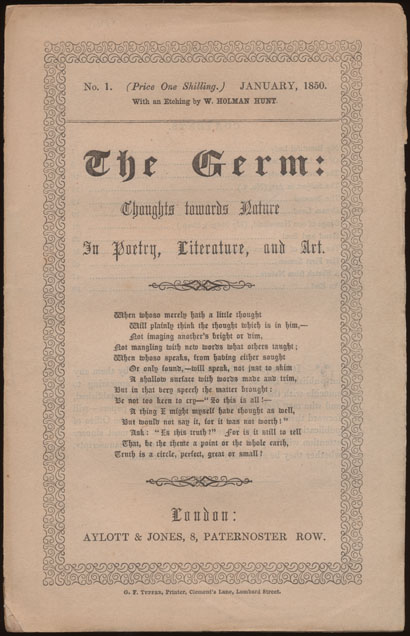

Considered the first “little magazine,” this outlet of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood includes the initial publication of Rossetti’s early verse—“The Blessed Damozel,” “Sonnets for Pictures,” and several other poems, all revised and included in Poems—as well as the prose story “Hand and Soul,” which appears in the first proofs of Poems but was not included in the final version. The germ was in some ways a Rossetti family affair, with contributions from Dante Gabriel’s sister, the poet Christina and from their brother, William Michael Rossetti, who served as editor. Other contributors to the four numbers issued were the sculptor, Thomas Woolner, poet Coventry Patmore, and painters Ford Madox Brown, Walter Deverell, James Collinson, and William Holman Hunt.

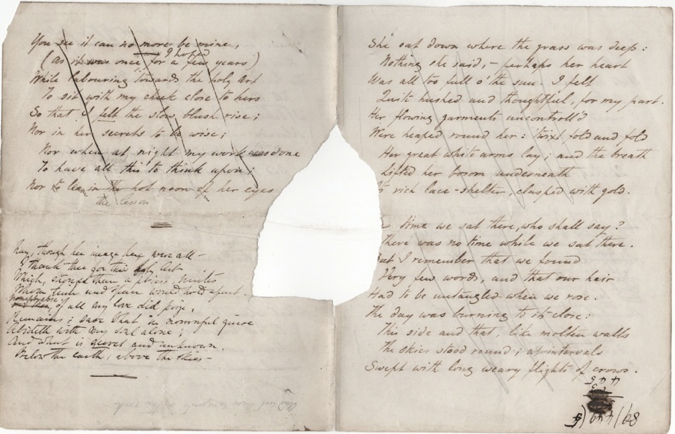

Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti’s wife, muse, model, and herself a poet and artist, died of an overdose of laudanum in February 1852. In his grief, Rossetti placed the manuscript book of his original poems in her coffin. Seven years later, at work on Poems and lacking copies of some of his early verse, he arranged for an exhumation in October 1869 to recover the notebook. This manuscript, damaged and with a large hole at the center, almost certainly came from the grave (similar manuscripts are at Harvard and Yale). The poem was largely rewritten before its publication as “The Portrait” in Poems.

Rossetti intended to include “ After the French liberation of Italy” in Poems, but rejected it as too risqué. Only a few proofs survive, this one given to Rossetti’s friend, the poet and artist William Bell Scott.

A rare separate proof of a poem included in Poems. This example also belonged to William Bell Scott.

The only complete copy known of the “first proofs” dating from the summer of 1869, this was the author’s own set and later passed into the hands of his brother, William Michael Rossetti. These proofs end with the prose story, “Hand and Soul,” used to fill out the book’s contents prior to the writing of more poems and the exhumed manuscript book.

After dropping the story from the early proofs for Poems, Rossetti privately issued this “offprint,” supposedly circulated in an edition of a hundred copies. He inscribed this copy to the woodworker-poet, Thomas Dixon.

A second volume of proofs which belonged to William Bell Scott’s lover, Alice Boyd, this volume incorporates poems taken from the manuscript book exhumed in October 1869 and other poems added to the book in 1870. In her handwritten table of contents Boyd has marked the items recovered from Siddall’s grave—making this known as one of the “exhumation proofs.”

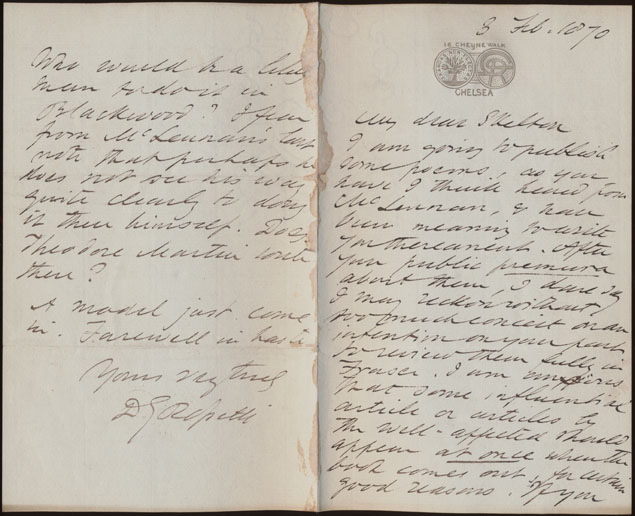

These detailed communications to fellow writer John Skelton (who used the pseudonym “Shirley”) show the care Rossetti took in getting press coverage for Poems. The first letter announces the book’s existence months in advance and requests a review, the second thanks Skelton for his favorable article, “The Poems of Dante Gabriel Rossetti,” which had just appeared in the May issue of Fraser’s magazine.

Because of delays in manufacturing the elaborate gilt-stamped binding design a handful of copies, to be sent to reviewers, were circulated pre-publication bound in plain dark blue-green cloth. This one has the ownership signature of George Lillie Craik, a publisher at Macmillan and Co., the firm that had published Christina Rossetti’s Goblin market and other poems in 1862 and The prince’s progress in 1866.

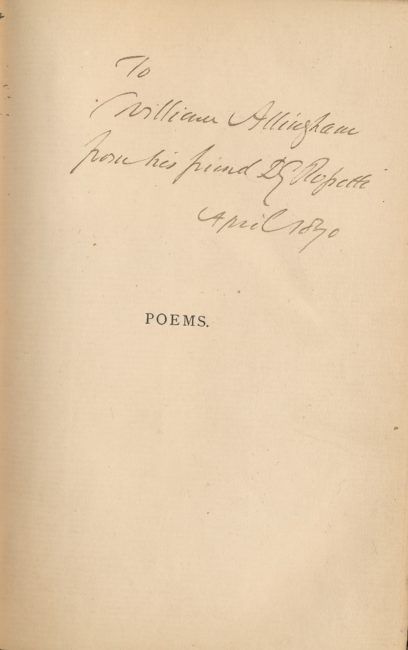

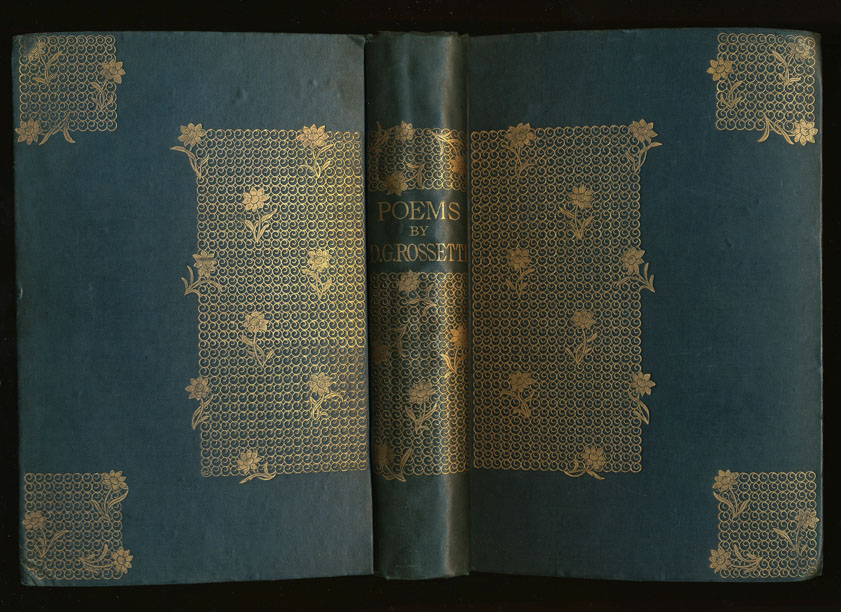

An author’s presentation copy, inscribed to William Allingham. A long-time friend and confidante (one of the few who was told of the exhumation), the Anglo-Irish poet was among those whose name appears in a list of recipients of presentation copies Rossetti sent to his publisher. This copy is in the early binding state, with eight blank leaves and publisher’s advertisements used to fill in the space created by the spine having been made too wide for the text block. The woodblock for the spine lettering and decoration was re-cut, with later versions bound without the extra padding.

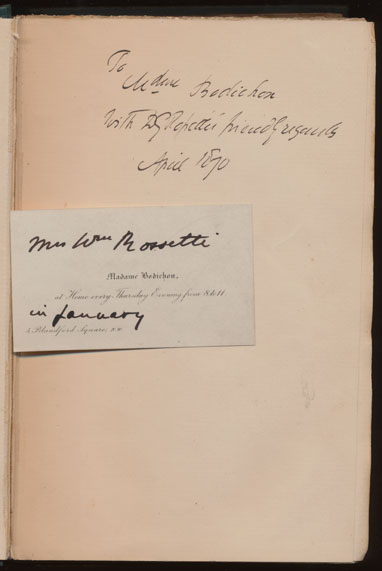

Rossetti presented this copy to the feminist Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, one of the founders of Girton College, Cambridge, and a talented landscape painter as well as a leader in the movement for women’s rights. Rossetti was staying at her country estate, Scalands Gate, in Sussex, while Poems was in final production stages. This copy is in the same early binding state as the copy inscribed to Allingham.

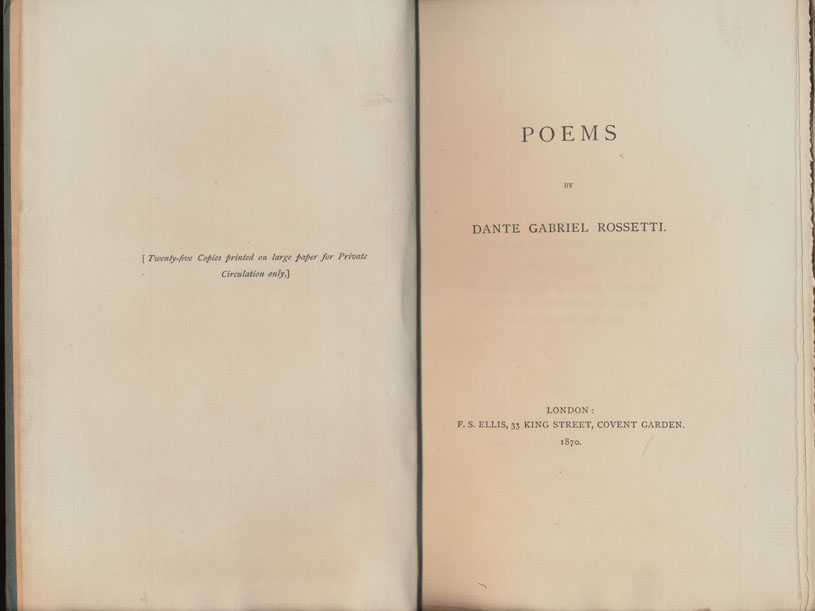

In addition to the copies bound in cloth, a small number of large paper copies were issued, printed on Whatman hand-made paper. Some of these were bound in paper-backed blue boards with a printed paper label on the spine. A limitation notice, “Twenty-five copies printed for private circulation only.” appears opposite the title-page, but as many as thirty may have been produced. At the time, such large paper copies were most unusual for volumes of verse, but Rossetti’s publisher, Frederick Ellis, was also an antiquarian bookseller who no doubt knew how to market such expensive volumes to collectors and lovers of fine books.

Rossetti also had a few copies (different sources give the number variously as six or twelve) bound in cream cloth with his cover design and with the endpapers printed in orange. These were intended as special gifts, but came too late to serve their purpose.

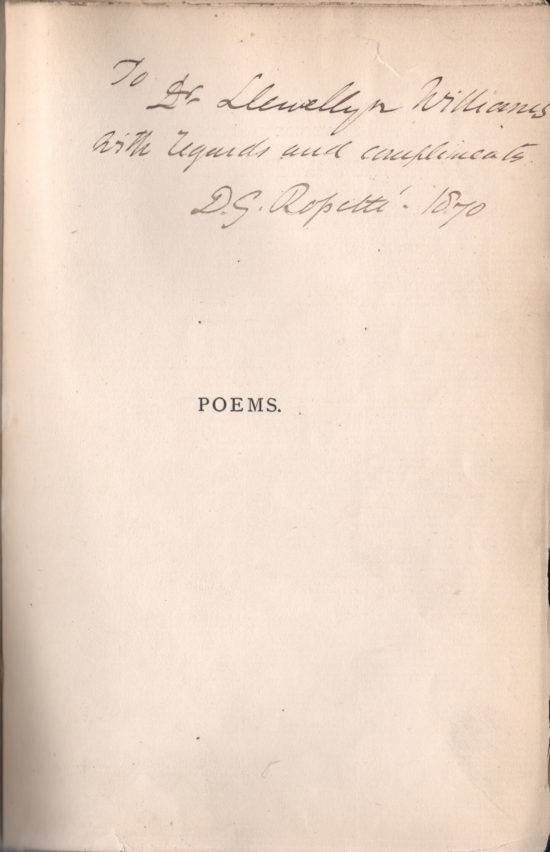

Somewhat to the author’s and publisher’s surprise, Poems sold well, with the first printing of a thousand copies exhausted in a matter of weeks. Ellis reprinted the book five times during 1870–1871, each “edition” actually having only minor changes in the text. Rossetti inscribed this third edition to Dr. Llewellyn Williams, the Home Office medical officer who attended the opening of Elizabeth Siddal’s grave and undertook the task of cleaning and disinfecting the exhumed manuscript book of verse published in Poems. On 15 October 1869, a week after the coffin was opened, Rossetti wrote to his brother, William Michael Rossetti, recording a visit to Williams to see the manuscript, noting that it was in a “disappointing state but not hopeless,” had a “dreadful smell” and a “great worm-hole” through many of the poems.

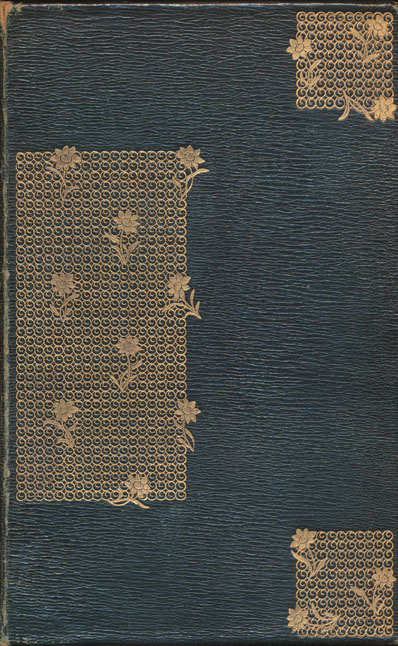

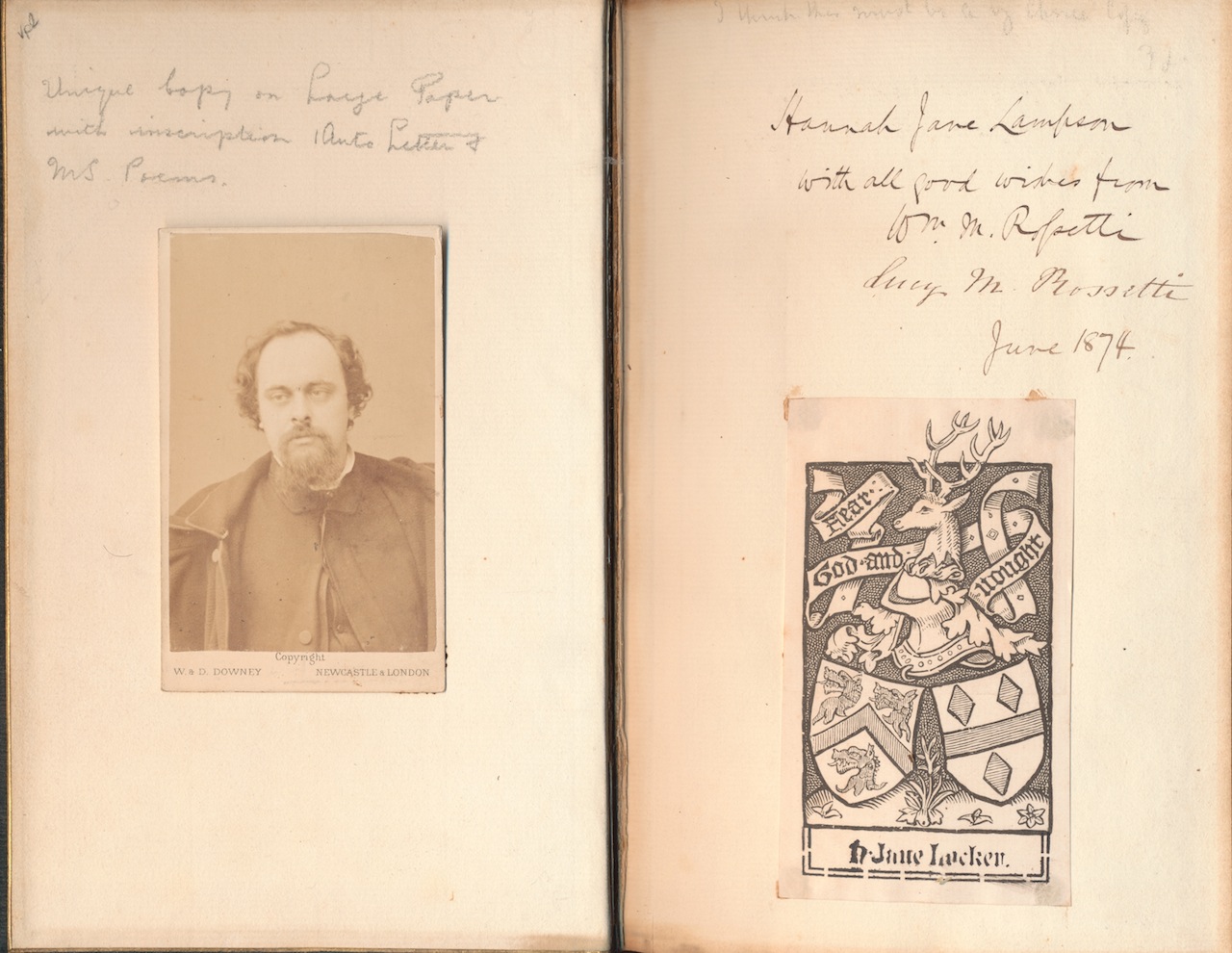

This is an unusual large paper copy, bound in morocco stamped with the design by Rossetti used for the regular clothbound version of Poems. William Michael Rossetti presented it as a wedding present to Jane Lampson, daughter of the Vermont-born proponent of the Atlantic Cable, Sir Curtis Lampson, on her marriage to Frederick Locker. Locker—who later took on the surname Locker-Lampson, was a well-connected poet and book collector, whose famous Rowfant Library (named after the couple’s country house) contained what he considered the germs of English literature. To make the gift even more special, William Michael Rossetti pasted in an original photograph of Dante Gabriel and inserted a manuscript of one of the poems and a letter from his brother to the publisher, Frederick Ellis, regarding a review by the critic Sidney Colvin; his own letter of transmittal to the Lockers states that the book is unique in having Dante Gabriel’s cover design.

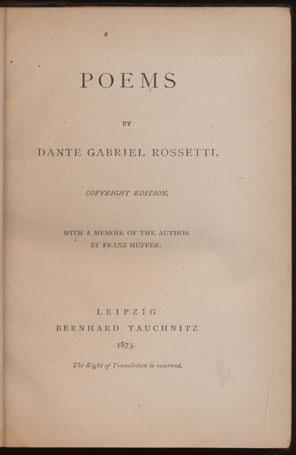

Rossetti revised the text of Poems for this 1873 edition, published by Tauchnitz as part of their large library of English-language titles sold throughout the Continent. This copy is bound in contemporary green calf—likely an author’s presentation binding—and inscribed to his close friend, Theodore Watts-Dunton, a lawyer and writer best known for his long association as the protector and housemate of the poet, Algernon Swinvunre. Watts-Dunton’s 1898 novel, Aylwin, was a fictionalized account of Rossetti.

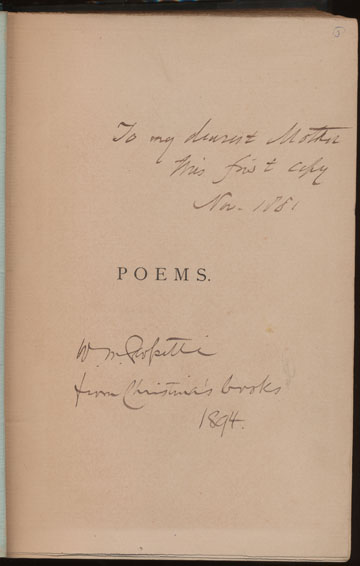

In 1881, Rossetti divided the contents of Poems into two separate works, making considerable textual alterations at the same time. Ballads and sonnets included the sonnet-sequence, “The House of Life,” which had made up the second half of the 1870 edition; Poems: a new edition contained the first printing of an additional poem, “The Bride’s Prelude.” The cover design for Poems was reused for both books and for Rossetti’s posthumous Collected works, edited by William Michael Rossetti in 1886. This is the “first copy” presented by the author to is mother, Frances Mary Lavinia Polidori Rossetti. Mrs. Rossetti is reported to have said that she wished her four talented children had less genius and more common sense.

![Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. After the French liberation of Italy. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869]. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. After the French liberation of Italy. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869].](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/rossettis-poems-in-progress/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2019/10/03-Rossetti.afterFrench.proof_.jpg)

![Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. On the site of a mulberry-tree. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869]. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. On the site of a mulberry-tree. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869].](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/rossettis-poems-in-progress/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2019/10/04-Rossetti.onsite.proof_.jpg)

![Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. Poems: privately printed. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869]. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. Poems: privately printed. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869].](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/rossettis-poems-in-progress/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2019/10/05-Rossetti.poemsprivptd.proof_.jpg)

![Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. Hand and soul. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869]. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. Hand and soul. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869].](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/rossettis-poems-in-progress/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2019/10/06-Rossett.handandsoul.jpg)

![Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. Poems by D. G. Rossetti, privately ptd, July to Decr. 1869. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869–1870]. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828-1882. Poems by D. G. Rossetti, privately ptd, July to Decr. 1869. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869–1870].](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/rossettis-poems-in-progress/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2019/10/07-Rossetti.pemsprivptdBoyd.png)