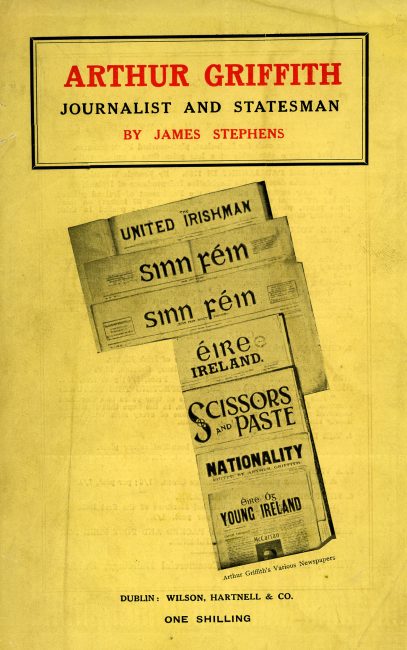

Stephens, James. Arthur Griffith, journalist & statesman. Dublin: Wilson, Hartnell & Co., 1922?

The rise of militant groups in the first decade of the twentieth century such as Sinn Féin, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the Irish Citizen Army, and the Ulster Volunteers occurred for a variety of reasons: disillusionment with failed parliamentary politics and the leaders of the Irish Parliamentary Party after the fall of Parnell; the centenary of the 1798 Rebellion and re-establishing a link with physical force tactics for revolution; the effects of cultural nationalist groups like the Gaelic League and the Gaelic Athletic Association.

The Sinn Fein movement was developed by printer and writer Arthur Griffith (1872-1922). Formerly a Parnellite, Griffith established the Sinn Féin Party in 1905 based on the ideas that Ireland could “establish in [its] capital a national legislature endowed with the moral authority of the Irish nation” that Britain would be forced recognize. Griffith also advocated protective tariffs to support Ireland’s domestic industries. The choice of the name “Sinn Féin” (meaning “we ourselves” or “alone”) alludes to the spirit of political, cultural, and economic independence and self-sufficiency. Griffith himself did not take part in the Easter Rising, but the newspapers had dubbed it the “Sinn Féin Rising,” as it was an openly anti-British propagandistic body centralized in Dublin. After Easter Week, radical and more moderate republicans gathered under the banner of Sinn Féin. It gained influence through Griffith’s writings that boycotted British military conscription of Irish men. In 1917, the party set forth its new agenda to “[secure] the international recognition of Ireland as an independent Irish republic. Having achieved this status, the Irish people may by referendum freely choose their own form of government.” In 1918, the Party swept the parliamentary elections with Eamon de Valera, the only surviving Easter Rising commander, as its leader.

Macnamara, Brinsley. The clanking of chains: a story of Sinn Féin. New York: Brentano’s, 1919.

Brinsley Macnamara is the pseudonym of John Weldon (1890-1963), who is best remembered for his controversial first novel The Valley of the Squinting Windows (1918). In The Clanking of Chains, Macnamara satirizes the romantic nationalism and the pettiness he saw fueling patriotism during the War of Independence. Some critics considered it his worst novel, mainly for the lack of characterization. Macnamara was also a successful playwright, who, along with Sean O’Casey and George Shiels, helped keep the Abbey Theatre financially stable during the difficult years after the Rising.

Figgis, Darrell. Sinn Féin catechism. [S.l.: s.n., 1918?]

This pocket-sized pamphlet presents Sinn Féin’s anti-British values in a question-and-answer form. Darrell Figgis was a prolific writer and published in many genres including poetry and satirical fiction. Through conversation between a father and son, The House of Success (1921) portrays ideological differences between generations from Parnellism to the Easter Rising. Figgis also wrote The Return of the Hero (1923) under the pseudonym Michael Ireland, which, when discovered, shocked the literary establishment for its quality and unusual choice of genre for Figgis.

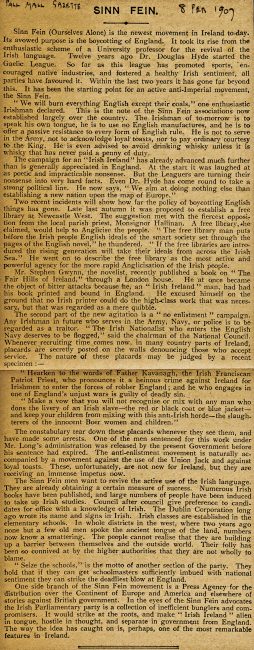

“Sinn Fein.” Pall Mall Gazette, 1907.

The author blames Douglas Hyde, the Gaelic League, and their push to de-Anglicize Ireland for Sinn Féin’s “boycott [of] England,” including refusing to enlist in the British military, speaking Gaelic, and teaching Irish history and culture. Sinn Fein’s success would make Ireland “alien in tongue, hostile in thought, and separate in government from England.” The author also refers to Sinn Féin by the frequently quoted mistranslation, “ourselves alone” (it is more accurate as “alone” or “we ourselves.”) This clipping was originally laid in a copy of the journal Shanachie (the English spelling of seanachaí, pronounced shan-na-key, a traditional Irish storyteller).