Edward Everett’s oration, a lengthy history of the battle meant to underscore honors due to the dead and give meaning to their deaths, was given from memory and lasted two hours. Music preceded the program’s opening prayer, Everett’s oration, and Lincoln’s address, which was followed by more music before a final benediction. Lincoln’s “appropriate remarks” were all but buried near the end of the long program and were indeed few: a total of 272 words delivered in barely more than two minutes.

There are varying accounts about the reception of Lincoln’s speech. It happened so quickly that many may not have had the chance to process his message, though its appearance in print gave everyone the chance to ponder and appreciate his eloquence. It appeared in the national press on November 20 and is still widely circulated in varied forms, from mini- and pocket-sized books to decorative broadsides.

[Item 1] Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and Second Inaugural, texts and illustrations compiled by Charles Moore. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1927. Number 279 of 440 numbered copies. Printed at the Riverside Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

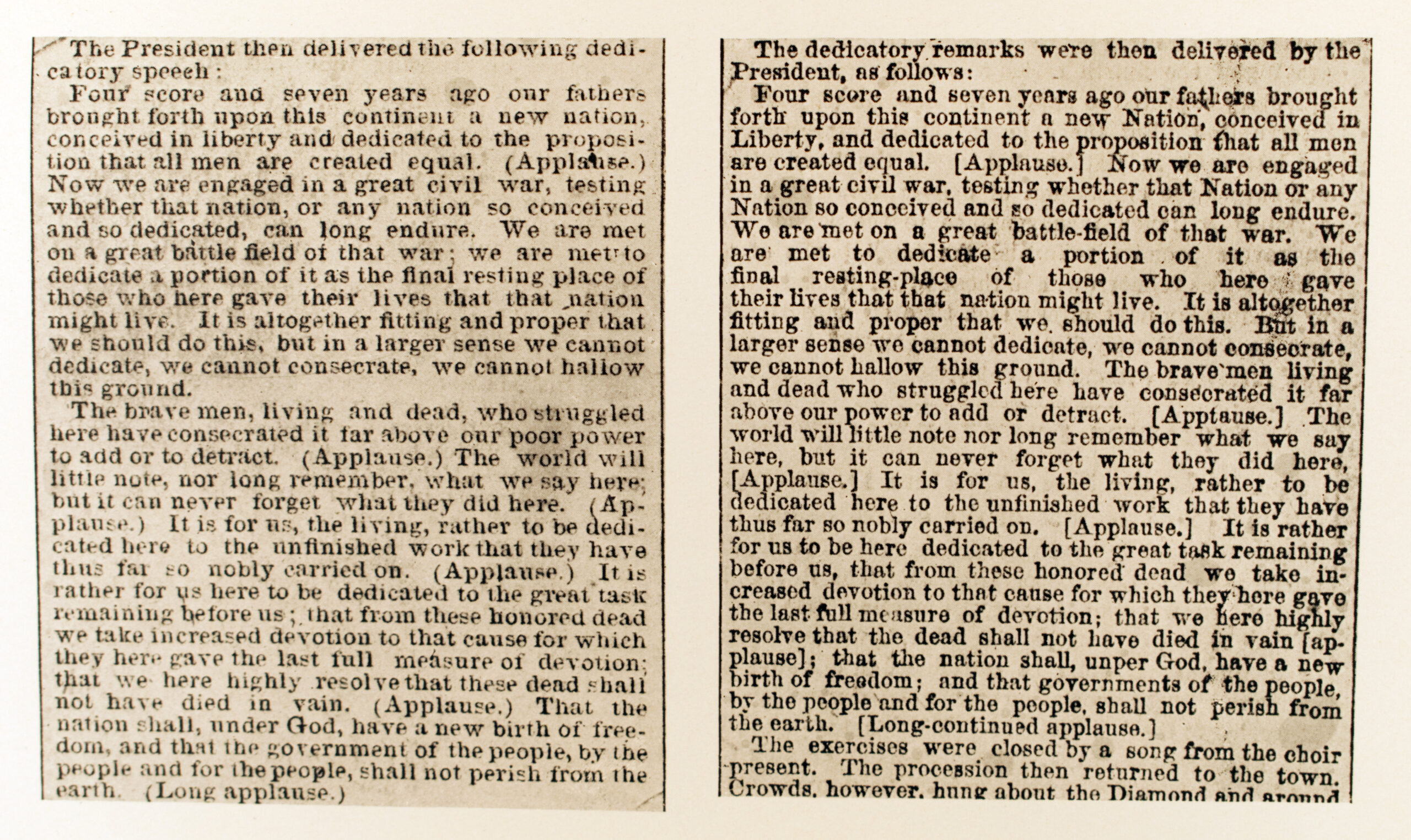

Shown are photo-facsimiles of stenographic reports of the Gettysburg Address that appeared in the Philadelphia North American and the U.S. Gazette, November 20, and the New York Tribune, November 21 (with the crowd’s applause noted).

Joseph L. Gilbert, an Associated Press reporter with shorthand skills, was seated on the speaker’s platform at Gettysburg and asked President Lincoln, immediately after he sat down, to let him see Lincoln's copy of the speech for comparison with his own transcription. In addition to Gilbert's first-hand capture of the speech, which appeared in print the next day, newspapers noted the five audience responses of “applause” in the published account of the Address (including the final “long continued applause”).

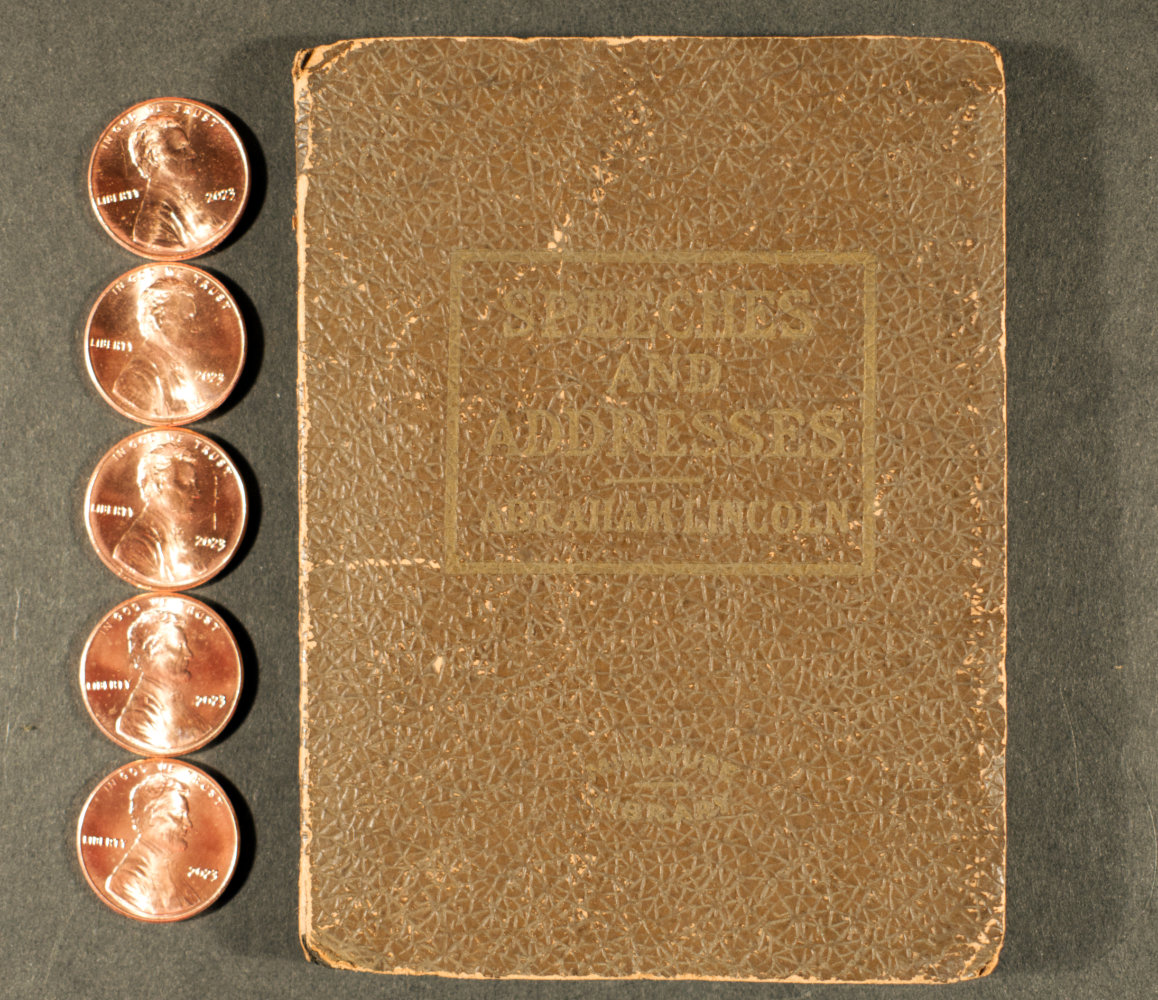

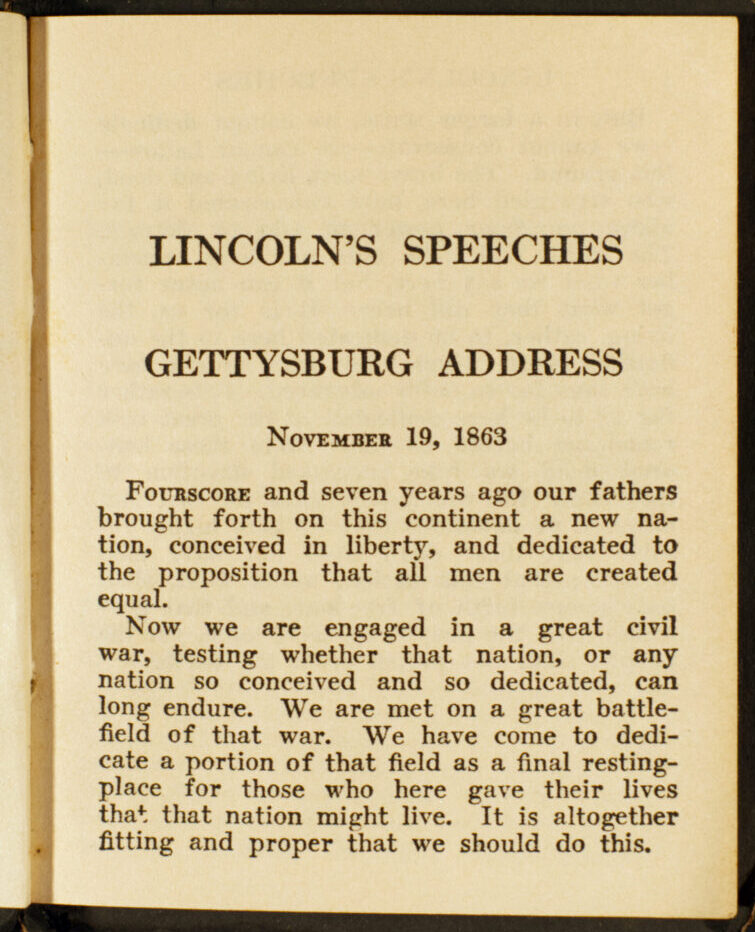

[Item 2] Speeches and Addresses of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Little Leather Library Corporation, undated.

This pocket book is four inches in height.

[Item 3] Addresses of Abraham Lincoln. Kingsport, Tennessee: Training Division, Kingsport Press, 1929.

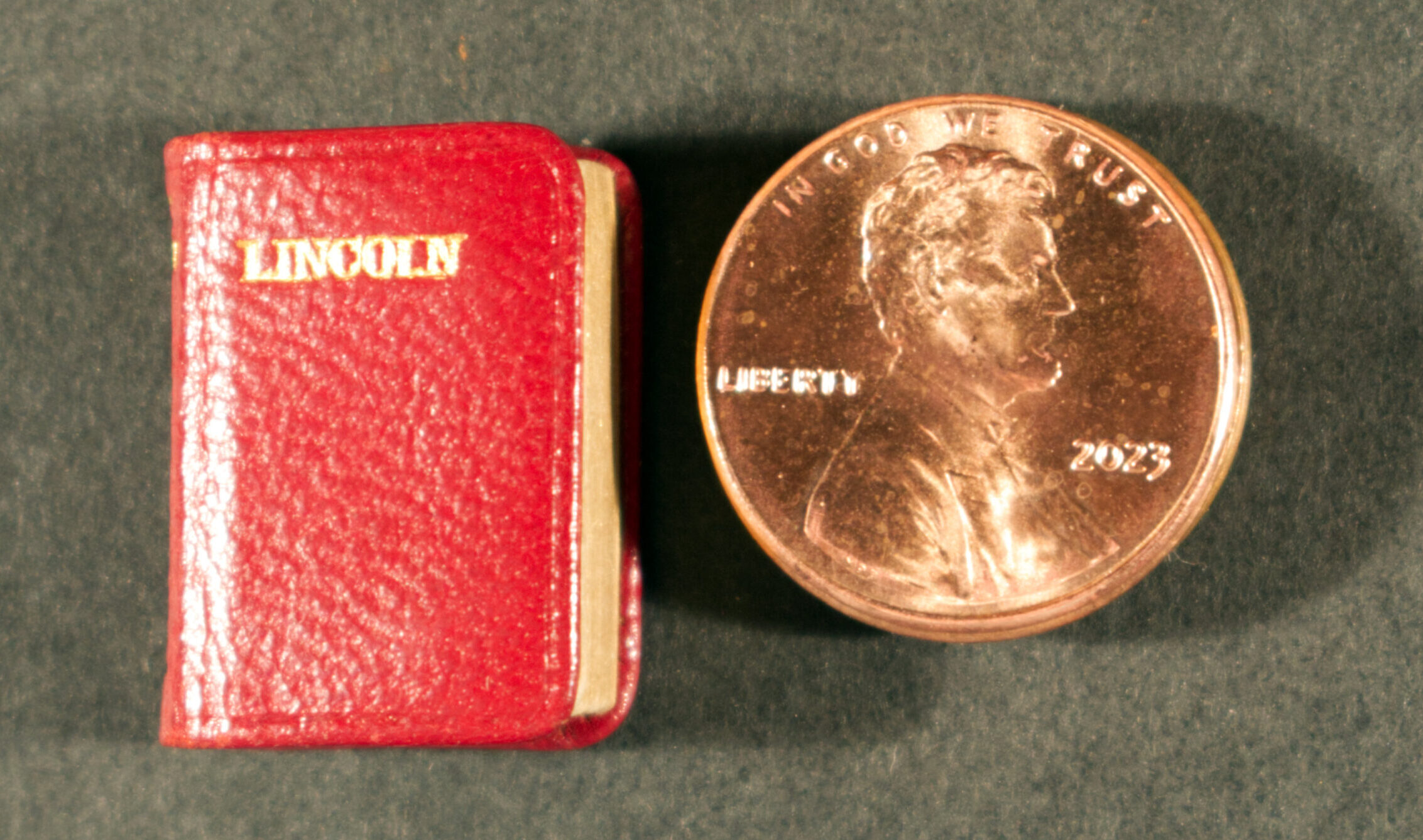

Shown with a 2023 Lincoln penny, this miniature book is 2 cm in height.

[Item 4]The Gettysburg Address [broadside]. A & G Mungo, 1926. New York: the Society of Fine Arts, copyright 1927.

This embossed color halftone print with gold metallic ink is a 1927 edition of the original illuminated manuscript of Lincoln’s famous address, created by Antonio Mungo and Giuseppe Mungo in 1926. The Mungos, on behalf of the Italian Republican League of New York, presented the original manuscript to President Calvin Coolidge on Lincoln’s birthday, February 12, 1927.

Manuscripts of the speech

Much has been written about Lincoln’s handwritten original drafts and copies of his famous address: when and where he wrote his speech, the revisions he made, when and for whom he made later copies, and where these manuscripts are now.

[Item 5] Andrews, Mary Raymond Shipman. The Perfect Tribute. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1918.

Mary Raymond Shipman Andrews, a Southern-born author of boys' books and popular contributor to Scribner's Magazine, is responsible for the myth that President Lincoln drafted his speech on a scrap of paper discarded by Secretary of State William Seward aboard the train bound for Gettysburg on November 18. Her short story, first published in Scribner's in 1906, placed Lincoln at the bedside of a dying Confederate soldier at a prison hospital in Washington, the day after he returned from Gettysburg. Unaware of who Lincoln was, the soldier confessed his admiration for the speech as published in the morning's paper, in spite of his commitment to the "other side." That Lincoln could be a partisan without bitterness in his address made the soldier feel "not Northern or Southern, but American." This sentimental fiction colored the facts about when Lincoln wrote his address for a generation of American school children, but also reflects the growing stature of the Gettysburg Address as a great American speech.

[Item 6] Madigan, Thomas F. A Few Appropriate Remarks by Abraham Lincoln: being the story of the Gettysburg Address with particular reference to the manuscript thereof. New York: Privately printed, 1931.

“This brochure is limited to 150 copies especially printed for guests at the luncheon commemorating the birthday of Abraham Lincoln by the trustees of Lincoln Memorial University at the Mayflower Hotel, Washington, D.C., February 12, 1931.

This copy of the address was handwritten by President Lincoln on January 30, 1864, at the request of Edward Everett, on behalf of Mrs. Hamilton Fish (the governor’s wife), who was head of the Ladies Committee of the Metropolitan Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Fair in New York. The phrase “under God,” which was inserted above a caret in an earlier version, appears in the text for the first time. Known as “the Everett copy,” this manuscript is in the Illinois State Historical Library in Springfield.

In February 1913, for the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, Senator Elihu Root introduced a resolution to Congress directing the Library Committee of the Lincoln Memorial Commission (first chaired by President William Taft) to determine the correct version of the Address to be used on such public memorials. In consultation with Robert Todd Lincoln, the “standard” was determined to be the version Lincoln made on March 11, 1864, for the benefit of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Fair in Baltimore, which appeared in Autograph Leaves from our Country’s Authors.

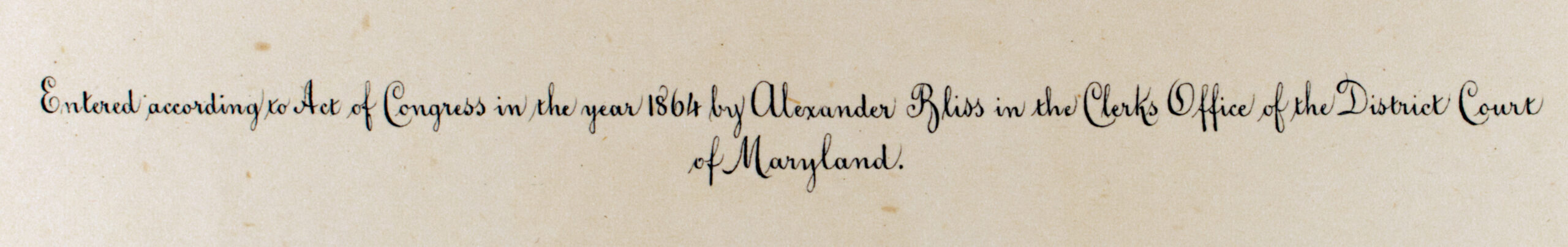

[Item 7] Kennedy, John Pendleton, and Alexander Bliss. Autograph Leaves of Our Country’s Authors. Baltimore: Cushings & Bailey, 1864. A.Hoen & Co. Lithographers, Baltimore. Entered according to an Act of Congress in the year 1864 by Alexander Bliss.

Alexander Bliss and John Kennedy created Autograph Leaves of our Country's Authors, a lithographed volume of facsimiles, as a fundraiser for the aid of soldiers and their families in Baltimore. At the request of statesman and historian George Bancroft (stepfather to Alexander Bliss), Lincoln prepared a copy of his address in February 1864 but Bliss had to ask for a separate additional copy to meet the publishing specifications of the editor, John Kennedy. Lincoln’s Address was the second manuscript in the volume, following Francis Scott Key’s national anthem.

The second copy Lincoln made for Autograph Leaves–including a title, date, margin settings and his signature, all to the editor’s specifications–has become known as the Bliss copy and is widely reproduced, as shown here. It contains Lincoln’s last known revision and is accepted as “the standard version.” The Bliss copy is on display in the Lincoln Room at the White House.

[Item 8] Tausek, Joseph. The True Story of the Gettysburg Address. New York: L. MacVeagh, the Dial Press, 1933.

[Item 9] Bullard, F. Lauriston (Frederic Lauriston). “A Few Appropriate Remarks”: Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Harrogate, Tennessee: Dept. of Lincolniana, Lincoln Memorial University, 1944. Printed at the Press of Archer & Smith, Knoxville, Tennessee. This book is limited to 250 copies, of which this is number 77. Signed by the author.

[Item 10] Wills, Garry. Lincoln at Gettysburg : the words that remade America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

Edward Everett immediately appreciated the significance of Lincoln’s efficiency and eloquence in putting the war and the soldiers’ sacrifice in perspective. He wrote to the President on November 20, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.” Ever since, Lincoln’s artistry and effectiveness has been analyzed and studied for its style and content. Garry Wills’s best-selling Lincoln at Gettysburg explores the enduring appeal of this most famous of American speeches, a true pinnacle of rhetoric.

[Item 11] Carbonell, John. The Early Printings of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and What They Reveal About His Spoken Words. First edition. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2008.

![The Gettysburg Address [broadside]. A & G Mungo, 1926. New York: the Society of Fine Arts, copyright 1927. The Gettysburg Address [broadside]. A & G Mungo, 1926. New York: the Society of Fine Arts, copyright 1927.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/gettysburg-2023/wp-content/uploads/sites/274/2023/09/3-speech-framed-scaled.jpg)

![The Gettysburg Address [broadside]. A & G Mungo, 1926. New York: the Society of Fine Arts, copyright 1927. The Gettysburg Address [broadside]. A & G Mungo, 1926. New York: the Society of Fine Arts, copyright 1927.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/gettysburg-2023/wp-content/uploads/sites/274/2023/09/3-speech-closeup-scaled.jpg)