Everyone needs containers, and several objects in this cabinet serve that function very well. There are, however, things fitting the title’s description that do not or are not meant for storage at all.

Beryl (emerald) bowl

Takovvaya River emerald deposit, Urals, Russia

1 3/4 x 2 inches

Estate of Irénée du Pont

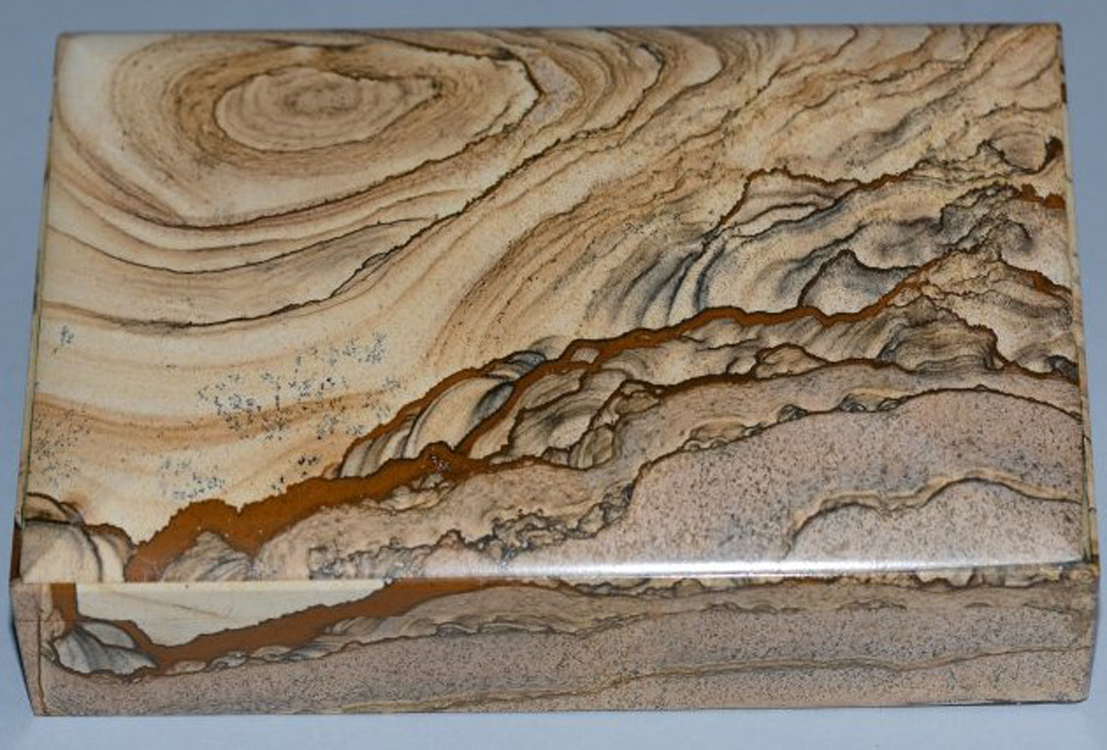

Picture Jasper box

Material from Biggs, Oregon

4 x 6 x 1 1/4 inches

Unknown Maker

Quechua Highlands, Peru

Coca Gourd, early 20th century

Gourd, bone, 5 1/4 inches long

Gift of Dr. & Mrs. Russell J. Seibert

Chewing coca leaves is common in indigenous communities across the central Andean region like the highlands of Argentina, Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru. There the cultivation and consumption of coca is a part of each nation’s culture and is an important part of traditions such as funerals. This gourd has traces of the alkaline powdered substance called lime (not to be confused with the green fruit) still visible inside. The powder is created by burning and refining quinoa leaves, and is added to the coca to soften its astringent qualities. Placing the powder inside the “chew” creates a chemical barrier so the corrosive coca does not come directly in contact with the gums and cheek.

Unknown Artist

Japan

Three Case Inro, late 19th or early 20th century

Lacquered wood, 4 x 2 7/8 inches

Gift of William M. Donaldson

This Japanese inro was used to store medicine tablets inside three chambers. Each section has a small oval receptacle. Silk cord is woven through holes on each side of the box allowing each section to be slid open, then retightened to keep the box firmly closed. This inro would be suspended on a decorative netsuke attached to the obi (sash) of the kimono. The inro was, and is, one of the most popular forms of personal lacquerware.

Unknown Artist

Egypt

Ichneumon and Sarcophagus, 600-300 BCE

Bronze, wood

4 1/8 x 1 1/2 x 1/2 inches (ichneumon); 2 x 3 3/8 x 5 1/4 inches (box)

Gift of Julius Carlebach

An ichneumon is an Egyptian mongoose, which is considered a protector of the blind and a defender against deadly snakes and evil forces. The animal is attached into holes in the lid with protrusions, called tangs, beneath its feet. The sloping tail prevents the lid from being slid open, securing the mummified relic of the ichneumon, which is no longer inside.

Unknown Artist

Japan

Shibayama Smoker’s Companion Tobacco Box, likely Meiji Period, 1868-1912

Lacquered wood, silver, gold and natural inlays, 8 1/2 x 6 inches

Donor Unknown

The lacquer inlay art form known as Shibayama is named after an area in Japan within the present-day Chiba prefecture. Created by Ōnoki Senzō, an Edo haberdasher who lived during the An’ei era (1772-1781), Shibayama inlay is unique in that it is raised in relief on the surface instead of being flush with it. From the 8th century onward, Japanese artisans perfected the practice of sprinkling gold and other pigment-producing materials into the wet lacquer, a technique known as maki-e. Sometimes gold was polished until it glowed, and other times it appeared in relief to give lacquerware dimension. These characteristics are demonstrated to their fullest on this tobacco box. The silver butterfly drawer pulls, resting hooks for the pipe, tobacco humidor, and brazier lid are intact on this box. The only missing portions are the silver carrying handle and the interior cup of the brazier.

Unknown Artist

Pre-dynastic Egypt

Shoulder Handled Jar, 3600-3200 BCE

Alabaster, 4 7/8 inches high x 2 7/8 inches diameter (of opening)

Gift of Mr. Leonard Epstein

Ubiquitous in early Egypt, these jars held mixtures used in the preparation and embalming of mummies. They were also used to store ointments or perfumes used in everyday life. Jars were formed from the stone using flint tools to roughly shape the vase, then polished with a harder stone, and finally smoothed using emery or carborundum sands. Interiors of such jars were hollowed out using drills. The drills were usually made of hollow tubular copper attached to a wooden shaft or a stone drill bit, which were rotated vertically between the palms of the hands. The drills have not survived, but parts of vase-making tool kits have been found at tomb sites.

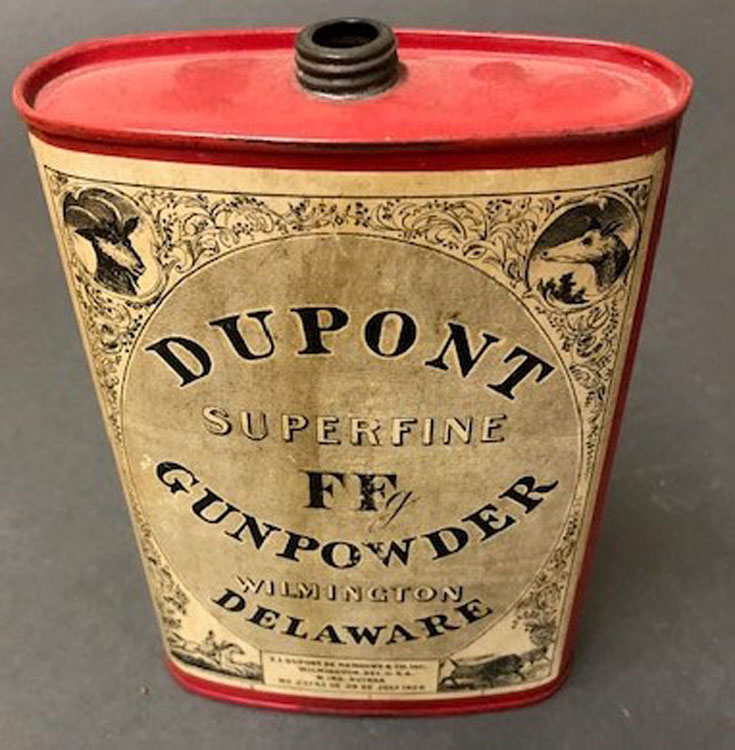

DUPONT gunpowder tin

4 x 6 inches

Gift of Janet Hartford

As described on its decorative label, the empty tin held one pound of superfine gunpowder for the re-loading of bullets for rifles during the 1920s. E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company was founded by Éleuthère Irénée du Pont (1771-1834) in 1802 to manufacture gunpowder. Du Pont, originally from France, was the student of the renowned chemist Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794). The company built factories along the Brandywine River in Wilmington, Delaware and transported materials on the Delaware River. The manufacturing process was dangerous and there were numerous explosions over the years, but blasting in mines and the construction of roads and railroads increased the demand for gunpowder.

Rhodonite box

Material from Russia

4 1/4 x 4 1/4 x 1 1/2 inches

This finely made hinged box of vivid dark pink rhodonite with black manganese oxide minerals is lined with white marble.

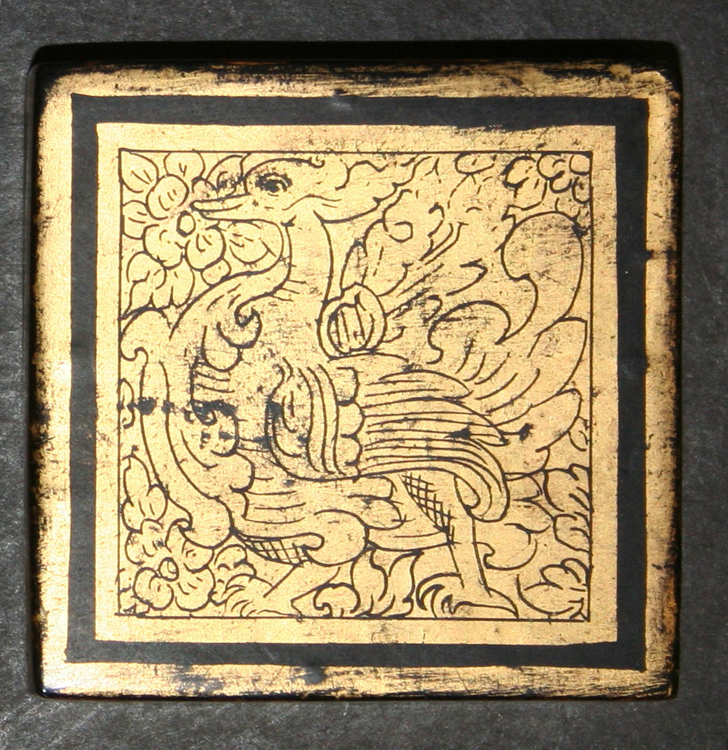

Unknown Artist

Thailand, or possibly Myanmar

Lidded box, ca. 1930 or earlier

Lacquered wood, gold leaf, 4 7/8 inches long x 2 1/4 inches deep

Gift of Dr. & Mrs. Willi Riese

Trinket boxes such as these were, and are, widely used throughout Thailand and Myanmar. This two-part box is like the Japanese inro (similar to the object in the Jewels, Adornments and Keepsakes cabinet ) in that it held medicines, coins, and other small objects. The difference is that boxes such as these would not dangle from a netsuke, but rather, be tucked into a sash, carried in a mesh bag, or slid inside a sleeve.

Unknown Maker

Madagascar

Calabash Cup/Vase, early 20th century

Gourd, brass wire, 1 7/8 inches high

Donor Unknown

This cup was created from a calabash gourd, not to be confused with the large hollow fruits, which grow on trees. Calabash gourds originated in southern Africa and Madagascar and have many uses. In this example, the gourd is enhanced using simple wire decoration, which is both pleasing to the eye and provides a good gripping surface.

Unknown Maker

Moche III, Peru

Seated Priest Effigy Spout Jar, 450-550 CE

Ceramic, Redware, 8 1/2 inches high

Bequest of Miss Jane Maxwell, given in memory of her father, James Maxwell

The utility of this vessel is not fully understood. Moche vessels could have had various everyday uses, as well as serving as funerary objects. This example depicts a warrior-priest in a typical seated position with his hands resting on his lap.

Moche ceramics are normally mold made and are manifested in a narrow range of styles: stirrup spout vessels, bottles, portrait heads, and flaring spout jars. Moche society flourished on the north Peruvian coastal desert between the 1st and the 8th centuries CE, in valleys irrigated by rivers flowing westward from the Andes to the Pacific Ocean.

Unknown Asante Artist

Ghana, Africa

Kuduo, 20th century

Cast Alloy, Copper, Brass

Gift of Geneva R. Steinberger

Kings and persons of influence in the Akan culture own brass vessels called kuduo. These receptacles are meant to hold gold dust (a medium of monetary exchange) or other valuables. The kuduo serves the symbolic purpose of safeguarding their owners' kra, or life force. Kuduo plays an important role in ceremonies intended to maintain the spiritual well-being of those who own them.

Victor Spinski (United States, 1940-2013)

Lidded Vessel, ca. 1968

Porcelain, 40 1/2 inches high

Purchase Award, 7th Regional Art Exhibition, 1968

Victor Spinski is best known for his ceramic trompe l’oeil still lifes of everyday objects such as polystyrene foam coffee cups or plastic spoons in garbage cans. His inspiration came from the Yixing artists of eastern China, as reflected in this monumental, lidded porcelain vessel.

Spinski was Professor of Ceramics at the University of Delaware from 1968-2006. This vessel is an example of his early work done at the university. Despite the traditional appearance, it was made during the period when Spinski was considered a leader in the avant-garde ceramics movement of the 1960s and 1970s. He held a patent on a ceramics photo emulsion process, which allowed him to produce decals. This further enhanced his later trompe l’oeil ceramic designs, such as printed cardboard boxes or portraiture.

Atlas Powder Company

Atlas Blasting Machine, after 1912

8 x 17 x 6 1/2 inches

Gift of Janet Hartford

Blasting machines, invented by Henry Julius Smith of Mountain View, New Jersey, fired a blasting cap to detonate dynamite for use in mining and construction. The machine shown is from the Atlas Powder Company, Wilmington, Delaware and was made sometime after Atlas was split off from the E. I. DuPont Powder Company in 1912. The metal plaque reads:

No. 3-50, Atlas Powder Company, Wilmington, Delaware

Explosives, Capacity, 50-30 feet copper wire, Electric Blasting Caps.