[1] Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness

Wyatt Patterson: In 1973, Barbara Ehrenreich, a journalist and feminist activist, and Deirdre English set out to expose how the Western medical establishment had betrayed women throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Feminist Press, established in 1970 at the City University of New York by Florence Howe, published this important work, which revealed that women’s illnesses had often been misdiagnosed as caused by “hysteria” or nervous conditions and dismissed. Ehrenreich and English argued that physicians had been complicit in oppression—in men’s control over women’s lives and bodies. They also addressed the impact of class and race: upper-class white women were defined as delicate and “sick,” whereas working-class women and especially Black women were dangerous and “potentially sickening to men.”

.

.

[2] Woman, Culture and Society

Matthew Mestre: This anthology helped to define the field of feminist anthropology studies, collecting some of the most significant statements produced during the period of the Second Wave. It included an essay that became a classic, “Is Female to Male as Nature Is to Culture?” by Sherry B. Ortner, but it also went beyond the conventional bounds of anthropology. Among the sixteen writers whose work was represented was Nancy Chodorow, a distinguished sociologist and later author of The Reproduction of Mothering (1978). Each contribution detailed the constructions of women in a variety of communities, recognizing these not as matters of biology, but of societies and cultures.

.

.

.

.

.

[3] Beyond the Veil

Jasper Verucci: This study, the Moroccan author’s first book, created controversy when published but has since become a classic. Mernissi analyzes the pre-Islamic social order and its dramatic restructuring under Islam while providing a new perspective on Muslim female sexuality. She argues that Muslim and non-Muslim worlds equally oppress women, but with a fundamental difference in their understandings of female sexuality. Importantly, Mernissi presents her own interpretation of Islam and finds traditional Islamists to manipulate the words of the Qur’an in ways harmful to women and men alike. This empowering text initiated Islamic feminist discussions and advocated for the inclusion of Islam in women’s liberation movements.

[4] Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape

Samantha Burke: Early in Against Our Will, Susan Brownmiller asserts that she wrote this study because she was a woman who changed her mind about rape. While some readers may assume that Brownmiller must have been a victim-survivor herself of sexual violence, she sets out to prove why that assumption, like so many others about rape, is so damaging. This was among the first books to examine the enormous social power that rapists possess, as Brownmiller reveals that rape is not an individual act or anomaly, but a political expression of violence—a crime of power that stems from a sexist culture. Brownmiller’s work helped to make rape a public concern. Because she changed her mind about rape, many readers did, too.

[5] On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose, 1966–1978

Maggie Buckridge: In this powerful volume, Adrienne Rich collects her Second Wave prose works in order to “define a female consciousness.” While best known as a lesbian poet, Rich was also a prolific and deeply influential feminist scholar, teacher, and essayist, who first identified “compulsory heterosexuality” as a form of oppression. On Lies, Secrets and Silence includes Rich’s bold exploration of topics such as motherhood, family, lesbian sexuality, race, and higher education. She engages here, too, with a range of past and present-day women writers from Anne Bradstreet and Emily Dickinson to the poet Anne Sexton. When reflecting throughout on her experiences as a woman, mother, lesbian, student, and professor, Rich brings to life the feminist principle of the personal as political.

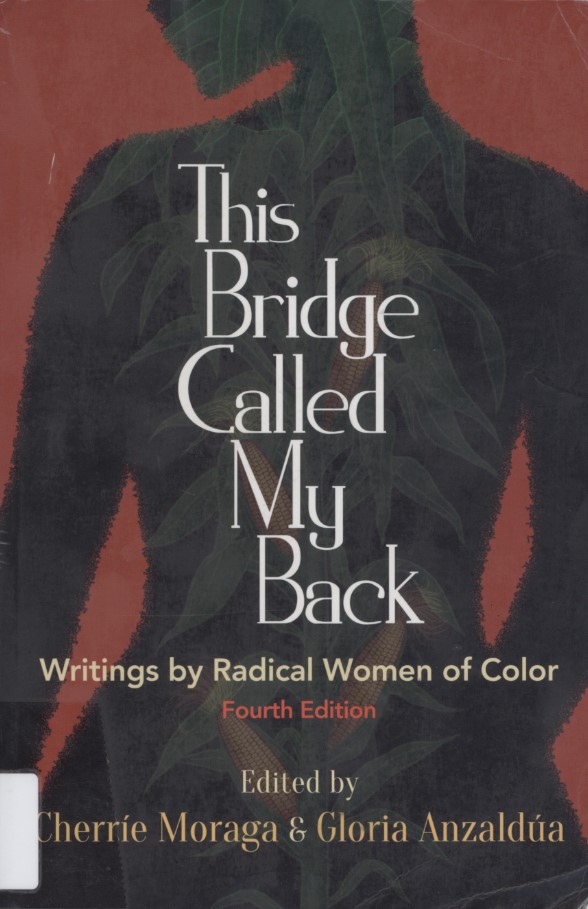

[6] This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color

Emily Gaviria: Since it appeared in 1981, this has been one of the most groundbreaking and widely read of all feminist anthologies—a foundational volume that has profoundly influenced feminist thinking, past and present. It has gone through numerous editions, but was originally published by Kitchen Table/Women of Color Press, which was established by Audre Lorde and Barbara Smith to promote radical voices. The essays and narratives in this collection include potent examples of intersectionality, written before that theory even had a name; yet they already explore how oppressions interlock and must be addressed as linked phenomena. Many of the contributions break the barriers of genre, drawing on multiple forms to examine the destructive effects of racism, colonialism, homophobia, and also sexism.

.

.

.

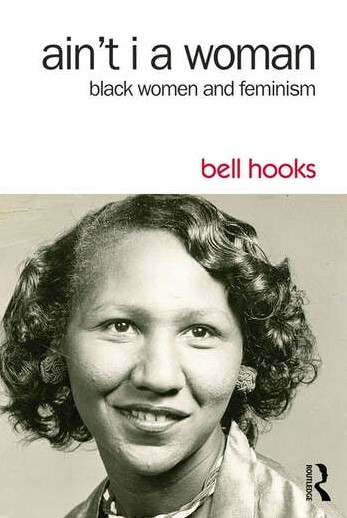

[7] Ain’t I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism

Madeline Grunsby: Writing as “bell hooks,” Gloria Watkins became one of the most important feminist theorists of the late-twentieth century, beginning with the publication of this book. Its title came from the famous challenge that Sojourner Truth posed to white feminists in 1851, when they excluded Black women from their campaign for women’s rights. In this book, hooks connects the history of slavery to present-day patriarchy, capitalism, and racism, which have all come together to negatively impact the experiences of Black women in America, whether past or present. Her goal is to create feminist theory that pays close attention to the intersections of race and gender, while reminding readers not to generalize, but instead to remember that Black women are also individuals.

.

.

.

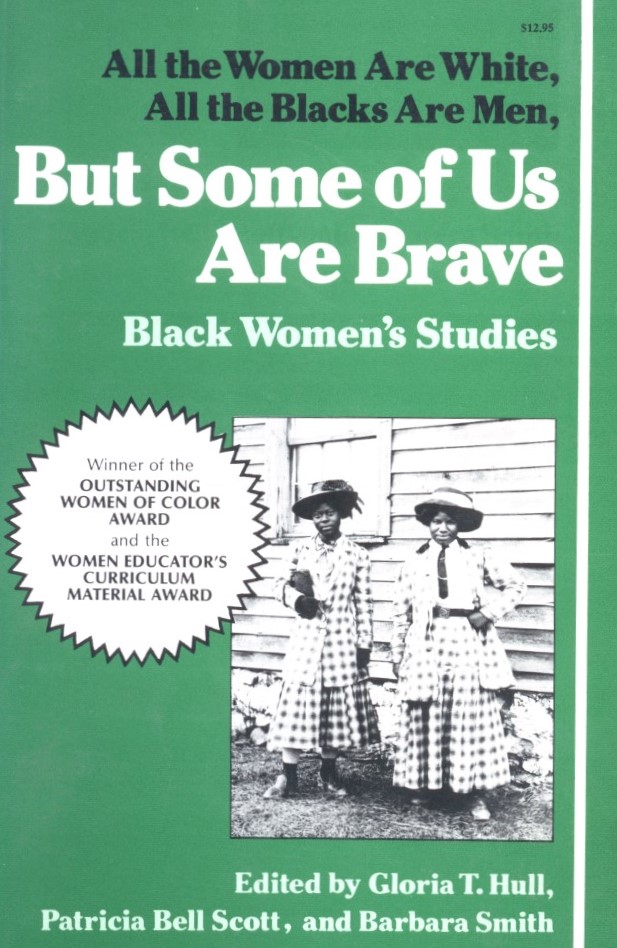

[8] All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies

Caleb Beardsley: Before this groundbreaking anthology, Black Studies disproportionately focused on Black men, while Women’s Studies was too often the study of white women, with Black women largely left on the sidelines. To right this wrong was the goal of (Akasha) Gloria T. Hull—a professor at the University of Delaware and one of the founders of its Women’s Studies program—and of her co-editors, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith. The result was a reader that became an essential resource in countless feminist classrooms, bringing to light the issues, perspectives, lived realities, problems with multiple oppression, and also literary achievements of Black women, chiefly in America, from the past through the present.

.

.

.

.

.

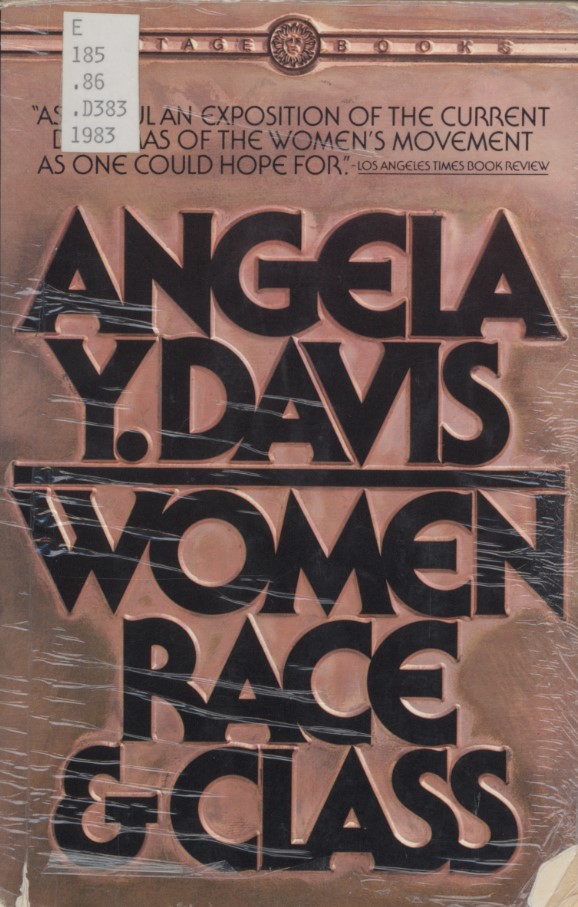

[9] Women, Race & Class

Alyssa Bergstrom: Her works have been pillars of feminist research, while Angela Davis herself has been both hated and adored because of her political activism, ever since her involvement in the early Black Power and Women’s Liberation movements. In Women, Race & Class, she critiques the history of white feminism and examines the oppression of women of color, along with Black women’s achievements, through the lens of what has come to be called intersectionality. Using the context of multiple overlapping identities. Davis became one of the first scholars to employ this type of feminist analysis, making her study groundbreaking in its time. Her interest throughout is in connecting the past with the present in order to argue for radical change.

.

.

.

.

.

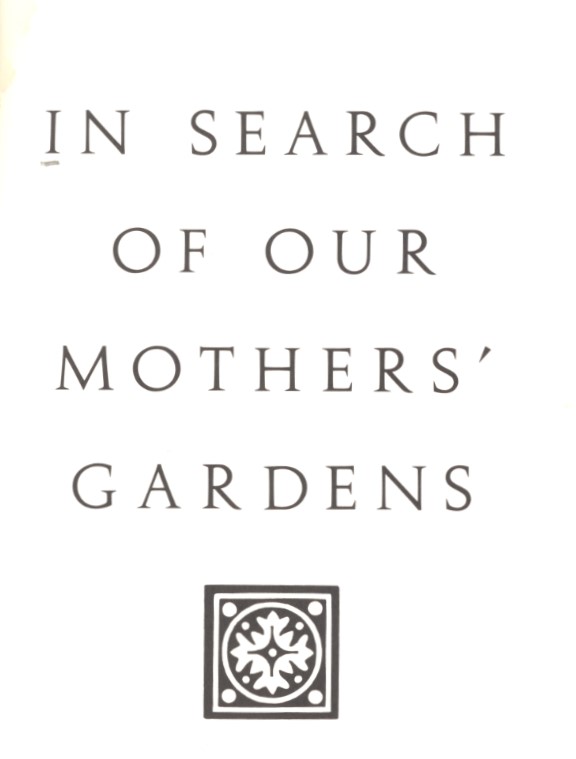

[10] In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose

Jillian Brenneman: In 1983, the same year she received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for The Color Purple, Alice Walker published this collection of her essays from 1966 to 1982. It included the title work, a tribute to earlier generations of Black women whose creativity and spirituality were suppressed, yet also expressed nonetheless through the domestic arts. She began this volume by defining a “Womanist”—a Black feminist or feminist of color—as an activist who loves both men and “other women, sexually and/or nonsexually” and is dedicated to the survival and liberation of her whole community. Her concept of “Womanism” became hugely influential as an alternative to white notions of feminism, especially in the Third Wave.