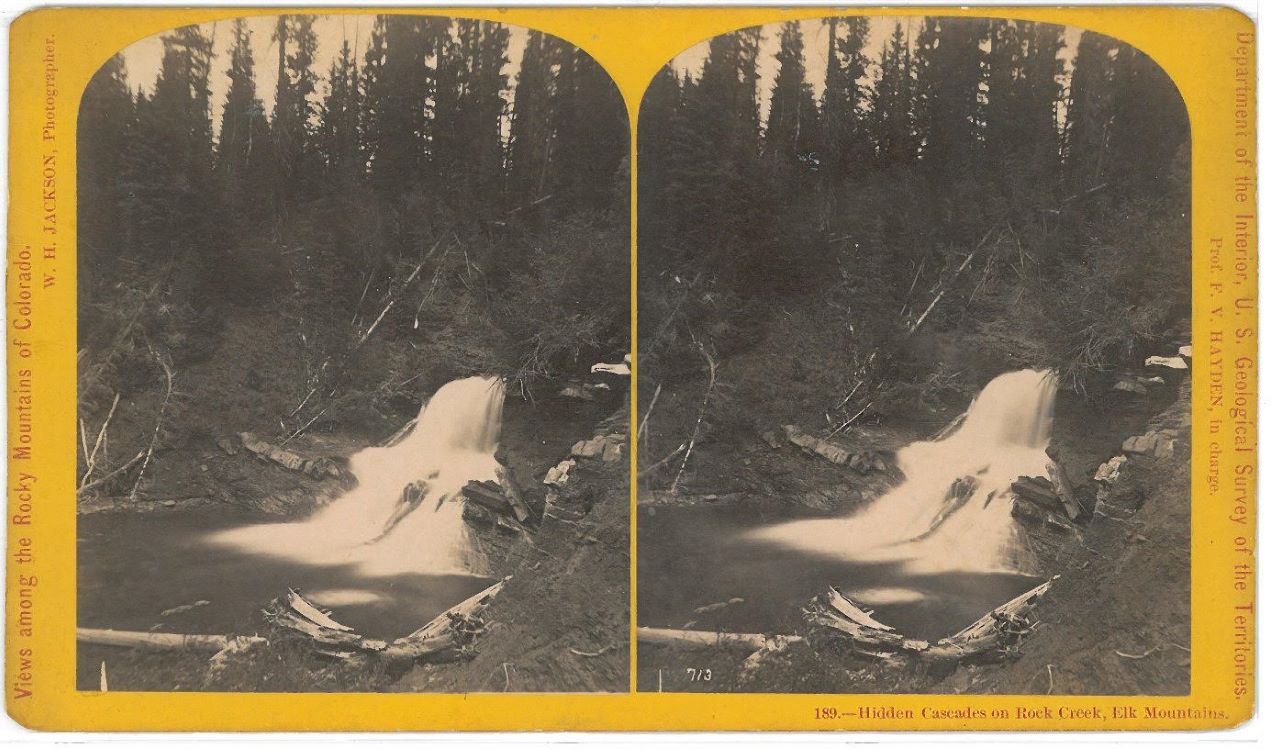

The history of landscape photography between the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is entangled in colonial practices. As territories in the western United States were charted, mapped, and studied, photography became a visual tool for surveying and communicating topographical information. Photographers framed and documented land according to the settler-colonial spatial politics of the state which depended on the displacement and erasure of Indigenous Nations. The photographs in this section date to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hidden Cascades on Rock Creek, Elk Mountains was taken by William Henry Jackson, who worked as the photographer for the Hayden Geological Survey of the Yellowstone River in the Wyoming Territory and as the official photographer for the U.S. Geological and Geographical Surveys of the Territories from 1871 to 1878. The photographs of volcanic eruptions were taken by an unknown photographer in the Territory of Hawai‘i. Though Jackson’s photograph and the volcanic photographs were taken for different reasons, the material contexts and modifications of photographic representations of land, fire, and water appealed to colonial constructs of “American” territories.

This section of the exhibition focuses on the material manipulations of photographs of water and fire that turned them from photographs into photo-objects, the combined photographic image and its material form and context. Human intervention on the environment begins with their presence in the natural world before creating photo-objects like these. Here, it also relates to the physical manipulation and contextualization of these images. As they developed, modified, and framed photographic images, photographers—both trained and amateur—introduced new layers of material meaning.[1]

Hidden Cascades is a photo-object of a Colorado mountain range that William Henry Jackson created according to colonial documentary practices.[2] “Views Among the Rocky Mountains of Colorado” is printed on the left side of the card along with Jackson’s name. On the opposite side, the card reads “Department of the Interior, U.S. Geographical Survey. Prof F.V. Hayden, in charge.”[3] With two identical images pasted side-by-side on a yellow card, this photograph was intended to be viewed as a projection from a stereopticon that could entice the colonial imaginations of his audience. The word “hidden” in reference to the Cascades also suggests an element of discovery in the taking of this photograph; the spontaneity of the jutting water paralleling the surprise of a chance encounter. Once hidden, the cascades are now revealed to viewers and the federal government, documented in detail, charted, and incorporated into the State like an inheritance.

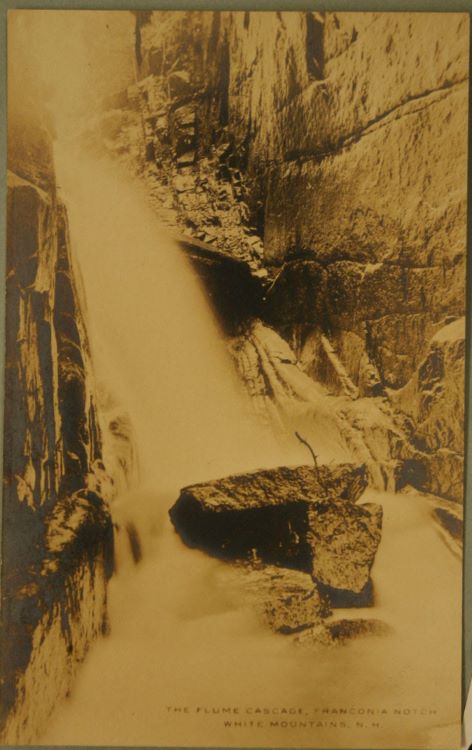

Sometimes photo-objects could be colonial based on the circuits in which they traveled. Postcards like The Flume Cascade, White Mountains, N.H. carried the potential to transform land into landmarks and sites all while rendering them materially possessable. In purchasing these postcards as a souvenir of a visit to these natural landmarks, tourists imitated the expeditions of surveyors and landscape photographers. If sent or exchanged, these postcards entered a social circuit through which visual information of distant regions could be materially engaged by the viewer without having ever visited the site themselves.

A pair of gelatin silver photographs became photo-objects when someone hand-tinted them to convey an experiential interpretation of a volcanic eruption in the Territory of Hawai‘i. While both photographs are undated, it is likely that they captured an eruption in the Halemaʻumaʻu crater of the shield volcano Kīlauea in 1924, specifically one of the many explosions of steam that occurred throughout May.[4] Since the ash and debris of these explosions were naturally gray in color, the unrealistic yellows and oranges create a dramatized interpretation of the event for viewers who might not have been present at the eruption. They were not intended to scientifically chart the Territory of Hawai‘i, but rather lend theatricality and mystery to the volcanic activity that created the islands.

[1] In her examination of the materiality of photographs, Elizabeth Edwards writes that the photo-object is created according to certain cultural expectancies and possesses its own cultural functions. See Elizabeth Edwards, “Photos as Objects of Memory,” in The Object Reader, edited by Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins, pp. 331-342 (Routledge, 2009).

[2] As Jarrod Hore has observed, landscape photographers of the late nineteenth-century, especially those who worked as part of federal geographical surveys, had the power to articulate a settler-colonial imagination of land possession as well as frame and order the land according to spatial politics of the state. Jarrod Hore, Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Settler Colonialism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022).

[3] In 1871, Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden hired Jackson to photograph and document the Yellowstone River in Wyoming Territory as part of the Hayden Geological Survey. Following their expedition, the U.S. Congress passed an act that created Yellowstone National Park. For the next seven years, Jackson worked as the official photographer for the U.S. Geological and Geographical Surveys of the Territories. It was during this time that he photographed Hidden Cascades on Rock Creek, Elk Mountains.

[4] For detailed information about this eruption, see “The May 1924 Explosive Eruption of Kīlauea.” United States Geological Survey, accessed May 20th, 2024. https://www.usgs.gov/volcanoes/kilauea/science/may-1924-explosive-eruption-kilauea