Gaelic Ireland, called a place of saints and scholars, was split among several kingdoms and united by a High King. Its history is a mixture of legend and fact. Ireland was Christianized from around the fifth century, led by Saint Patrick. Saint Patrick is said to have used the shamrock with its three leaves to explain the doctrine of the Holy Trinity to the Irish.

The Normans invaded Ireland in the twelfth century, and the English claimed sovereignty over Ireland, although they did not rule the entire island until the 17th century colonization by English Protestants. By 1690, William of Orange completed the confiscation of land from the Irish that had begun by the Normans and previous English rulers, including Elizabeth I and Oliver Cromwell. Ireland was viewed as a politically unstable and violent place. Irish trade was crippled by constant invasions and only partial conquest.

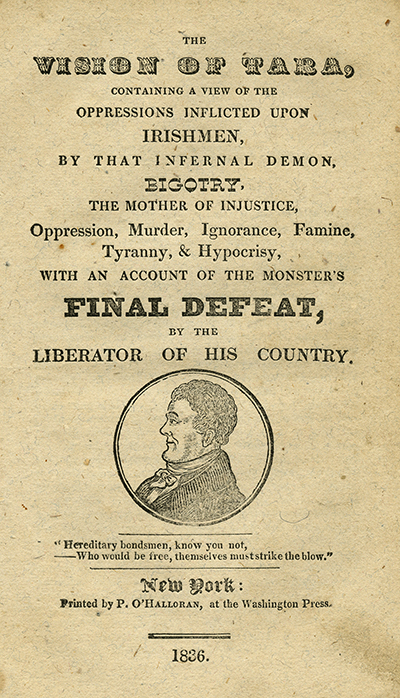

The eighteenth century saw the empowerment of the wealthy landowning English Protestants—known as the Protestant Ascendancy—who disenfranchised the Irish Catholics, denying them education, property or advancement in government. Legislative independence began to take root as early as the 1780s; some of its vocal supporters were of the Protestant Ascendancy who wanted Ireland to be seen as Britain’s equal. Revolutions in America and France inspired Irish rebellions in 1798 and 1803. The 1798 Rebellion was violently suppressed by the British, and gave Britain the opportunity to squash the idea of Irish Home Rule. The 1801 Acts of Union incorporated Ireland into Great Britain. Daniel O’Connell, known as the Liberator, campaigned for Catholic Emancipation and the repeal of the Acts of Union through constitutional reform and peaceful protest.

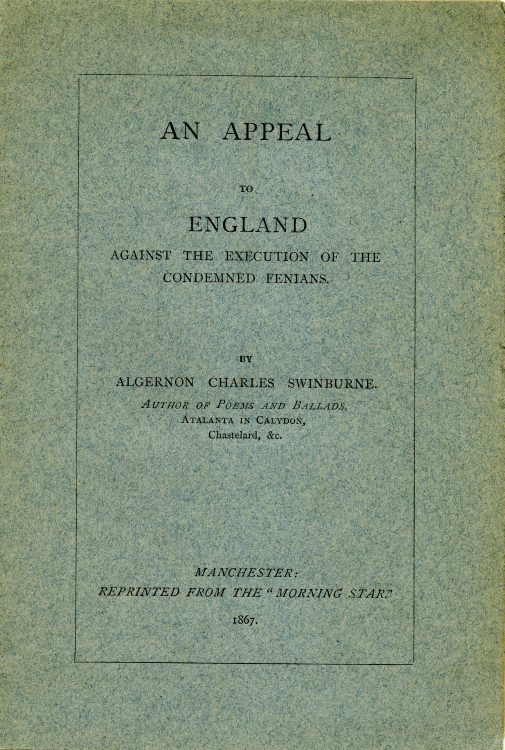

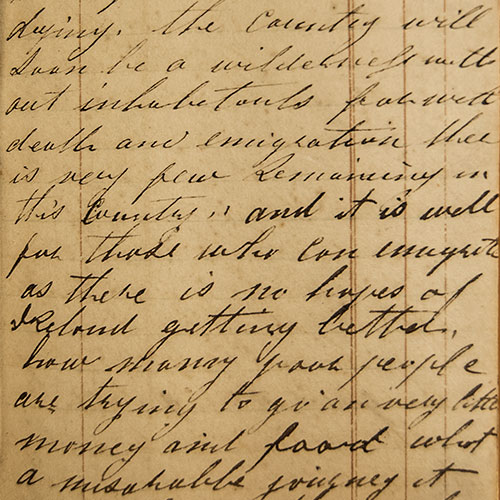

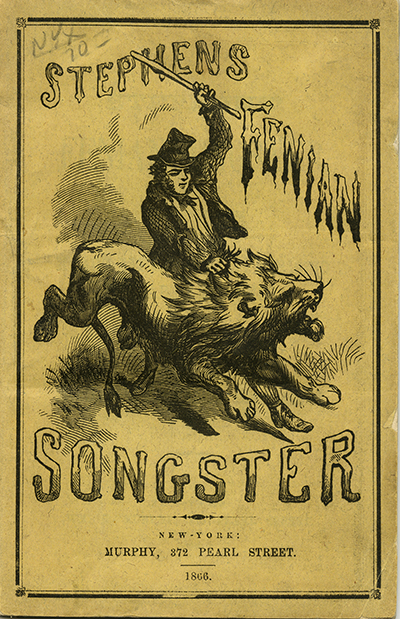

Ireland suffered the Great Famine (an Gorta Mór) during 1845-1851, when the peasantry’s staple crop, the potato, failed. Ireland lost over a million people to starvation and disease and an additional million to emigration. Many went to the United States. Fenianism (whose name refers to the Fianna, legendary warriors in Irish and Scottish myth) emerged in the 1850s. Fenian rebellions during the nineteenth century cemented revolutionary continuity with the use of force from 1798 and 1803. Fenianism had many strands and organizations, including the secret society of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Unionist culture was beginning to appear at the same time. Ulster Unionists in the northern counties resisted the introduction of a Home Rule Bill in the 1880s. The famous line “Ulster will fight, and Ulster will be right!” was coined in 1886 and drew a line in the sand that lasted well into the twentieth century.

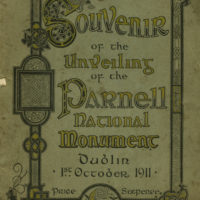

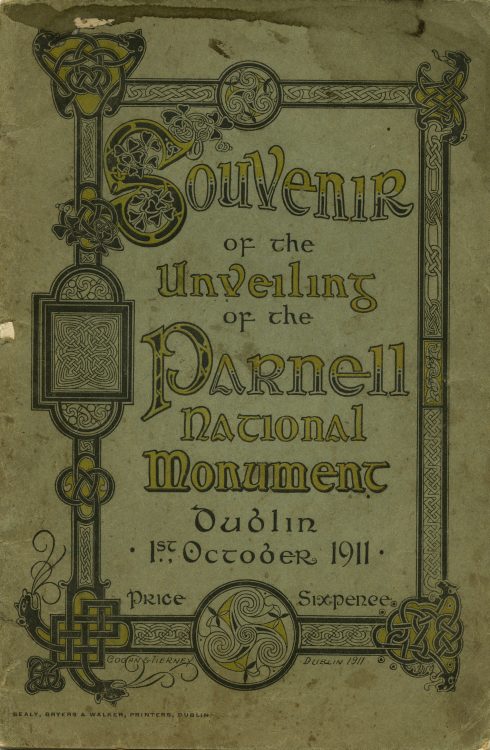

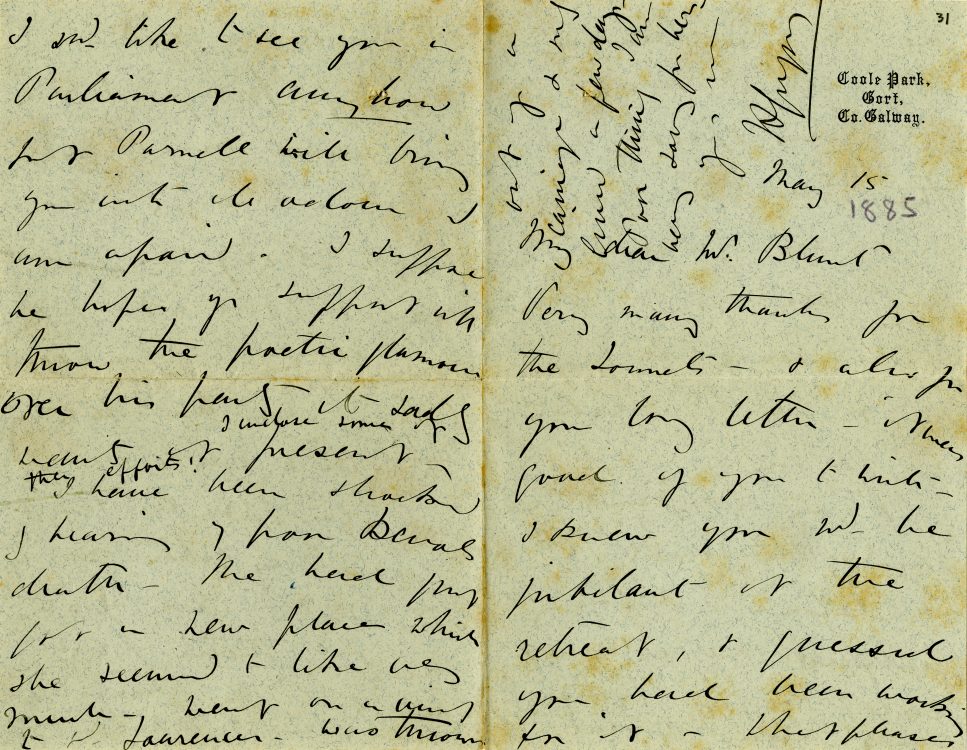

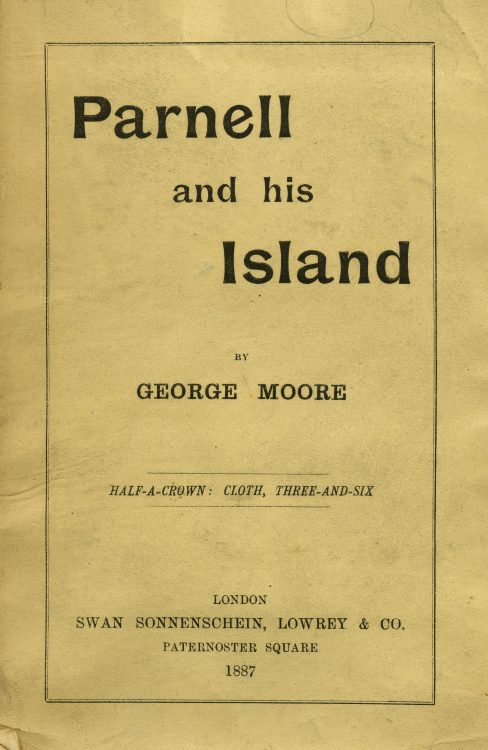

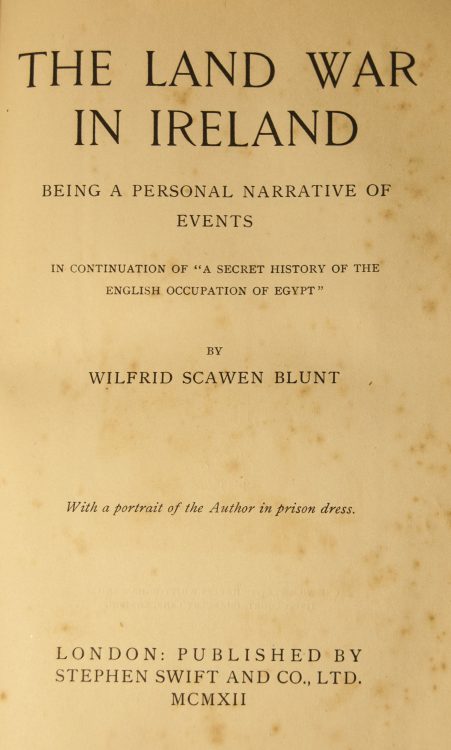

The Irish National Land League, founded in 1879, brought together many land nationalism groups across Ireland. The Irish peasantry had been subjected to evictions, absentee landlordism, and excessive rents on overly subdivided land well before the Great Famine. But it was the evictions of starving families--and the destruction of cottages so tenants could not return--during the Great Famine that prompted more focused action. The Land War (Cogadh na Talún)—not an actual war, but periods of civil unrest and violence caused by the League’s agitation against landlords—occurred between the 1870s and 1890s. Known as the “uncrowned king of Ireland,” Protestant landlord Charles Stewart Parnell formed the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1882, whose legislative agenda was Irish Home Rule and land reform. Parnell’s very public divorce scandal tore the IPP apart, and Parnell was replaced as its leader. Parnell died in 1891, and with him, many thought, the belief that Home Rule could be achieved through parliamentary means.