In late spring, an ancient phenomenon plays out across the beaches of Delaware. Gathered by the tides, the spectacular mass mating ritual of a primeval arthropod called the horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) takes place along the Delaware Bayshore. Kitt’s Hummock, Slaughter Beach, Port Mahon, and Pickering Beach are just a few sites that host throngs of horseshoe crabs, which are more closely related to scorpions or spiders than crabs, in their highest known concentration. They are joined by a multitude of wading shorebirds, dashing through the waves to gorge on the horseshoe crabs’ tiny green eggs. Iconic among them is the red knot (Calidris canutus), a robin-sized shorebird recently designated as threatened under the Endangered Species Act and known for being one of the longest-distance migrants in the animal kingdom. Delaware’s beaches provide a crucial stopover point during the red knot’s journey, which brings them from the tip of South America to their breeding grounds in the Arctic. It is estimated that nearly 90 percent of the entire population of the Red Knot subspecies C. c. rufa can be present on the bay in a single day. The Delaware Bayshore, protected by the Coastal Zone Act, provides an internationally renowned stage for this fascinating relationship.

Since the 1980s, the red knot’s population has fallen by about 75%. This has been due in part to sea-level rise and coastal development, which shrink the shorebirds’ wintering and migratory habitat. An even larger factor, however, has been the declining population of horseshoe crabs, a popular bait harvested by coastal watermen, on which red knots and other migratory birds depend to provide sustenance for their arduous journey.

A unique feature of the horseshoe crab is its striking blue blood. Its exceptional clotting powers and hypersensitivity to microbial enemies contribute to the horseshoe crabs’ incredible resilience and evolutionary endurance. Its clotting agent lysate is used to test intravenous drugs for bacteria – per FDA regulation, no IV drug reaches the market without being tested on horseshoe crab blood. Pharmaceutical demand for the blood has created a multimillion dollar industry – one quart can sell for upwards of $15,000. Fortunately, a “bleed and release” technique has been developed allowing the horseshoe crabs to be returned to the wild. This coupled with stricter regulations on the harvesting of horseshoe crabs and the development of synthetic bait alternatives have aided attempts to restore the population.

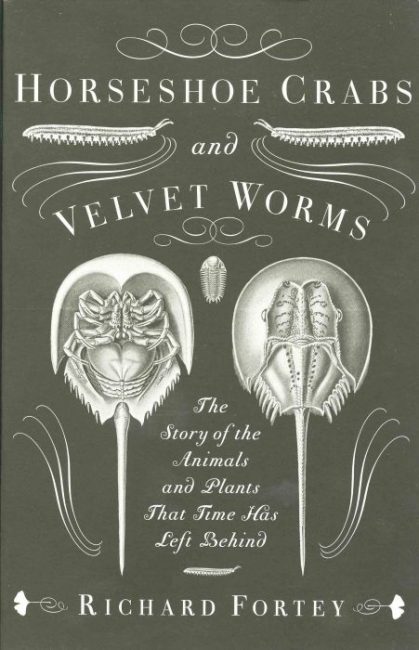

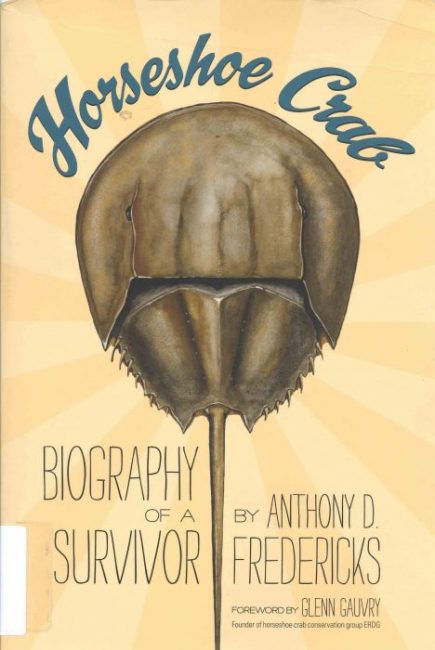

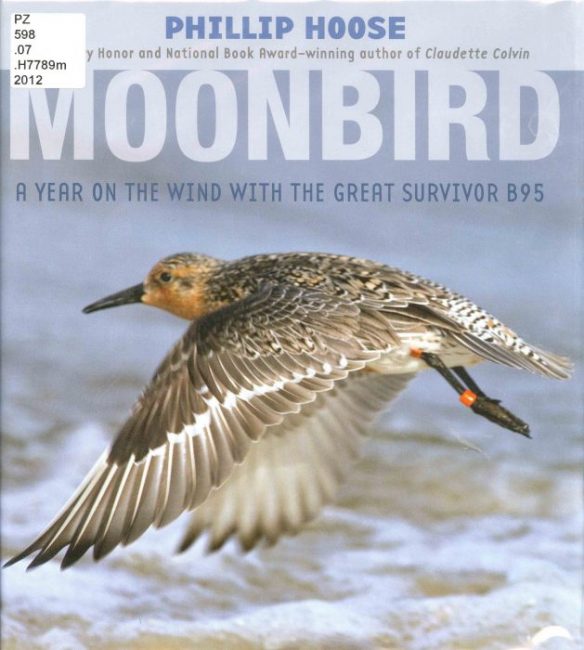

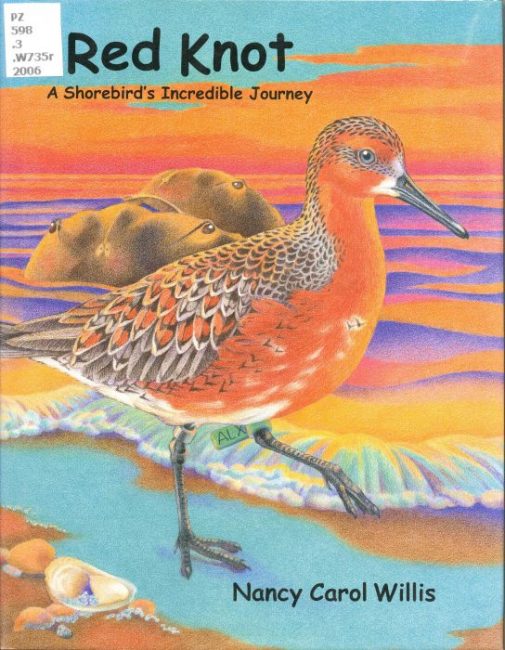

Delawareans celebrate the unique relationship between the horseshoe crab and red knot at local festivals and in children’s literature. One knot in particular, Moonbird or “B95”, was captured and banded in 1995 and spotted again as recently as 2014 – logging enough mileage to travel the equivalent distance between Earth and the moon and more than halfway back. This case highlights some of the works created for juvenile audiences that explore the phenomenon, as well as books devoted to unveiling the 350 million-year-old mysteries of the horseshoe crab.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Shuster, C. N., Barlow, R. B., & Brockmann, H. J. (2003). The American horseshoe crab. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sargent, W. (2002). Crab wars: A tale of horseshoe crabs, bioterrorism, and human health. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England.

Fredericks, A. D. (2012). Horseshoe crab: Biography of a survivor. Washington, D.C: Ruka Press.