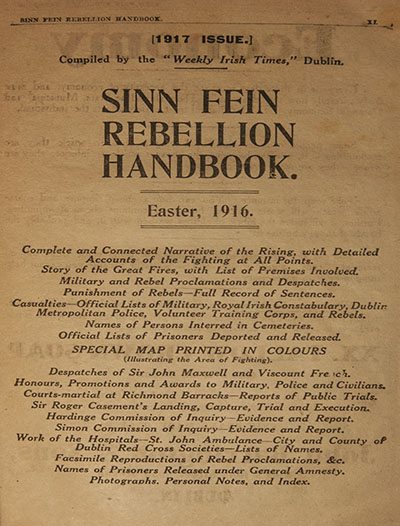

Weekly Irish Times, Dublin, comp. Sinn Féin rebellion handbook. Dublin: Published by the Irish Times, 1917.

The Easter Rising was misunderstood and frequently reported as a Sinn Féin revolt, largely due to Sinn Féin’s reputation as the best known anti-British organization in Dublin at the time. Based on articles printed by the Irish Times in 1916, this 1917 publication remains one of the most comprehensive accounts of the events, documents, and people of Easter Week 1916. It contains the names and personal details of the casualties; names of prisoners; facsimiles of key documents; photographs; a map of Dublin city; a list of the buildings destroyed; full accounts of the court martial hearings and the executions of the fifteen leaders; and the full court details of the trial of Sir Roger Casement.

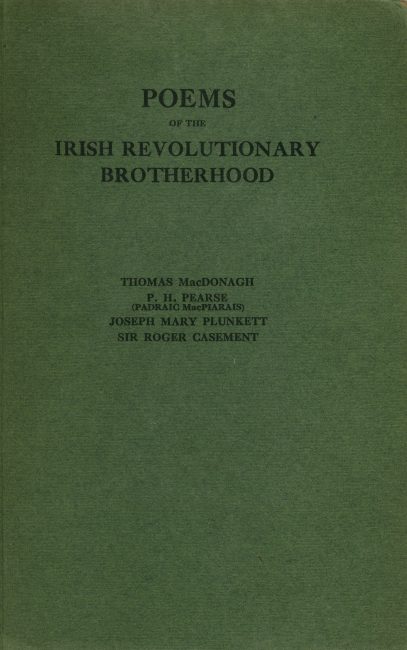

Colum, Padraic, Thomas MacDonagh, Pádraig Pearse, Joseph Mary Plunkett, and Sir Roger Casement. Poems of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1916.

First edition.

Author Padraic Colum (1881-1972) was a proud nationalist, who, like many of his contemporaries, changed his name to the Gaelic after joining the Gaelic League and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Colum published short plays and poetry in Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin publication, the United Irishman. He was a major contributor to the Irish National Theatre.

In his introduction to this volume that collects poetry by the leaders of the Easter Rising, Colum memorializes his friends and praises their poetic efforts and dedication to Ireland: “No attempt need be made to estimate the achievement of the poets of this anthology. An Irishman knows well how those who met their deaths will be regarded – . ‘They shall be remembered for ever; they shall be speaking for ever; the people shall hear them for ever.’ ”

A revised and enlarged edition was released a few months after this first edition, in September 1916.

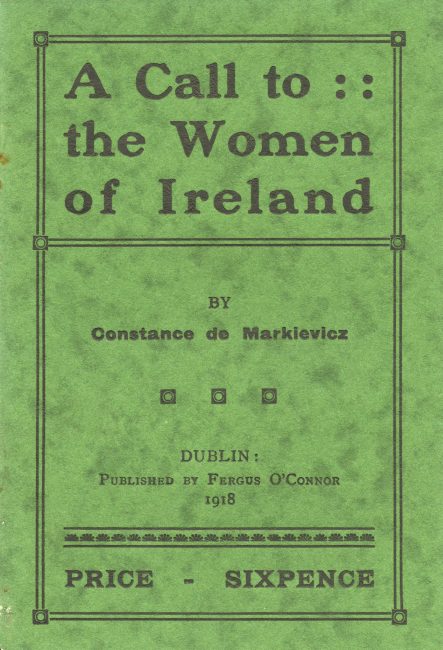

Markievicz, Constance de. A call to the women of Ireland. Dublin: Fergus O’Connor, 1918.

First edition.

Known as the Larkinite rebel countess, Constance Markievicz (1868-1927) captivated audiences who heard her fiery speeches and read reports of her involvement in the Easter Rising. Like Maud Gonne, Constance Gore-Booth came from a wealthy Protestant Ascendancy family. She married a Polish count in 1900, from whom she amicably separated after World War I. The Countess helped to found Na Fianna Éireann and was closely involved with James Larkin and James Connolly in the labor movement and helped striking workers during the 1913 Dublin Lock-Out. An active suffragette like her sister Eva Gore-Booth, Constance Markievicz worked in Maud Gonne’s Inghinidhe na hÉireann.

During the Rising, Constance Markievicz was in second-in-command to Michael Mallin at St. Stephen’s Green and later retreated to the College of Surgeons. She was active during the fighting over the course of the week. She wore the men’s uniform of the Irish Citizen Army. She was originally sentenced to death like the other leaders of the Rising, but her sentence was commuted to life imprisonment due to her sex. She was served fourteen months in Aylesbury Gaol before being released during the General Amnesty of 1917, when many political prisoners were freed.

In 1918, Markievicz was the first woman elected to British Parliament as a Sinn Féin candidate. Frequently avoiding British authorities, she spent much of her time as secretary of the first Dáil on the run. Markievicz vehemently opposed the Treaty of 1921 and set out on a lecture tour of the United States to gain support from the Irish-American community. She joined Fianna Fáil in 1926. Many years of imprisonment and avoiding capture caught up with the Countess, and she died in 1927. Members of the Dublin working class filled the streets to view her funeral procession.

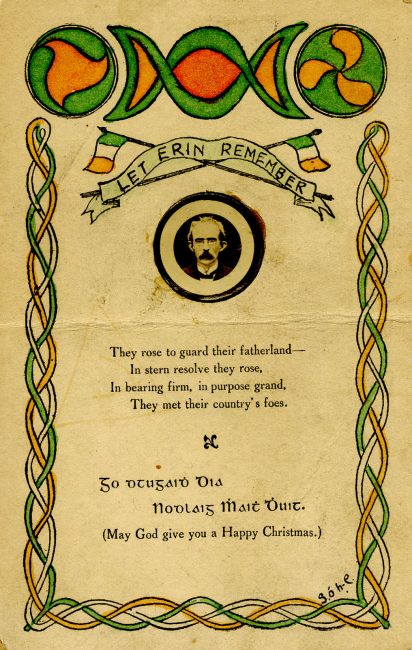

This copy of Brennan’s autobiography detailing his participation in the Rising belonged to his daughter, Maeve Brennan. Laid into this copy was a hand-colored Christmas postcard from Maeve’s godmother, Kathleen Clarke, widow of Rising leader and signatory Tom Clarke. It features a small photograph of Clarke.

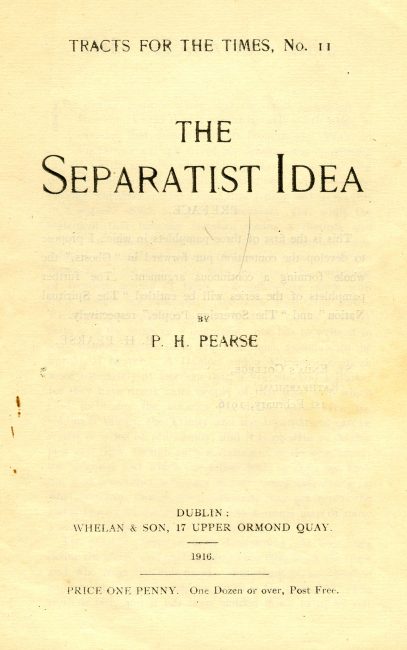

Pádraig Pearse (1879-1916) joined the Gaelic League at age sixteen. Inspired by Christian Brothers at his school in Dublin, he gained an appreciation and deep admiration for Irish language and mythology. From 1903 to 1909, he edited the League’s newspaper, An Claidheamh Soluis (The Sword of Light). In 1908, he founded a bilingual school for boys, St. Edna’s.

Until around 1910, Pearse’s nationalism was cultural and focused on Gaelic language and literature. He became disillusioned with the progress of the language movement and more entranced with the martyrs of the heroic past. He vocally supported Home Rule in 1912, threatening revolution if not passed. He increasingly espoused physical force republicanism and the necessity of blood sacrifice.

Pearse joined the Irish Volunteers at their founding in 1913. His commemoration of Wolfe Tone on the 115th anniversary of his death in 1913 and his graveside oration of Fenian Donova O’Rossa in 1915 caught the attention of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). He was made a member of the IRB Military Council charged with planning the Rising. Pearse was extremely active in carrying out the Military Council’s plans: arranging for German arms; coordinating with James Connolly and the ICA; and routing Eoin MacNeill, head of the Irish Volunteers, whose organization the IRB had infiltrated, to use for the Rising. On April 23, 1916, the Council appointed Pearse Commandant-General of the Army of the Irish Republic and President of the Provisional Government, to be declared the following day.

Pearse served at the rebel headquarters at the General Post Office during Easter Week. Not a soldier, Pearse offered confidence and boosted morale, most effectively through reading the Poblacht na Eireann, the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, on the steps of the GPO on Easter Monday.

Pearse surrendered unconditionally to British forces at 2:30p.m. on April 29 to prevent further death of civilians and his comrades. He was sentenced to death and faced the firing squad on May 3. He was buried next to Thomas MacDonagh and Tom Clarke at Arbour Hill Barracks.

It was through Pearse’s prolific writing that he justified his extreme republicanism. This voice cemented his martyrdom and made him the icon of the Rising.

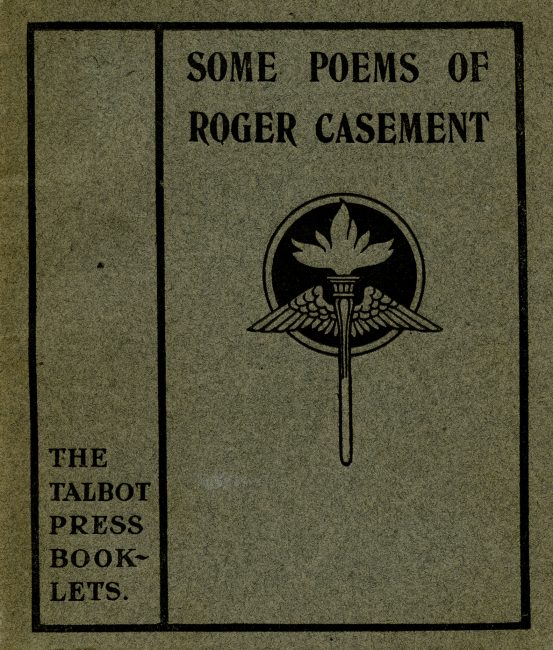

Casement, Roger, Sir. Some poems of Roger Casement. Dublin: The Talbot Press, 1918.

During a successful career as a British diplomat and human rights advocate, Roger Casement (1864-1916) began to be involved in Irish nationalism. Radicalized by the Third Home Rule crisis in 1912-1913, he helped organized the Irish Volunteers. In 1914, he supported Germany as being an obstacle to Great Britain countering Irish Home Rule. Casement traveled to Berlin in hopes of persuading Germany to provide support for the Irish cause. In 1916, he was captured returning to Ireland via German submarine, on his way to persuade the leaders of the Rising not to go forward with their plans without German support.

Although he had no direct part in the Rising, Casement was arrested by the British and charged with treason. The trial began on June 26, after the leaders of the Rising had already been executed and the manner of their executions had been discovered by the public. Casement’s diaries (“The Black Diaries” as they were called) detailing his homosexual affairs were seized from his lodgings, and the British authorities attempted to use them against him in the press. He was found guilty of high treason on June 29 and stripped of his knighthood on June 30. Appeals for reprieve by W.B. Yeats, Arthur Conan Doyle, George Bernard Shaw, Lady Gregory, and others were unsuccessful.

In 1922, Clement Shorter published a pamphlet of George Bernard Shaw's Discarded Defence of Roger Casement. In his introduction to the pamphlet, Shorter wrote that “[the] execution of Casement was the final flash of imbecility in our government of Ireland.” Although George Bernard Shaw did not know Casement personally and did not necessarily agree with his politics or his methods, he believed that Casement should have been treated as a prisoner of war and not a traitor. Shaw offered Casement assistance with his defense, the manuscript of which Casement received and apparently annotated, but did not use. Shaw points out that the annotations on this manuscript differed from the handwriting in the “notorious diaries” being used by the Crown against Casement. The authenticity of the diaries was contested for decades.

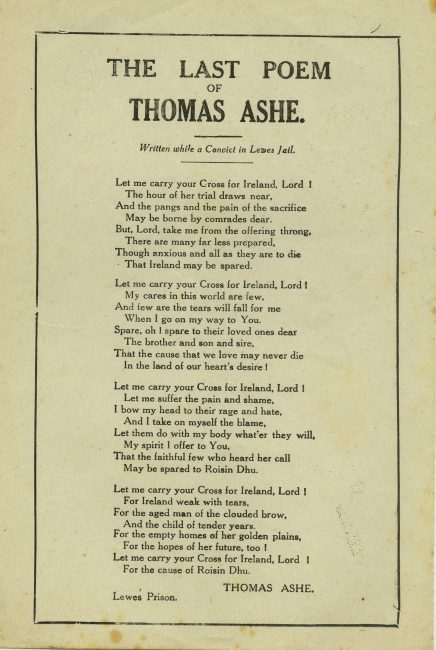

Ashe, Thomas. The last poem of Thomas Ashe written while a convict in Lewes Jail. [Ireland: s.n.,] 1917.

Thomas Ashe (Tomás Aghas, 1885-1917) was a founding member of the Irish Volunteers. Committed to physical force, he was a member of the IRB, though not part of the group that planned the Rising. Ashe led the 5th Battalion of the Dublin Brigade (known as the Fingal Volunteers), and his unit’s guerilla tactics were among the only successful military maneuvers during the Rising. The Battle of Ashbourne took place on April 28 when the Volunteers attempted to raid a Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks north of Ashbourne, Co. Meath. Ashe surrendered upon receiving Pearse’s orders. His original sentence of death was commuted to life imprisonment; after serving time in Kilmainham Gaol, Ashe was interned at Lewes Jail, where he penned his most well-known poem, “Let me carry your cross for Ireland, Lord!” in 1917.

Ashe was arrested two months after his release in June 1917 after a speaking engagement. Sentenced to hard labor at Mountjoy, Ashe was denied basic provisions such as bedding and proper clothing. He went on a hunger strike on September 20 and died on September 25. The inquest after his death found he succumbed to pneumonia brought on by abuse and force-feeding by prison authorities.

Ashe’s funeral was the first following the Rising. Michael Collins gave a graveside oration.