Yeats, William Butler. Easter, 1916. London: Privately printed by Clement Shorter, 1916. One of 25 copies.

Between May and September 1916, William Butler Yeats wrote what would become “Easter, 1916,” a poem that was not the ringing endorsement of republicanism many had hoped it would be (though it was interpreted as such). Despite his prominent role in the Gaelic Revival and establishment of the Abbey Theatre in the earlier part of the century, Yeats became increasingly disillusioned with radicalism. Irish historian and Yeats biographer R.F. Foster notes that “Easter, 1916” instead “emphasized not only the bewildered and delusional state of the rebels, but it move[d] on to a plea for the flashing, changing joy of life rather than the harsh stone of fanatical opinion fixed in the effluvial stream.”

O’Casey, Sean. The Plough and the Stars. London: Macmillan and Co., 1926.

Sean O’Casey is best known today as a playwright, but he was a fierce nationalist, socialist, and champion of Jim Larkin. O’Casey was the first Irish playwright to write about the working and poor classes.

The third in O’Casey’s Dublin Trilogy (which includes Juno and the Paycock and Shadow of a Gunman), The Plough and the Stars was performed in 1926, ten years after the Easter Rising, and was not well received. O’Casey, who was never in favor of an armed uprising and the tradition of blood sacrifice, questioned the fervent nationalist rhetoric of the time and presents the defeat of the rebels as inevitable. Audiences felt O’Casey was demeaning those who had died for Ireland and negatively portrayed Irish people. On the show’s fourth night, the audience rioted—joined by the widows of 1916’s fallen. W.B. Yeats took to the stage in an attempt to quell the crowd, and, recalling his 1907 speech to the audience of The Playboy of the Western World, he said, “You have disgraced yourselves again. Is this to be an ever recurring celebration of the arrival of Irish genius?”

Russell, George William. Salutation: a poem of the Irish rebellion of 1916. London: Privately printed by Clement Shorter, January 1917.

1 of 25 copies.

George Russell William (1867-1935), better known by his pseudonym Æ, was a central figure of the Irish Literary Revival. His mysticism and belief in the ancient spirituality embodied in Ireland drew him to the Literary Revival. With Lady Gregory and W.B. Yeats, Æcontributed to the theoretical foundations of the national literature, as well as poetic and dramatic works he hoped would inspire nationalist pride. He worked with Sir Horace Plunkett on the agricultural co-operativism movement and was deeply invested in Ireland’s economic concerns, especially the 1913 Dublin Lock-Out. Æwas nominated as a member of the 1917-1918 Irish Convention that attempted to address the Irish question.

Æwas an ardent pacifist and was not in favor of the physical force doctrine espoused and practiced by the leaders of the Rising. In his elegy “Salutation,” he expresses ambivalence and admiration for those who fought passionately and died for their dream, even if it was not one he shared:

Their dream has left me numb and cold

And yet my spirit rose in pride

Refashioning in burnished gold

The images of those who died

Or were shut up in penal cell

Here's to you Pearse, your dream, not mine

And yet the thought- for this you fell

Has turned life's water into wine

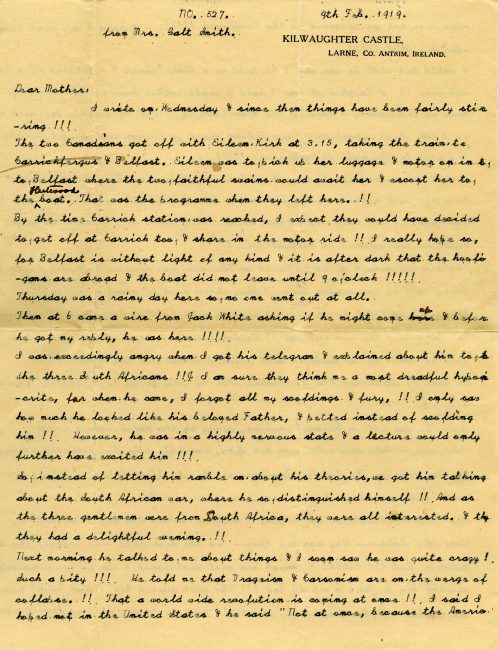

Galt-Smith, Elizabeth Shipley Bringhurst. Typed letter to Anna James Webb Bringhurst, June 12, 1916.

Shipley–Bringhurst–Hargraves family papers

Elizabeth (Bessie) Shipley Bringhurst Galt-Smith (1863-1932) was the daughter of prominent Wilmington businessman Edward Bringhurst, Jr. In Ireland, the Galt-Smiths first lived in "Meadowbank," a house in a suburb north of Belfast. In 1891, John Galt Smith signed a thirty-year lease on Kilwaughter Castle, ancestral home of the Galt family, in Larne, County Antrim. Bessie traveled to Ireland in June of 1914 and became stranded due to the onset of hostilities leading to World War I. She was unable to book safe passage back to America until 1919. After the end of World War I, the deteriorating security situation caused by the escalating War for Independence prompted her to vacate Kilwaughter.

Bessie continues to share news of the Rising as she receives it. The end of this letter shows Bessie as an Ulster Unionist and her views on the Rising after the execution of twelve of its thirteen leaders. Roger Casement’s fate was yet to be determined at the date of writing; he was hanged in August. “Of course the thing agitating us Loyalists of Ulster is the Home Rule Nonsense. Ulster is to be excluded & to remain as part of the Empire. Of course the Nationalists of the south do not want this, because all the money & industry are up here, & they want us to pay their expenses!! I think they will soon grow to hate the greatly increased taxation, because England will scarcely now give money to the rebels to carry on their wickedness!! The saying now is that they will either shoot Sir Roger Casement or make him a Peer!!!!!”

Stephens, James. The insurrection in Dublin. Dublin and London: Maunsel and Co., 1916.

Not to be confused with the legendary Fenian of the same name, novelist and poet James Stephens (1880-1950) was a close friend of Thomas MacDonagh. He published nationalist lyrics in Arthur Griffith’s United Irishman and published a tribute to Griffith in 1922. Not involved in the Rising itself, Griffith recorded what occurred near his home in Dublin: “From the window of my kitchen the flag of the Republic can be seen flying afar. This is the flag that flies over Jacob's Biscuit Factory, and I will know that the Insurrection has ended as soon as I see this flag pulled down.”

Shorter, Dora (Sigerson). Sixteen Dead Men and Other Poems of Easter Week. New York, M. Kennerley, 1919.

Poet and journalist Dora Sigerson Shorter (1866-1918) is said to have died of heartbreak for Ireland. The Sigerson household in Dublin hosted a salon for the cultural and literary leaders of the late nineteenth century, and there, Dora Sigerson met many of the luminaries of the early Gaelic Revival. She married journalist and printer Clement King Shorter (1857-1926) in 1896. Deeply affected by the Easter Rising, the Shorters together mounted an (unsuccessful) defense for Roger Casement. Dora Shorter designed and sculpted a memorial statue that stands in Glasnevin Cemetery. Her volumes of poetry between 1916 and 1918 indicate a growing despair over British control of Ireland.