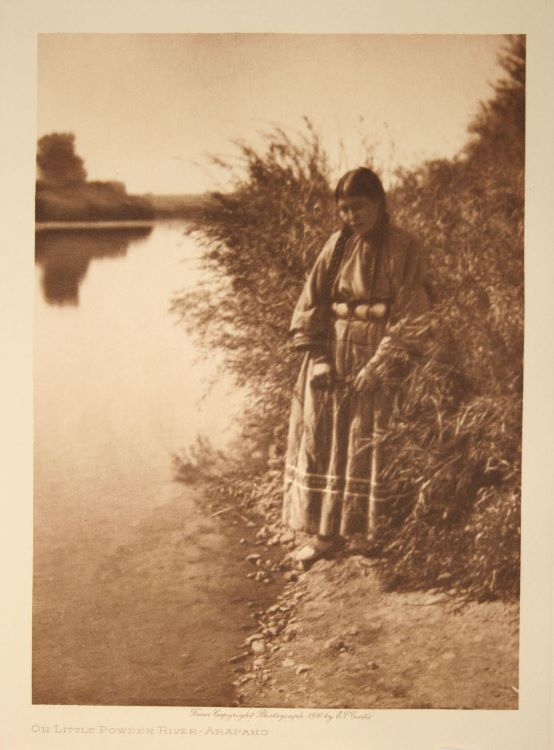

Early twentieth-century photographs of human subjects in natural environments reveal that this imagery both shaped and was shaped by relationships between humans and nature. The photographs in this section address the ways audiences might have engaged with images of the environment, especially ones that featured human subjects. Photographers had the ability to construct views that insisted on particular types of relationships between humans and the natural world. While the subjects of these photographs are human, natural elements—here in particular, water—are integral in conveying symbolic meanings and experiential qualities of these landscapes and their climates to an intended audience. Sometimes these ideas permeated into Anglo-American constructions of race. For example, the brush and river in Edward S. Curtis’s photograph The Little Powder River Arapaho may have informed how white audiences racialized the depicted Indigenous woman. Audiences therefore played a key role in making meaning from each of these photographs. This section contends with photographs of human beings in different landscapes, understanding that their presence is a physical intervention on land itself while recognizing that the photographer and the beholder of these photographs play a role in this intervention as well.

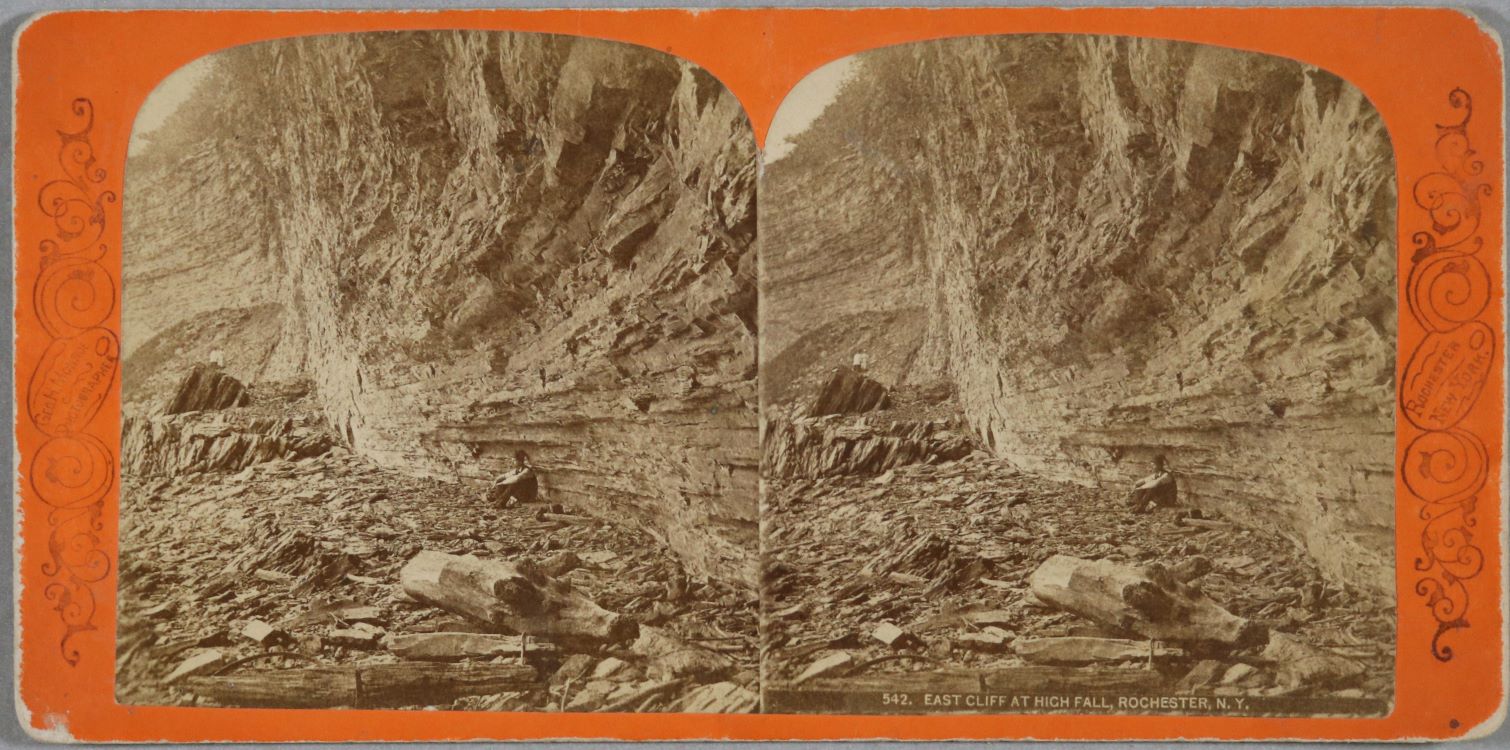

Mounted on a stereopticon card, the material form of High Fall, Rochester, NY suggests that the photograph was taken with an audience in mind. The doubled image was intended to be viewed through the lenses of a stereoscope, a device that joins the side-by-side photographs to create a subtle three-dimensional image. Though it appears rocky and arid, the landscape portrayed in the photograph is one of the curved rock faces adjacent to a waterfall located in western New York. A seated man seems tiny in comparison to the rocky façade behind him. When viewed through a stereoscope, the foreground might extend outward to add depth to the image and further envelop the human figure in the surrounding landscape. Similarly, the jagged rocks would convey a sense of tactility, enticing and transporting the viewer into this landscape as the photographer. In the same way the images are joined by the lens to render a three-dimensional landscape, the viewer is invited to piece together a sensorial experience of this particular environment captured in a single moment of time.

Edward S. Curtis’s The Little Powder River Arapaho appealed to a predominantly white audience who might have believed that the Arapaho were one of the many “vanishing” Indigenous Nations and Tribes.[1] The photograph was initially published in his twenty-volume survey of Native American Nations titled The North American Indian. Curtis intended for the photographs in The North American Indian to preserve the cultures, traditions, languages, and histories of Indigenous groups, a notion that stems from a myth that figures Native Nations as a “vanishing race.”[2] At the same time exhaustive extractive regimes occupied the western United States, federal land use considerations vacillated between what could be converted into “resources” and what should be preserved, decisions that ultimately dictated the forced removal of Indigenous Nations from their ancestral lands. In this photograph, the Little Powder River echoes the stillness and pensiveness of the Indigenous woman, welcoming white audience members to draw a mirrored narrative between the two subjects: the waters of Little Powder River gesture to the Indigenous woman as part of a “vanishing race” while her presence similarly triggers a consideration of the river’s environs as part of a “vanishing” ancestral land.

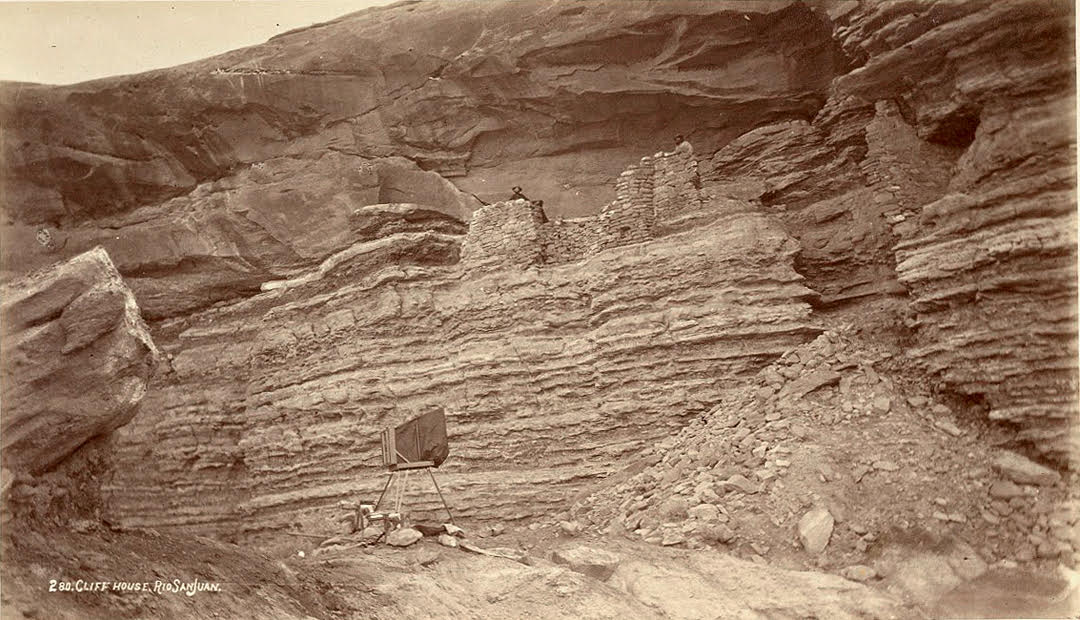

In this photograph, the camera becomes a subject and invites modern audiences to adopt a surveyor’s perspective as they examine the sites at hand. It was likely taken in southeastern Utah during the U.S. Geological Survey of the Territories led by geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden, for which William Henry Jackson served as the primary photographer.[3] Here the roughly 700-year-old man-made structures, built from stone and mud mortar, appear to blend seamlessly into the landscape. Similarly, two male figures whose heads peer out from behind the walls almost disappear within the ruins themselves. The camera anchors the viewer in the year 1875 even though the landscape that surrounds it seems timeless. Thus, Jackson’s photographs from this expedition present certain slippages: white Americans might have conflated modern Puebloan cultures with the timelines and abandoned state of the Anasazi structures, further affirming the Anglo-American myth of “vanishing” Indigenous cultures.

[1] It is unclear if the woman in the photograph is part of the Northern Arapaho Tribe or the Southern Arapaho Tribe.

[2] In the nineteenth century, white Americans constructed the “vanishing race” myth, a belief that Indigenous populations and cultures were disappearing. As a salvage ethnography, The North American Indian conveys a doubled temporality inherent in this myth. American historian Nick Yablon has examined ethnographic photographs’ abilities to project Indigenous cultures into the past while preserving them for future viewers. See Nick Yablon, “For the Future Viewer: Salvage Ethnography and Edward Curtis’s ‘The Oath - Apsaroke',” Journal of American Studies 55, no. 1 (2019): 165-195.

[3] For the published report from this particular expedition, see: W. H. Holmes, W. H. Jackson, and D. Emil Bessels, A notice of the ancient remains of southwestern Colorado examined during the summer of 1875. A notice of the ancient ruins in Arizona and Utah lying about the Rio San Juan. The human remains found near the ancient ruins of southwestern Colorado and New Mexico. (Washington: Department of the Interior, March 21st, 1876). https://hdl.handle.net/2027/miun.abb3707.0001.001