The Sinn Féin representatives at the 1921 Treaty negotiations, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, hoped for a sovereign, united Ireland. British Prime Minister Lloyd George insisted that while Ireland must remain under the British Crown, he would attempt to offer as much self-government as possible and to avoid partition. On December 6, 1921, the Treaty was signed after much negotiation. Southern Ireland would be known as the Irish Free State. It would be allowed full control over domestic affairs, including the power to oversee its economy and to raise an army, and it would be given a good deal of freedom over matters of foreign policy. The Irish Free State, however, was not a republic: it would continue to be a part of the British Empire with the Crown as its head of state. Northern Ireland would also be partitioned.

The Treaty deeply divided all nationalists in Ireland. Those in favor of the Treaty (Nationalists) reasoned that it had the support of most Irish citizens and rejecting it would only lead to more war with Britain. Those against the Treaty (Republicans) argued that it failed to achieve precisely what had been fought for since 1916: an Irish republic.

Significant hostilities began in June 1922 when Michael Collins led the Provisional Government’s attack on Anti-Treaty forces in Four Courts in Dublin. Many who had fought together in the IRA during the War of Independence now fought against one another. The Anti-Treaty republicans led a destructive guerilla campaign, which dealt its most serious blow with the assassination of Michael Collins in his hometown of Cork. The government set out to capture and execute the guerilla fighters in the autumn of 1922.

After consistent attacks and reprisals through the end of 1922 and into 1923, anti-Treaty IRA leader Frank Aiken called for a ceasefire; he ordered the remaining fighters in May 1923 to “dump arms” and go home. No end to the war was ever officially called or negotiated.

An election in August 1923 placed the pro-Treaty party, Cumman na nGaedheal, in power. During the war, Ireland’s citizens suffered from a general lack of government and effective policing for all. Although the Partition was established at the beginning of the war, the bitter violence in the Free State only served to undermine the republicans’ goal of unification, generating hostilities for decades that would play a large role in the Troubles. The anti-Treaty republicans reformed as the Fianna Fail in 1927 and came into power in 1932. Two of Ireland’s contemporary political parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, are direct descendants of the pro- and anti-Treaty sides, respectively.

Ní Shuibhne, Máire. The Republic of Ireland. [S.l.: s.n], 1933.

Mary MacSwiney (1872-1942) was the sister of Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Cork Terence MacSwiney, who died after a legendary hunger strike. She became leader of Sinn Fein in 1927 when Eamon de Valera resigned. Mary MacSwiney was a member of the Gaelic League and Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland). She was strongly anti-Treaty during the Civil War.

Stuart, Francis. Lecture on nationality and culture. Baile Átha Clíath: Sinn Féin Ardchomhairle, 1924.

Poet and novelist Francis Stuart (1902-2000) was imprisoned in 1922 during the Civil War, when he ran messages for de Valera and edited anti-Treaty pamphlets. His first volume of poetry, We Have Kept the Faith (1924), earned him some credibility among the republicans, but not among the literary elite, including W.B. Yeats. Stuart married Iseult Gonne, daughter of Maud Gonne, in 1919, after converting to Roman Catholicism.

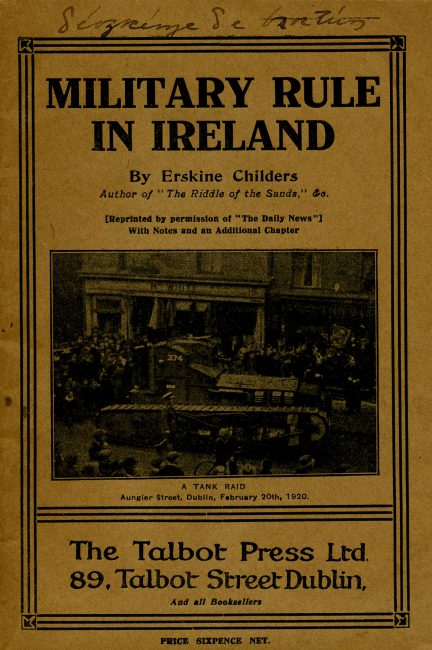

Childers, Erskine. Military rule in Ireland. Dublin: Talbot Press, 1920.

English-born Erskine Childers (1870-1922) devoted himself to Irish Home Rule prior to World War I. He used his own yacht during the Howth gun-running incident of 1914 to provide German arms to the Irish Volunteers. He did serve for Great Britain during World War I, but by the end of the war, he fully supported an Irish republic. In 1921, he was elected a member of the Dáil Éireann and became the Dáil’s minister of propaganda. Childers attended the delegation that negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and opposed Collins and Griffith’s concessions. Ardently anti-Treaty, Childers used his writing talents to support the IRA. He was arrested during the Civil War and executed before a firing squad.