The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) planned the Easter Rising on the traditional republican principle that “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.”

To fight its international wars, England had need of Irish soldiers, and many fought and died in service for Great Britain. Prime Minister H.H. Asquith introduced the Third Home Rule Bill into Westminster in 1912, but the onset of World War I postponed solving “the Irish question.” The Home Rule Bill did become law on September 28, 1914, but its practice was suspended until after the war. Both unionist and nationalist leaders initially supported the British war effort, but more militant republicans opposed Irish enlistment; England’s claim to “make small nations free” was considered quite ironic.

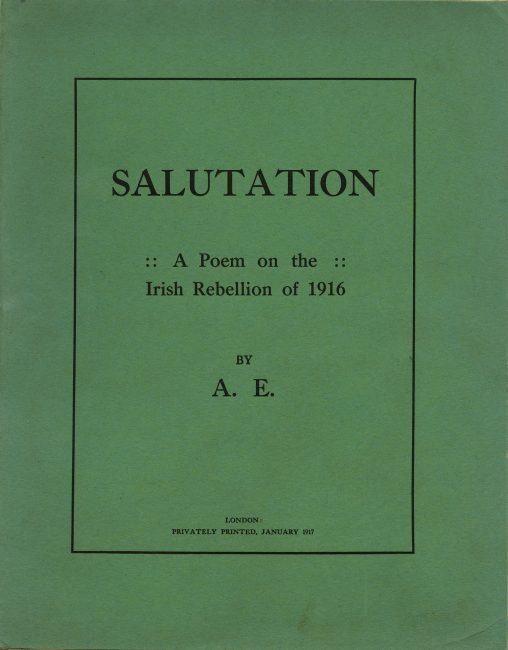

Planning for an insurrection in Dublin began in 1915. The small Military Council of the IRB—comprised of Thomas Clarke, Sean MacDermott, Padraig Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt, Joseph Mary Plunkett, James Connolly, and Thomas MacDonagh—collaborated with James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army and the Irish-American Clan na Gael and infiltrated Eoin MacNeill’s Irish Volunteers. The IRB also hoped to make connections with Germany, with whom they felt Ireland had no conflict, and take advantage its enemy status with Britain.

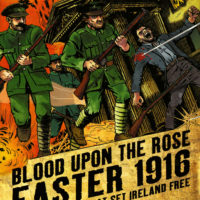

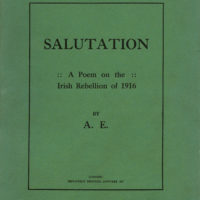

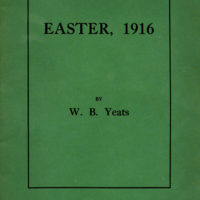

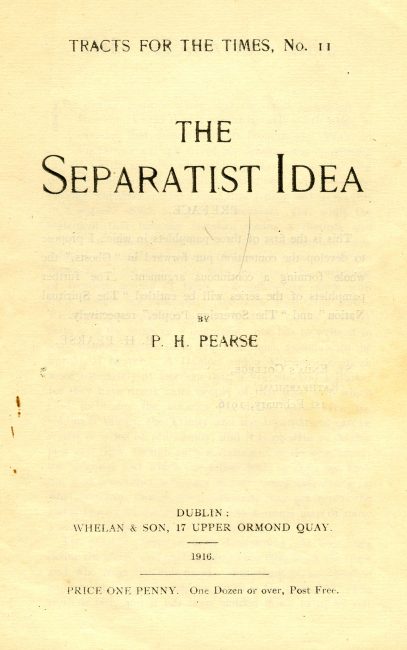

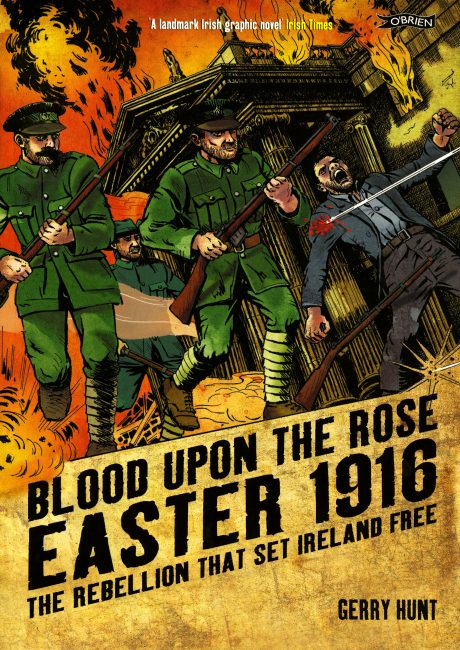

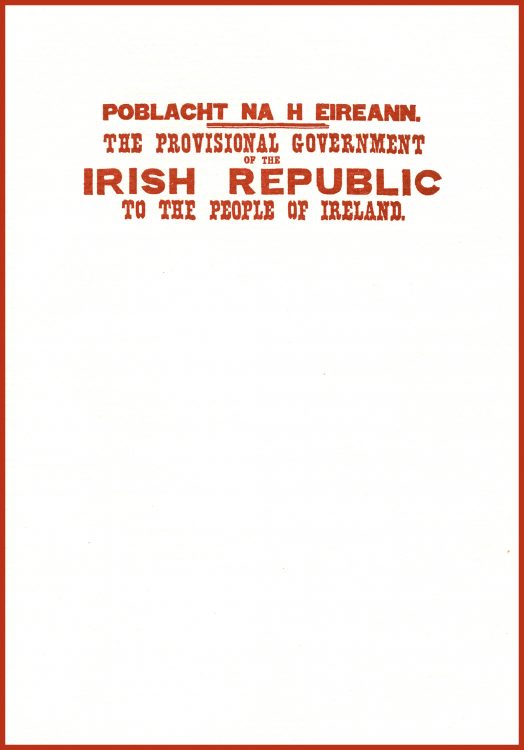

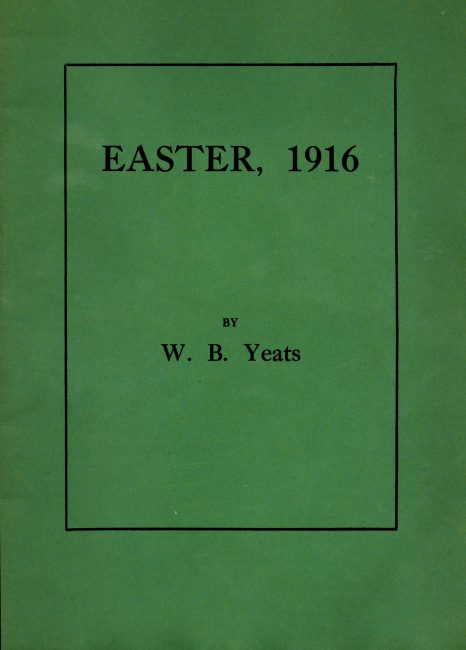

The small Military Council of the IRB declared itself the Provisional Government and signed the Poblacht na Eireann, the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Shortly after noon on April 24, 1916, Pádraig Pearse emerged from the newly formed headquarters of the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic at Dublin’s General Post Office. He read—to a very small crowd—the hastily printed Proclamation of the Republic (Forógra na Poblachta), which not only asserted Ireland’s right to independence, but also justified the cause for armed rebellion, bloodshed, and sacrifice within the tradition of the Irish physical force movement.

The Rising came as a surprise to Great Britain, as well as to most of Ireland’s citizens. The rebels seized prominent locations across Dublin.

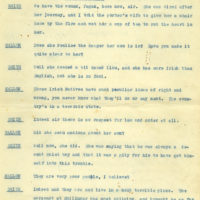

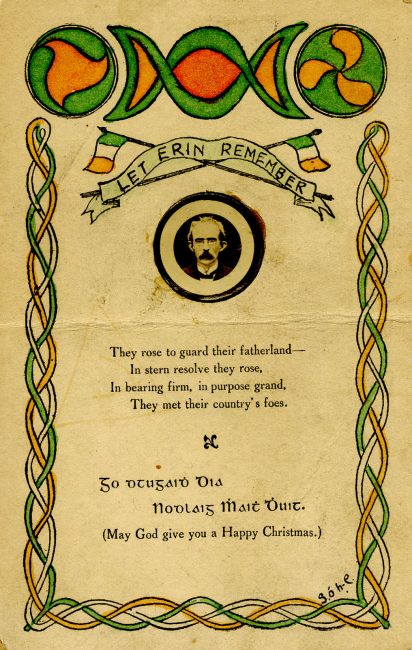

Reaction during and immediately after the Uprising was mixed. It had been disruptive and, to many, needlessly violent: by the end of the week, 64 insurgents, 132 soldiers and police, and about 230 civilians had perished. Over 1,000 people were wounded. The General Post Office, Dublin City Hall, and other landmarks around Dublin were in shambles. But public opinion at home and abroad soon turned with the disclosure of the severity of the executions, the secret trials, and deportations.

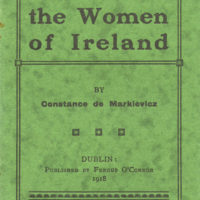

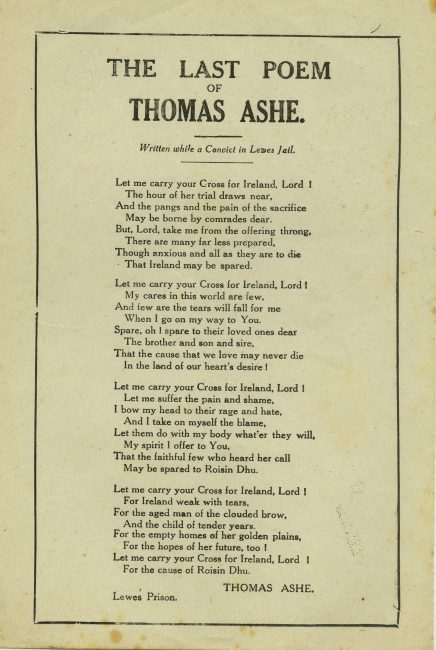

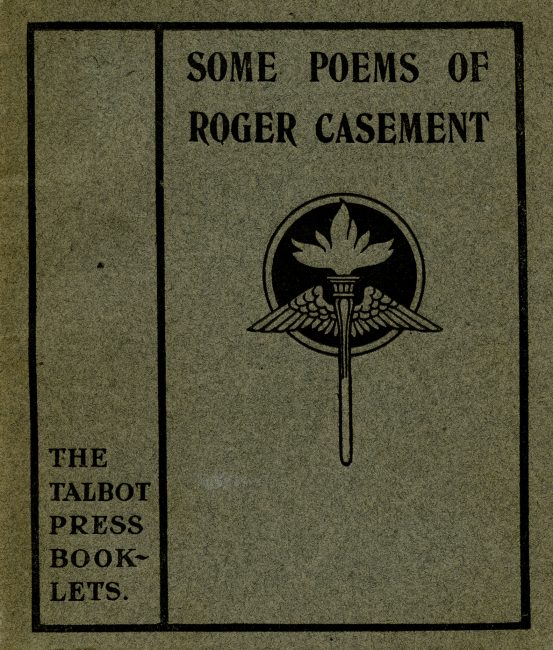

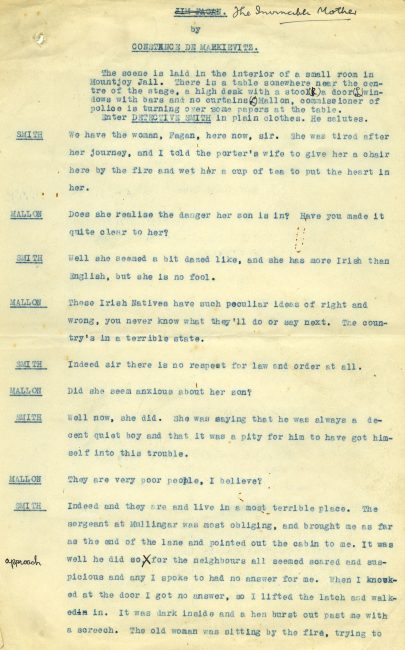

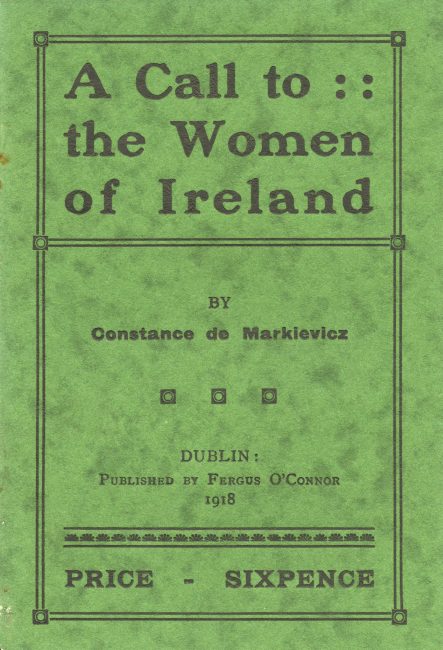

Sixteen men were tried for treason and executed for their part in the 1916 Rising: Thomas Clarke, Eamonn Ceant, Sean MacDiarmada, Padraig Pearse, (his brother) William Pearse, Edward Daly, Michael O'Hanrahan, Sean Heuston, Joseph Mary Plunkett, James Connolly, Thomas Kent, Con Colbert, Thomas MacDonagh, Maj. John Macbride, Michael Mallin, and Roger Casement. Eamon de Valera's death sentence was commuted due to his American citizenship. Constance Markievicz's was commuted for her sex. The leaders of the Rising became cult heroes in the months after their executions.