The ringing sound of an axe head pounding splints from a straight section of ash. The aromatic fragrance of sweetgrass as it is braided more quickly than the eye can see. The smooth pull of the wood’s grain as a weaver pulls a splint through her fingers. These are the sensations that accompany the weaving of ash and sweetgrass baskets. The ancestors of the Wabanaki artists in this exhibition emerged from a brown ash tree after Gloosekap (also spelled Glooskap, Gluskabe, Gloosecap, Glooscap, or Klooskap) shot an arrow into its trunk.[1] Ash and sweetgrass have sustained Wabanaki lifeways for as long as collective memory reaches back. Contemporary basket makers experiment with the properties of these two materials as part of a long continuum of creativity.

The Wabanaki Alliance

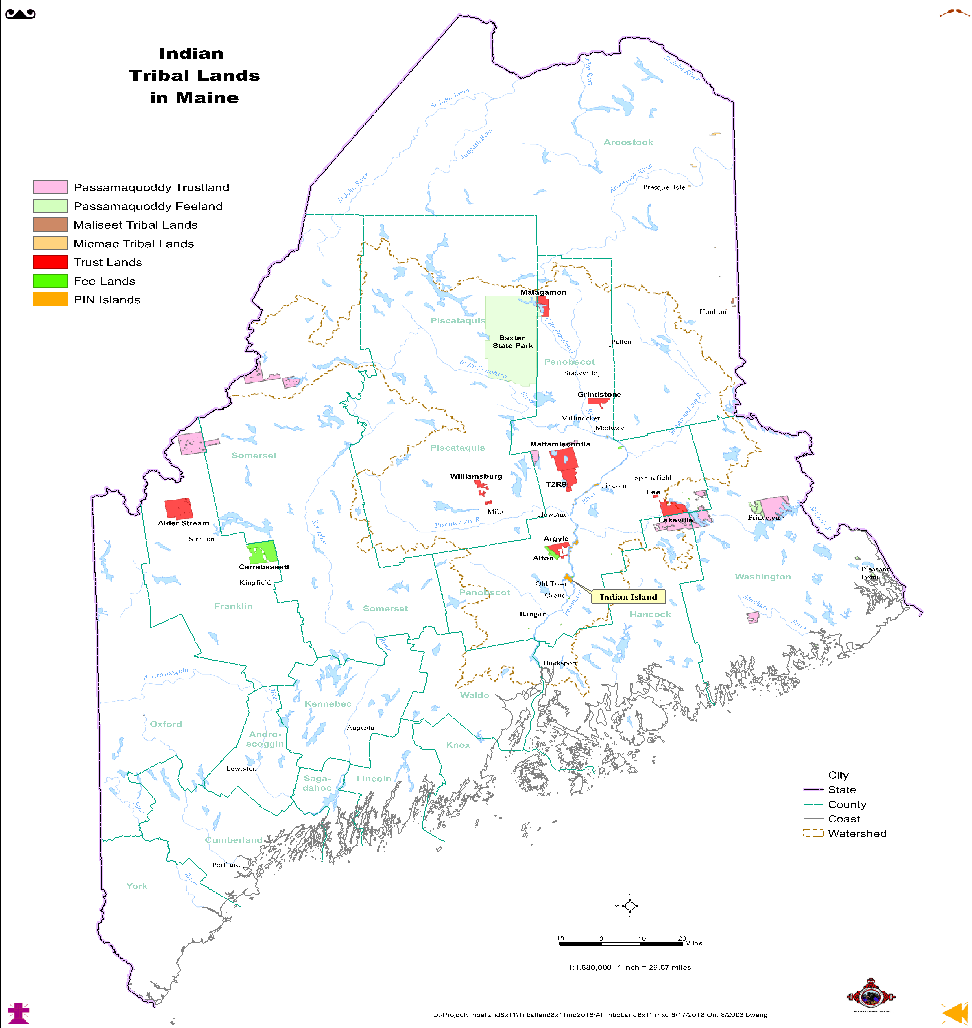

Wabanaki translates to “People of the Dawnland.” The Wabanaki have greeted the sunrise from the eastern coast of North America for at least 13,000 years, according to the archaeological record.[2] Four principal nations, the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot, formed the Wabanaki Confederacy during the late seventeenth century in response to European encroachment. Their unceded homelands stretch from the northern parts of what is now called New England through southeastern Quebec in Canada as well as the Canadian maritime territories. Today, there are four federally recognized tribes in the United States who are part of what is now the Wabanaki Alliance: the Penobscot Nation (reservation in Washington County, Maine), the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Sipayik (also known as Pleasant Point) and Indian Township (reservations in Washington County, Maine), the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians (reservation in Aroostook County, Maine), and the Mi’kmaq Nation (reservation in Aroostook County, Maine).[3]

Wabanaki cultural practices, ecological knowledge, and political systems have evolved over millennia in relationship with their environment. European colonization and the imposition of reservation systems now require communities to stay fixed in one place throughout the year. Before the last 400 years, Wabanaki bands would have traveled in response to environmental change across seasons and between years. Procedures for harvesting wood or bark, gathering sweetgrass, and digging up roots to make baskets evolved as a part of these cyclical transitions.

Making Baskets

When Fred Tomah (Houlton Band of Maliseet) started making baskets, a year passed before his uncles and grandfather taught him to weave. He had to learn how to gather materials first, starting with identifying and harvesting brown ash trees.[4] Other basket makers recount similar experiences. Wikpiyik (brown ash in Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet, known elsewhere as black ash) grows straight and tall in marshy wetlands. The name translates directly to “basket tree.”[5] Only one in twenty ash trees is suitable for making baskets. After identifying and felling a tree, the harvester cuts the trunk into 4- to 12-foot sections.[6] Once the sections have been dragged from the woods, the logs are pounded so that they separate into strips, or splints, along their annual rings. These splints, which are as long as the log, are split down further into wide standards or thinner weavers. Basket makers pass the weavers horizontally through vertical standards, which form the base and support the sides of their baskets. Many basket makers carve wooden basket forms or use forms passed down across generations to create even shapes and support straight sides in their baskets.

Fragrant welimahaskil (sweetgrass in Passamaquoddy) hides between taller stands of more brittle grass in coastal salt marshes. After picking sweetgrass one shoot at a time, harvesters must comb it clean before hanging it up to dry. Basket makers weave individual strands and braids of sweetgrass into their baskets. Both brown ash and sweetgrass are integral to contemporary Wabanaki basket making. Recently, access to these materials has come under threat. The Emerald Ash Borer, an invasive beetle that kills ash trees, reached Maine in 2018. Depleted salt marshes and changing property laws have prevented basket weavers from harvesting sweetgrass on traditional sites. To make sure that Wabanaki basket making continues, artists have driven the development of forestry practices that impede the Emerald Ash Borer and advocated for better access to ancestral sites for sweetgrass. Many have also started experimenting with other materials like basswood and cedar to ensure that no matter what happens, basket making carries on in their communities.[7]

Resurgence

The artists in this exhibition are part of a surging revival of Wabanaki basket making. The Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance (MIBA) was founded in 1993 to make sure that younger artists continued to learn the art form. The organization’s apprenticeship program, funded through the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and other organizations, has supported a new generation of artists. This online exhibition explores both the history and future of Wabanaki basket making through the baskets in the University of Delaware Museums Collections.

[1] Jennifer S. Neptune and Lisa K. Neuman, “Basketry of the Wabanaki Indians,” in Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, ed. Helaine Selin (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2015), 1.

[2] “Holding up the Sky: Wabanaki People, Culture, History & Art,” Maine Memory Network, accessed May 4, 2023, https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/2976/page/4665/display.

[3] “Wabanaki History,” Wabanaki Alliance, accessed May 4, 2023, https://wabanakialliance.com/wabanaki-history/.

[4] David Shultz, Baskets of Time: Profiles of Maine Indian Basket Makers (Kennebunkport: Home & Away Gallery, 2017), 138-139.

[5] Darren J. Ranco, “Wikpiyik: The Basket Tree,” My Maine Stories, accessed May 4, 2023, https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/2977/page/4666/display.

[6] Neptune and Neuman, “Basketry of the Wabanaki Indians," 7.

[7] Neptune and Neuman, “Basketry of the Wabanaki Indians," 9; Lisa K. Neuman, “Basketry as Economic Enterprise and Cultural Revitalization: The Case of the Wabanaki Tribes of Maine,” Wicazo Sa Review 25, no. 2 (2010): 89–106.

![Rocky Keezer (Passamaquoddy Tribe at Sipayik [or Pleasant Point], Maine, b. 1969), Natural and Purple Woven Porcupine Basket, ca. 2008, dyed and natural brown ash, sweetgrass. Interior view. Rocky Keezer (Passamaquoddy Tribe at Sipayik [or Pleasant Point], Maine, b. 1969), Natural and Purple Woven Porcupine Basket, ca. 2008, dyed and natural brown ash, sweetgrass. Interior view.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/contemporary-wabanaki-baskets/wp-content/uploads/sites/273/2023/05/keezer_purple_porcupine_interior.jpg)