With repetition the mind recalls images and the muscles of the hand remember gestures; confident, flowing lines communicate a surety in practiced motions. Muscle memory is created by the act of drawing, therefore, the act itself becomes integrated with the mental process of remembering. Human memory is susceptible to degradation and alteration. The acquisition of knowledge through sketching, coupled with the mnemonic aid of the paper or sketchpad, preserves memories and enhances recall. Emotional or personal involvement can also serve to sustain a memory over time. Memory is not a purely mental process, but a physical process. The artist’s body repeatedly channels the movement of her subject through the arm and the hand onto the page, until the hand can perform those movements even in the absence of that subject.

Abraham Walkowitz encountered Isadora Duncan, a pioneer of modern dance, at a performance in a private salon in 1907. Like Isadora, he stood at the threshold of the modern art movement, where formal representation began to give way to movements like Fauvism and Impressionism. Isadora’s powerful presence and unique dance style effected the artist profoundly. He sketched Isadora and her pupils in her studio, attended her shows, and produced thousands of images of the dancer throughout the following decades. "Isadora was my strongest weakness,” he wrote. “She was like music. When she moved it was like the sound of violins." If Duncan was music, Walkowitz’s repeated drawing was akin to a musician practicing scales. It became a bodily practice of channeling her movement through his body and onto the paper. His depictions are stripped down to an outline, details such as Duncan’s face omitted to emphasize the grace of her movement. The massiveness of her form fills the page to the edges, much like her presence filled the stage, gauzy washes of color accentuating the flow of fabric around her but not obscuring her body.

Faint pencil lines can be detected under some of Walkowitz’s pen and watercolor sketches, their ghostly energy adding a lively quality to each image. Sometimes graphite was even a later addition to the work. In 1915, Walkowitz was seen in a public park selling small ink sketches of Duncan that he created on the spot. Eight years after their meeting, the memory of Isadora’s movement and her form had (if not before) become embedded in Walkowitz’s sketching hand.

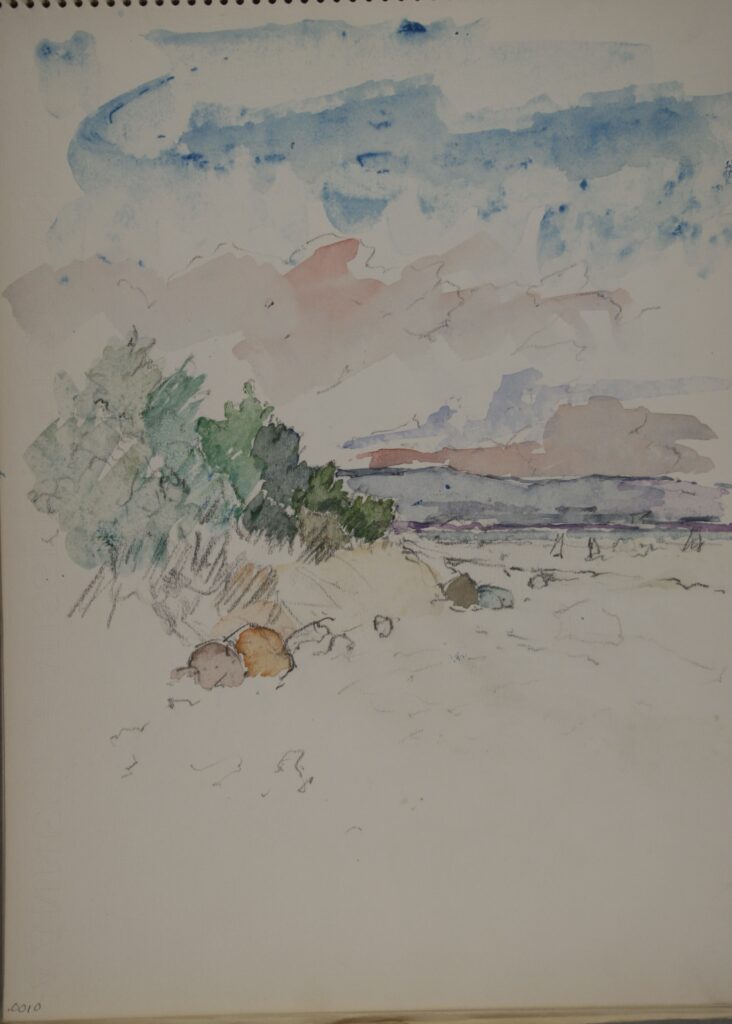

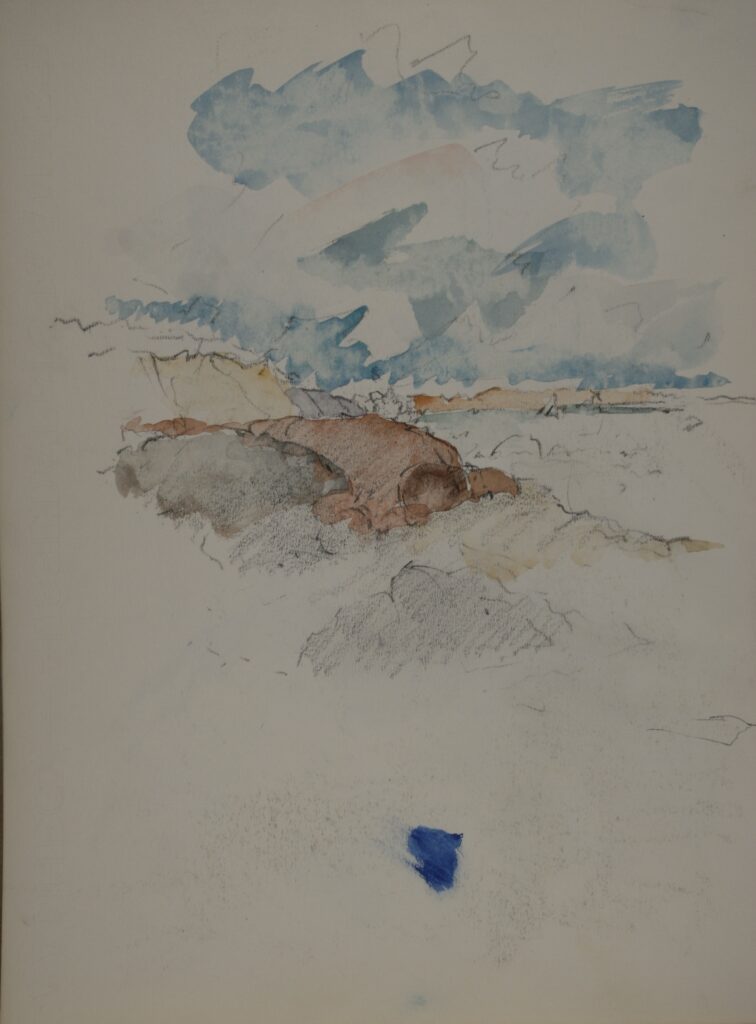

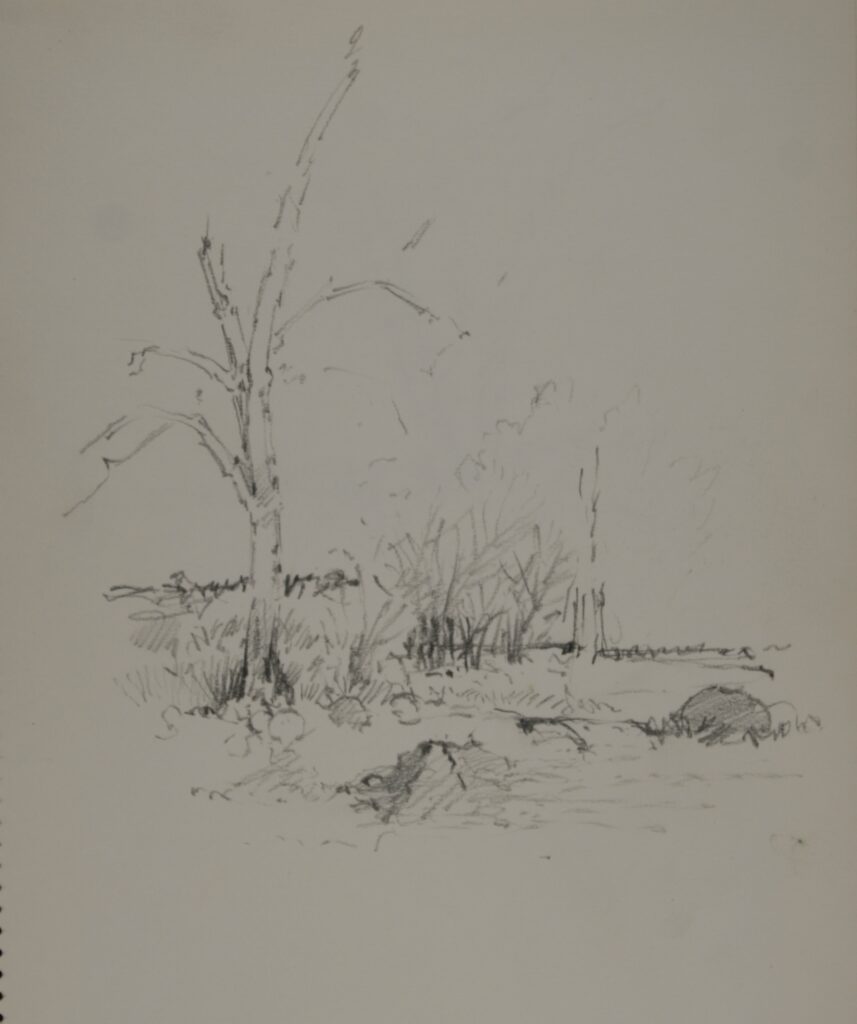

In the course of his long career, John Edward Heliker explored several styles, from Social Realism to biomorphic Surrealism, from structural Cézanne-esque abstraction, to a gestural painting style in response to Abstract Expressionism. Though his artistic pursuits took him as far as Rome and the coast of Amalfi, Heliker’s nostalgia for New England brought him to Great Cranberry Island, Maine in 1951.

For the next fifty years, Heliker filled his sketchbooks with drawings and watercolors of coastal Maine, but he did not consult them directly for any of his finished oil paintings. Like many abstract expressionists at the time, Heliker did not make studies for his final pieces, but rather worked out compositions directly on canvas. Nevertheless, Heliker never considered drawing as secondary to painting. He wrote, “It is a very intense part of my work. For me, drawing is almost a daily experience – a means of exploring my ideas and giving structure to them.”

For Heliker, pencil, charcoal, crayon, or pen was partner to building structure with color. After mixing and testing directly on the paper of the sketchbook, he added daubs of watercolor, developing volume and building the character of his subject. The repeated observation of the coastline, embedded in long-term and muscle memory, was often recalled and expressed through his very different oil painting style.

![Abraham Walkowitz (American, 1878-1965), [Isadora Duncan Study 01], 20th c., ink, watercolor, graphite. Museums Collections, Gift of Ms. Virginia Zabriskie.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/personal-pages-to-public-spaces/wp-content/uploads/sites/251/2021/11/walkowitz_isadora_01-823x1024.jpg)

![Abraham Walkowitz (American, 1878-1965), [Isadora Duncan Study 02], 20th c., ink, watercolor, graphite. Museums Collections, Gift of Ms. Virginia Zabriskie.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/personal-pages-to-public-spaces/wp-content/uploads/sites/251/2021/11/walkowitz_isadora_02-695x1024.jpg)

![Abraham Walkowitz (American, 1878-1965), [Isadora Duncan Study 03], 20th c., ink, watercolor, graphite. Museums Collections, Gift of Ms. Virginia Zabriskie.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/personal-pages-to-public-spaces/wp-content/uploads/sites/251/2021/11/walkowitz_isadora_03-839x1024.jpg)

![Abraham Walkowitz (American, 1878-1965), [Isadora Duncan Study 04], 20th c., ink, watercolor, graphite. Museums Collections, Gift of Ms. Virginia Zabriskie.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/personal-pages-to-public-spaces/wp-content/uploads/sites/251/2021/11/walkowitz_isadora_04-809x1024.jpg)

![Abraham Walkowitz (American, 1878-1965), [Isadora Duncan Study 05], 20th c., ink, watercolor, graphite. Museums Collections, Gift of Ms. Virginia Zabriskie.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/personal-pages-to-public-spaces/wp-content/uploads/sites/251/2021/11/walkowitz_isadora_05-671x1024.jpg)

![John Edward Heliker (American, 1909-2000), [<i>Color Tests</i>], n.d., watercolor. Museums Collections, Gift of Heliker LaHotan Foundation John Edward Heliker (American, 1909-2000), [<i>Color Tests</i>], n.d., watercolor. Museums Collections, Gift of Heliker LaHotan Foundation](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/personal-pages-to-public-spaces/wp-content/uploads/sites/251/2021/11/heliker_color_tests.jpg)