Ó Doibhilín, Mícháel. Anne Devlin: freedom’s champion. Bethesda, Maryland: Wild Apple Press, 2008.

Anne Devlin (1780-1851) was the housekeeper and confidante of Robert Emmet, a member of the United Irishmen who planned and executed the failed 1803 Rebellion. She was related to Michael Dwyer and Arthur Devlin, who were leaders of the 1798 Rebellion. Anne carried messages all around Dublin for Emmet, who was arrested and hanged (and beheaded) for treason after a short time in hiding. Emmet’s Speech from the Dock was widely quoted by republicans: “When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth, then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written.” Anne Devlin was arrested and interrogated, bribed, and tortured at Dublin Castle and Kilmainham Gaol for several years until she was finally released in 1806. Her unwillingness to inform on Emmet and his associates for the next forty-five years until her death in 1851 made her a legend among Irish revolutionaries.

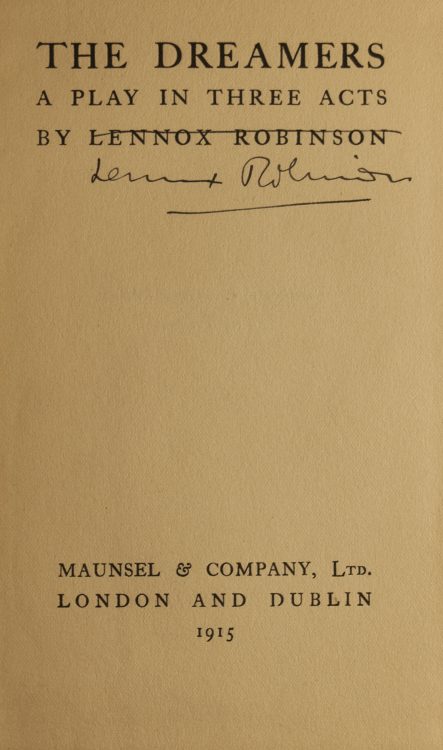

Robinson, Lennox. The dreamers: a play in three acts. London & Dublin: Maunsel & Company, 1915. Author’s autographed copy.

Playwright and theatre director Lennox Robinson (1886-1958) is most noted for his devotion to the Abbey Theatre, which he managed financially and creatively during some of its most difficult times. The Dreamers is one of Robinson’s nationalist works, in which he focuses on Robert Emmet’s role in the failed 1803 Rebellion. In the forward, Robinson defends his choice of title, as many saw Emmet as very practical: “Dreams are the only permanent things in life, the only heritage that can be hoarded or spent and yet handed down intact from generation to generation. Robert Emmet’s dream came down to him through--how many?--generations. He passed it on undimmed. It is being dreamed to-day, as vivid as ever and--they say--as unpractical.” Robinson dedicated the play to his mentor, W.B. Yeats.

Swinburne, Algernon Charles. An appeal to England against the execution of the condemned Fenians. Manchester, England: 1867.

A group of Fenians ambushed the police transport of two IRB members en route to Belle Vue Gaol, killing an officer. The dubious trial proceedings, botched hanging of Michael Larkin, and the prisoners’ inspirational dock speeches led the three to be known as the Manchester Martyrs. Inspired by Edward O’Meagher Condon’s speech at the execution of his fellow Fenians, nationalist T.D. Sullivan wrote “God Save Ireland,” the unofficial Irish national anthem until 1926.

This pamphlet is believed to be a creation of legendary forger Thomas James Wise. Such high-end printing and production for a piece of propaganda in the short timeframe between Swinburne writing the poem (November 20), its publication in The Morning Star (November 22), and the execution of the IRB members (November 23) have raised eyebrows about its authenticity.

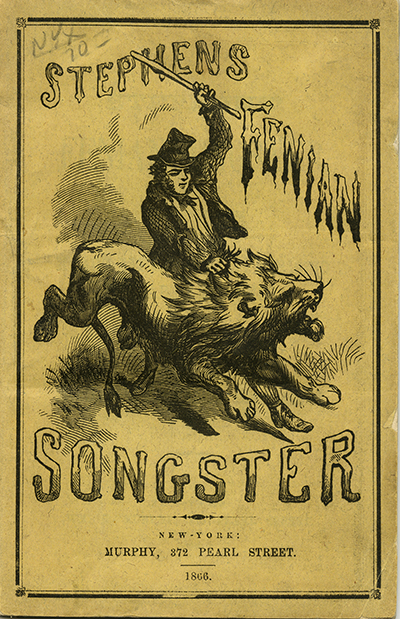

Stephens, James. Stephens’ Fenian songster, containing all the heart-stirring and patriotic ballads and songs, as sung at the meetings of the Fenian brotherhood. New York: W.H. Murphy, 1866.

In 1858, James Stephens (1825-1901) founded the nationalist secret society that would later be known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Stephens had played an active part in the unsuccessful 1848 Young Irelander Rebellion, after which he fled to Paris. In 1859, the American branch of the IRB (the Fenian Brotherhood) was organized under the direction of Gaelic scholar John O’Mahony (1816-1877). In the spring of 1864, Stephens toured the United States, garnering support and funds for the IRB, and promising a rebellion in Ireland by 1865. His plans were discovered by the government, and he was arrested in 1866. He escaped and fled to the United States. The Fenian Rising of 1867 resulted in a series of disorganized skirmishes rather than the guerilla warfare and siege of Dublin the leaders had planned. The IRB however proclaimed a Provisional Government and an Irish Republic, nearly fifty years before the Easter 1916 Rising. Heavily influenced by Karl Marx and socialism, the 1867 Proclamation demands separation of church and state and social equality for workers, tenets not included in the 1916 Proclamation.

Maxwell, W.H. History of the Irish rebellion in 1798: with memoirs of the union, and Emmett's insurrection in 1803. With illustrations by George Cruikshank. London, Baily Brothers, 1845.

Inspired by both the American (1776) and French (1789) Revolutions, Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763-1798), Thomas Russell (1767-1803), Henry Joy McCracken (1767-1798), and William Drennan (1754-1820) formed the Society of United Irishmen in 1791. The group initially intended to unite Catholics, Protestants, and Dissenters (i.e., Protestant Dissenters, such as Presbyterians) to parliamentary reform, but it later sought Irish independence. The United Irishmen were driven underground after open support for France, and Tone’s dealings with France were discovered in 1794. Dublin Castle cracked down on the Irishmen, arresting and imprisoning many of its members, and imposed martial law on most of the country from 1797 to 1798. Fighting broke out in the counties surrounding Dublin: in Down, Wicklow, and Antrim. The rebels had been routed by the British army in Dublin, however, and the city itself was not taken. The Wexford Rebellion was the rebels’ most destructive yet successful campaign, although losses at the Battle of New Ross, the Battle of Arklow, and the Battle of Bunclody drove them back to their camp at Vinegar Hill, where the Rebellion was effectively put down in June-July 1798.

Wolfe Tone is perhaps the best known of the 1798 rebels, regarded as the father of Irish revolutionary republicanism and respected by all nationalists. Pilgrimages to his gravesite in County Kildare are still made. Tone was captured with the French ship Hoche in October 1798. Found guilty of treason, Tone requested the death of a soldier (by firing squad) but was sentenced to be hanged. Tone slit his throat rather than face a traitor’s death. He was patched up instead of being allowed to die by his own hand and warned not to speak, lest he reopen the wound. His last words were reportedly, “So be it.”

This volume was illustrated by English caricaturist George Cruikshank (1792-1878). His illustrations (and others’ in subsequent years) in the satirical magazine Punch typically depicted the Irish as subhuman and apelike. Cruickshank depicted the Irish in the 1798 Rebellion in this volume as gleefully slaughtering the British soldiers.