Geoffrey Chaucer, –1400

The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. [Hammersmith, Middlesex]: Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex, finished on the 8th day of May, 1896

The most ambitious publication of the Kelmscott Press, the Kelmscott Chaucer was the culmination of a love of the fourteenth-century poet which began when Morris and his friend, Edward Burne-Jones, were students at Oxford in the 1850s. Over four years, Morris designed not only the Chaucer and Troy typefaces, but also 14 large borders, 18 different frames round the illustrations, 26 initial letters, and a calligraphic title-page, all while increasingly ill and involved in the socialist cause. Production went through various complications, including problems with the specially made paper and difficulties obtaining permission to use the authoritative text published by Oxford University Press. The result was a masterpiece. Burne-Jones, who had himself delayed publication by increasing the number of illustrations from 40 to 87, memorably called it “a pocket cathedral … the finest book ever printed; if W. M. had done nothing else it would be enough.” The Friends of the University of Delaware Library funded the acquisition of this copy in 1983.

Geoffrey Chaucer, –1400

The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. [Hammersmith, Middlesex]: Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex, finished on the 8th day of May, 1896

Although Morris was the principal force behind the Kelmscott Press, he did not work alone. Professionals were employed to set type and operate the hand presses, while commercial firms did the binding and supplied ink, paper, and vellum to Morris’ specifications. Friends and associates helped, too, among them the printing expert, Emery Walker (whose 1888 slide lecture on illustrated books stimulated Morris’ founding of the Press), publisher and editor Fredrick Startridge Ellis, and Sydney Cockerell, who became the Press’ secretary. The drawings by the Press’ principal illustrator, Burne-Jones, necessitated further collaboration. Produced in soft pencil, these had to be made suitable for printing through a convoluted (and avant-garde) process which involved photographs by Walker being worked over in ink by another artist, Robert Catterson-Smith, before being transferred to woodblocks for cutting by the engraver, William Harcourt Hooper. Morris inscribed this copy of the Kelmscott Chaucer to Catterson-Smith. It is one of about a dozen he was able to sign before his death in October 1896.

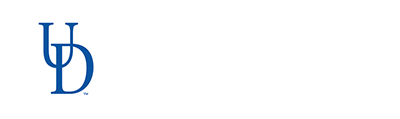

Frederick Hollyer, 1837–1933

William Morris

Photograph, platinotype, 1894

A photographer specializing in portraits of writers and artists and in the reproduction of paintings, Hollyer took this image of a thoughtful Morris halfway into the production of the Kelmscott Chaucer.

Kelmscott Press

Kelmscott Press Edition of Chaucer’s Works. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896]

This notice, informing subscribers of prices for the various bindings available for the forthcoming Kelmscott Chaucer, shows the care Morris and his associates took in printing even the smallest piece of what would now be called ephemera.

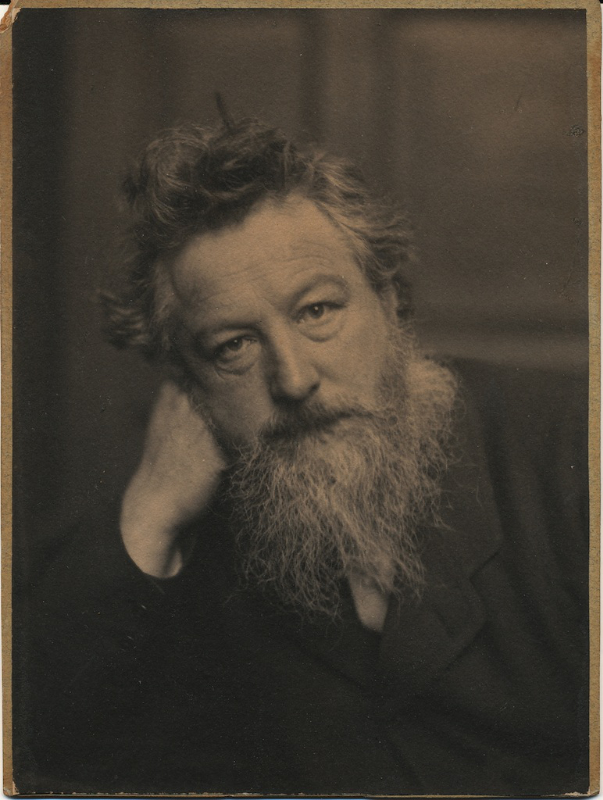

William Morris, 1834–1896

Design for a border for The Well at World’s End

Ink and pencil with Chinese white on paper, ca. 1893

The brilliance and ability Morris brought to designing floral patterns—his wallpapers and textiles continue to be manufactured today, albeit often in altered form—is shown in this original drawing for one of the borders for The Well at the World’s End. His daughter, May Morris, herself a talented designer and needleworker, described how her father could sit at a table, with a pen, brush, and dishes of black and white ink and effortlessly create this kind of intricate, perfect work.

William Morris, 1834–1896

The Well at the World’s End. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896]

Beginning in the late 1880s, after gaining fame as a poet, Morris started to write lengthy tales of love, conflict, and honor set in an imaginary age not Victorian but not quite medieval. These “prose romances,” influenced by the Old Norse sagas Morris loved (and translated) had a profound effect on such writers as J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis and are considered precursors of modern fantasy literature. The Well at the World’s End was intended to have been illustrated by a young Birmingham artist, Arthur J. Gaskin, but Morris chose to replace his work with that of Burne-Jones. Morris’ wife Jane (a famed model for the Pre-Raphaelite painters and an embroiderer) presented this copy to Hugh Thackeray Turner, an architect who served as the secretary of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, an organization (still extant) William Morris founded in 1877.

William Morris, 1834–1896

William Morris’ pen and paint brush

Bird quill and wood, made by Charles Roberson and Company, London, ca. 1890s

These relics were preserved by Morris’ close friend and associate, Emery Walker. Walker’s daughter, Dorothy, in turn gave it to the American letterpress printer, poet, and educator, Loyd Haberly, an ardent fan of Morris whose own books owed much to the example of Kelmscott.

William Morris, 1834–1896

News from Nowhere, or, An Epoch of Rest: Being Some Chapters from a Utopian Romance. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1892]

News from Nowhere remains the best-known of Morris’ writings. Originally serialized in Morris’ socialist newspaper, The Commonweal, in 1890 as a rebuttal to Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward 2000-1887 (1888), which predicted a world benefitting from advanced technology, it envisions a future, pastoral, post-socialist revolution England in which capitalism, class, industrialization, and (to some extent) sexism have disappeared. The iconic frontispiece to the Kelmscott Press edition, by Charles M. Gere, shows Morris’ country house in Oxfordshire, Kelmscott Manor, the model for the “house by the river” lovingly described in the book.

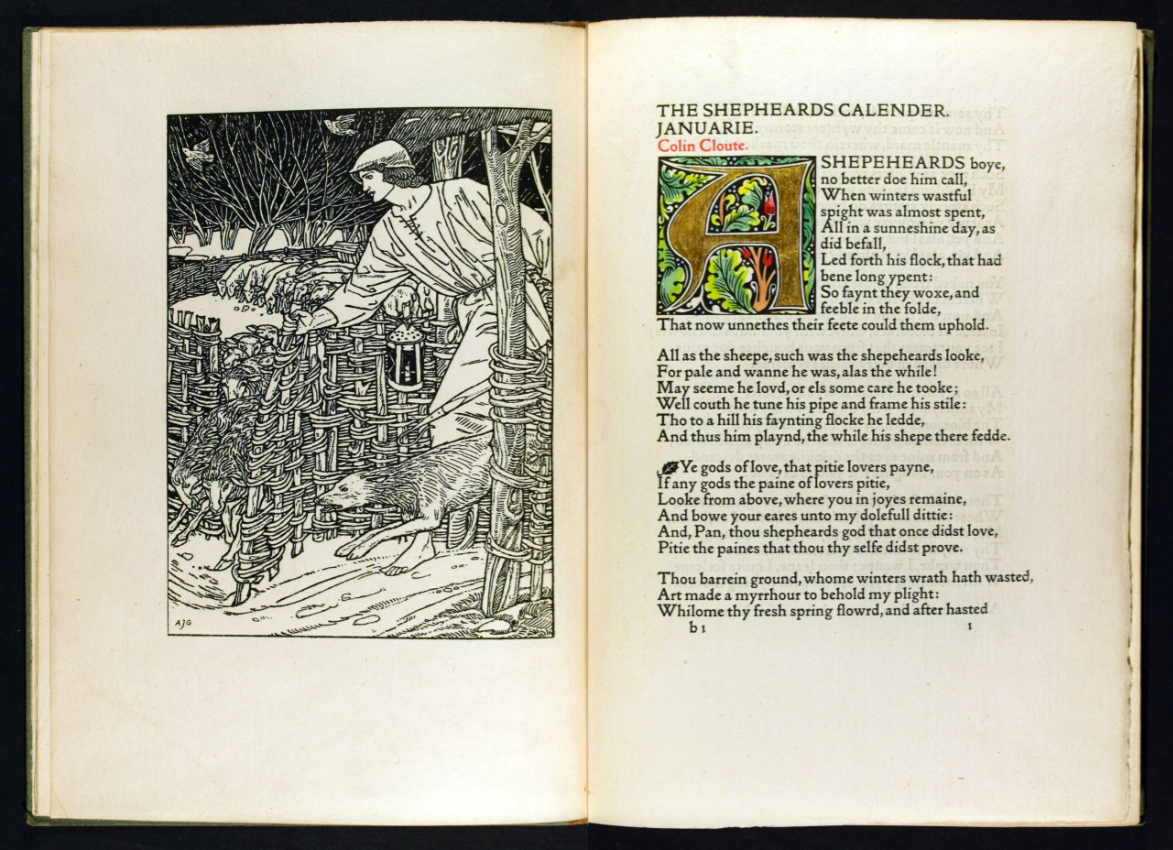

Edmund Spenser, 1552?–1599

The Shepheardes Calender: Conteyning Twelve Eglogues, Poportionable to the Twelve Monethes. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896

Edmund Spenser's Shepheardes Calendar was the first of several posthumous books issued by the Kelmscott Press before it closed in 1898. Some consider the twelve woodcuts by Arthur J. Gaskin, whose drawings for The Well at the World’s End Morris had rejected, to be even more successful than Burne-Jones’ illustrations.

Jacobus de Voraigne, approximately 1220–1298

The Golden Legend. Hammersmith [London, England]: Kelmscott Press; London: Sold by Bernard Quaritch, 1892

Although there was some input from others, Morris published only what he wanted to publish. While his own writings formed the bulk of the Kelmscott list (in this sense he was a self-publisher as well as typographer), the books included works by friends (Algernon Swinburne, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Ruskin, and Wilfrid Scawen Blunt) and by poets he admired (Shelley, Tennyson, Keats, Shakespeare), along with oddities such as a Biblia Innocentium written for children and Sidonia the Sorceress, a fake-medieval tale by Wilhelm Meinhold, translated from the German by Lady Jane Wilde, Oscar’s mother. Especially appropriate to the Press’ typography were medieval texts Morris admired and enjoyed. The Golden Legend was one of these, a collection of saints’ lives compiled in the mid thirteenth century by a Dominican friar who became Archbishop of Genoa. William Caxton, the first English printer, had translated and published it in 1493. Morris intended to make The Golden Legend the inaugural product of the Kelmscott Press — hence the name given to the typeface in which it was printed — but he was hampered by its length, problems with the paper, and his not owning a copy of Caxton s edition, He was forced to issue several shorter books before it appeared in October 1892 with two Burne-Jones illustrations in the first of the three large volumes.

![Geoffrey Chaucer, –1400. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. [Hammersmith, Middlesex]: Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex, finished on the 8th day of May, 1896 (1) Geoffrey Chaucer, –1400. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. [Hammersmith, Middlesex]: Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex, finished on the 8th day of May, 1896 (1)](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/kelmscott-chaucer-125-anniversary/wp-content/uploads/sites/240/2021/06/kelmscott-COMBO.jpg)

![Geoffrey Chaucer, –1400. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. [Hammersmith, Middlesex]: Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex, finished on the 8th day of May, 1896 (msl copy) Geoffrey Chaucer, –1400. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. [Hammersmith, Middlesex]: Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex, finished on the 8th day of May, 1896 (msl copy)](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/kelmscott-chaucer-125-anniversary/wp-content/uploads/sites/240/2021/06/msl-kelmscott-COMBO.jpg)

![Geoffrey Chaucer, –1400. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. [Hammersmith, Middlesex]: Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex, finished on the 8th day of May, 1896 (msl copy) (inscription) Geoffrey Chaucer, –1400. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, Now Newly Imprinted. [Hammersmith, Middlesex]: Printed by me William Morris at the Kelmscott Press, Upper Mall, Hammersmith, in the County of Middlesex, finished on the 8th day of May, 1896 (msl copy) (inscription)](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/kelmscott-chaucer-125-anniversary/wp-content/uploads/sites/240/2021/06/Chaucer.Works_.Kelmsoctt.inscrip.MSL_.jpg)

![Kelmscott Press. Kelmscott Press Edition of Chaucer’s Works. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896] Kelmscott Press. Kelmscott Press Edition of Chaucer’s Works. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/kelmscott-chaucer-125-anniversary/wp-content/uploads/sites/240/2021/06/kelmcott-press.jpg)

![William Morris, 18934–1896. The Well at the World’s End. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896] William Morris, 18934–1896. The Well at the World’s End. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/kelmscott-chaucer-125-anniversary/wp-content/uploads/sites/240/2021/06/Morris.Well_.MSL_.2674.png)

![William Morris, 1834–1896. News from Nowhere, or, An Epoch of Rest: Being Some Chapters from a Utopian Romance. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1892] William Morris, 1834–1896. News from Nowhere, or, An Epoch of Rest: Being Some Chapters from a Utopian Romance. [Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1892]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/kelmscott-chaucer-125-anniversary/wp-content/uploads/sites/240/2021/06/news-from-nowhere-COMBO.jpg)

![Jacobus de Voraigne, approximately 1220–1298. The Golden Legend. Hammersmith [London, England]: Kelmscott Press; London: Sold by Bernard Quaritch, 1892 Jacobus de Voraigne, approximately 1220–1298. The Golden Legend. Hammersmith [London, England]: Kelmscott Press; London: Sold by Bernard Quaritch, 1892](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/kelmscott-chaucer-125-anniversary/wp-content/uploads/sites/240/2021/06/golden-legend-COMBO.jpg)