natural. By extension, this photograph blends oil extraction and its resulting fires into California’s desert environments.

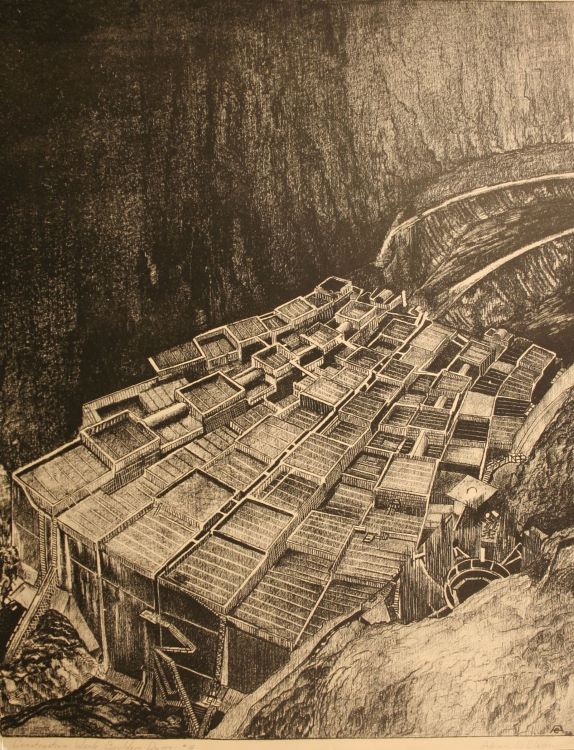

Adrian D. Clem’s lithograph belongs to a larger series of prints that document and position the construction of the Boulder Dam—more famously known as the Hoover Dam—as a massive engineering feat, capable of converting the Colorado River into hydroelectric power. Beginning in 1933, approximately 215 concrete blocks ranging from 25 to 60 square feet in size were vertically stacked and reinforced with concrete in the Black Canyon between Nevada and Arizona.[3] Ladders that ascend the façade in the lithograph’s foreground indicate the monumental scale of the structure—even in its early formation—and the amount of labor required to build it. Many industrial, large-scale dams such as the Hoover Dam are colonial structures, as they displace groups of human and non-human agents, and transform water and rivers into commodifiable resources, often under the guise of a monumental landmark. The attention to the dam’s construction obscures the fact that dams endanger ecologies from the erosion of downstream rivers, to the depletion of fish and plant populations, and the overall disruption of rivers’ cycles.[4]

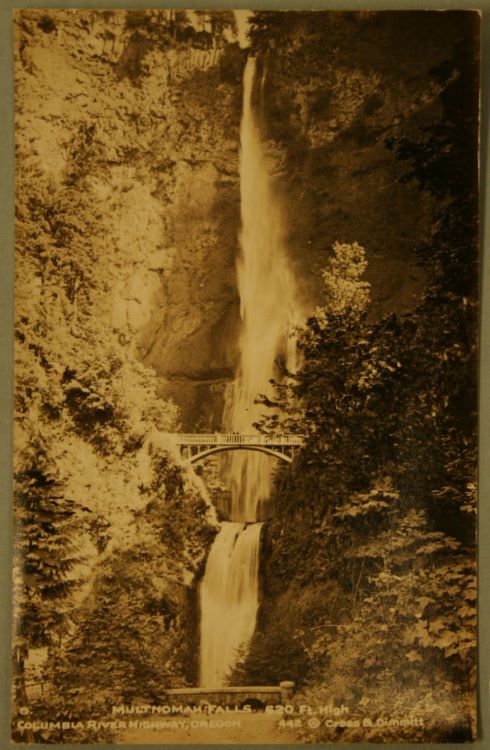

A postcard displaying a photograph of Multnomah Falls evidences the growing human presence at the Columbia River Gorge made possible by the first waves of growing petroculture infrastructures, particularly highway systems.[5] Centered in the image is Benson Bridge, constructed in 1914 to allow tourists to observe the 620-foot falls up close. The photograph appears to have been taken from the highway bridge at the foot of the waterfall that was part of the Columbia River Highway, completed in 1922. From this perspective, the postcard conveys the grandeur of the falls in relation to man-made structures. The Benson Bridge appears dwarfed between the canyon-like formations of land. It emerges spontaneously from the lush vegetation and forestry on either side of the waterfall as if it were constructed to blend in or appear as a natural form in the environment.

[1] This is a phenomenon that art historian Catherine Zuromskis has explored in landscape photography and petromodernity of the later twentieth century. See Catherine Zuromskis, “Petroaesthetics and Landscape Photography: New Topographics, Edward Burtynsky, and the Culture of Peak Oil,” in Oil Culture, eds. Ross Barrett and Daniel Worden, pp. 289-308 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

[2] Located fourteen miles outside of Los Angeles, the oil field in El Segundo was part of increased efforts to extract petroleum in Southern California during the early twentieth century. By the time this oil well fire combusted, ten companies were responsible for the establishment of twenty-seven oil wells in the course of two years. The oil well represented in this photograph belonged to the Richfield Oil Corporation, later acquired by British Petroleum (BP) in 2000. See L. E. Porter, “El Segundo, Oil Field, California,” Trans. Vol 127, no. 1 (1938): 81-90.

[3] Construction was executed on the Ancestral Lands of the Southern Paiute, Hualapai, Mohave, Hopi, and Zuni. See Jane Griffith, “Hoover Damn: Land, Labor, and Settler Colonial Production,” Cultural Studies <–> Critical Methodologies, vol. 17, 1 (2016): 30-40. Construction logistics can be found at “Hoover Dam,” Bureau of Reclamation. Accessed April 18th, 2024. https://www.usbr.gov/lc/hooverdam/faqs/damfaqs.html#:~:text=Five%20years.,employed%20during%20the%20dam's%20construction%3F.

[4] Lisa Blackmore, “Turbulent River Times: Art and Hydropower in Latin America’s Extractive Zones,” in Liquid Ecologies in Latin American and Caribbean Art, eds. Lisa Blackmore and Liliana Gómez, pp. 13-34 (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2020); Martin V. Melosi, Precious Commodity: The Environmental Impact of the Big Dam Era (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011).

[5] As a tourist attraction, Multnomah Falls has been discreetly caught up in the growing petrocultures of the twentieth century. Increased production in the car industry led to greater demands for better roads and highway infrastructures. Entrepreneur Samuel Hill proposed a highway that would route through the Columbia River Gorge and Cascade Mountain range to provide better access to scenic vistas and natural landmarks.