When the Pictorialist movement emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, photography was still relatively new. Invented in the 1830s, photography had developed a reputation among many people as something that was mechanical and commercial. The Pictorialists, in contrast, aimed to show that photography could be intricately crafted and thought provoking. Further, they demonstrated that the hand and eye of the photographer could be discerned in photographic work, with each photograph tied to the sensibility of a unique creator. In short, Pictorialists were determined to reveal photography as art.

Pictorialists produced their works using elaborate and experimental processes, meant to emphasize the skill and inventiveness of the practitioner, and they often worked with complicated chemicals and special papers. Beyond technical intricacy, some hallmarks of Pictorialism include the frequent use of soft focus, the strategic use of depth-of-field, atmospheric lighting, and carefully composed subjects (sometimes with a narrative aspect), all of which lend a painterly air to the photographs associated with the movement.

Photographers’ Collectives

Many Pictorialists in Europe and the United States participated in collectives, and the most famous of these was the Photo-Secession centered in New York. Alfred Stieglitz founded the Photo-Secession in 1902, and he explained, “Its aim is loosely to hold together those Americans devoted to pictorial photography in their endeavor to compel its recognition, not as the handmaiden of art, but as a distinctive medium of individual expression.”*

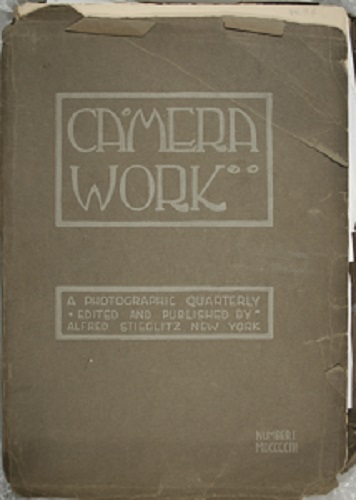

To promote the work of the Photo-Secession, Stieglitz published the journal Camera Work, which circulated high quality reproductions (usually using photogravure and halftone techniques) of Pictorialist photographs, as well as essays about photography and other cultural trends. Camera Work ran from 1903 to 1917 and was the successor to Stieglitz’s earlier photography journal, Camera Notes. The publication for the Camera Club of New York, Camera Notes ran from 1897-1903 and also featured Pictorialists.

This online exhibition explores works by many of the women who were included in one or both of these esteemed photography journals: Gertrude Käsebier, Sarah Choate Sears, Eva Watson-Schütze, Alice Boughton, and Mary Devens. All of these pioneering female photographers had their works published alongside examples by their colleagues such as Stieglitz, Eduard Steichen, George Seeley, Clarence H. White, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and many others.

*Alfred Stieglitz, “The Photo-Secession,” in Bausch and Lomb Lens Souvenir. Rochester, New York: Bausch and Lomb Optical, 1903.