Martial law continued in Ireland after the Rising until November 1916. Deportations and arrests were common. The executions of the sixteen Rising leaders fueled public hostility against the British and encouraged support of an independent republic. The policies of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) became less and less attractive in these extreme times, and resentment of the IPP’s failure to have achieved Home Rule during World War I further weakened its influence.

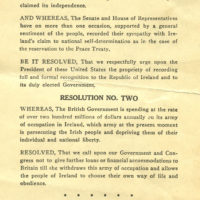

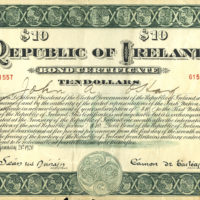

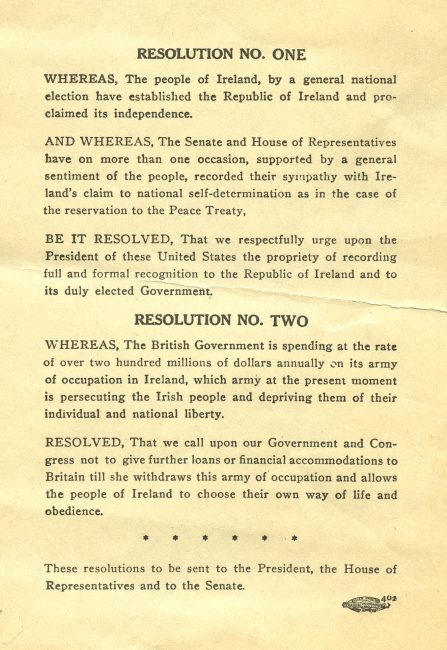

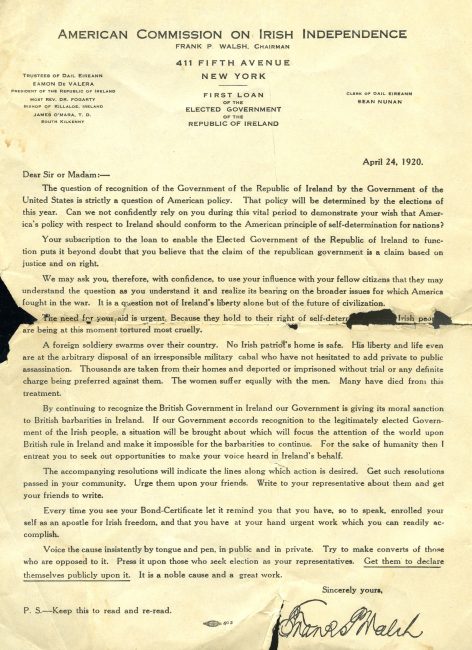

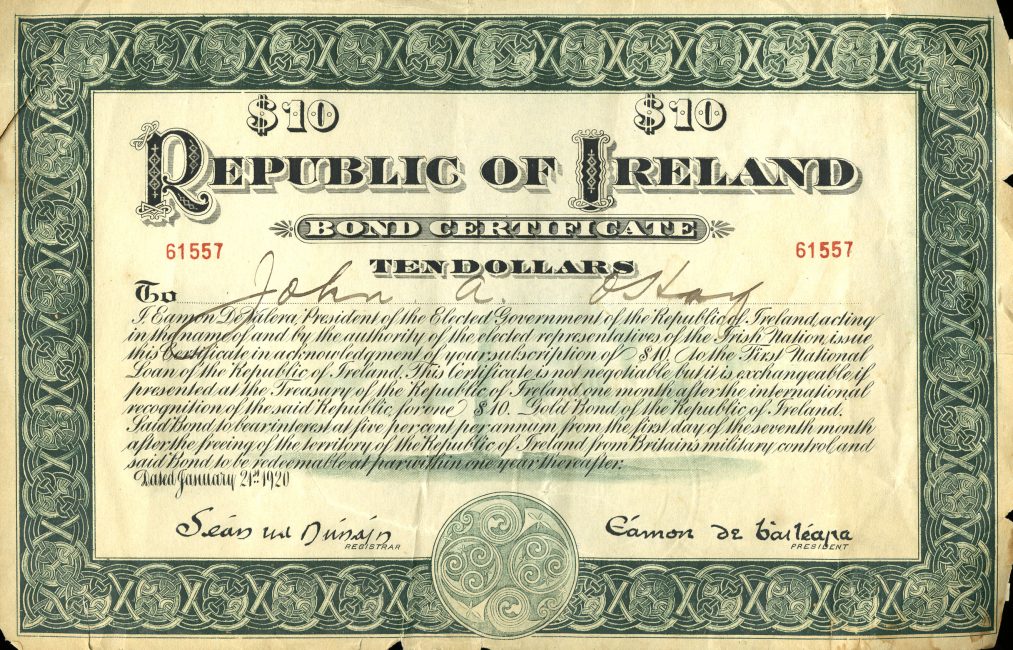

Sinn Féin replaced the IPP as the dominant political party in December 1918. Its leaders declared a republic and established a government in Dublin. The first session of the Dáil met on January 21, 1919, during which the assembled members of Sinn Féin ratified the provisional Irish constitution and proclaimed the Irish Republic. The other statements ratified by the assembly included an appeal for recognition and support by free nations of the world and the resolution that the Republic would be governed by principles of liberty, equality, and justice. The nation’s citizens, especially its children, would be provided for and have access to an “adequate share” of its wealth. James Connolly’s influence can be felt in these words advocating for social justice and dispersal of wealth and resources.

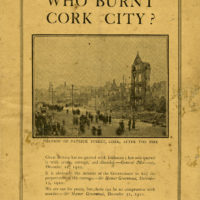

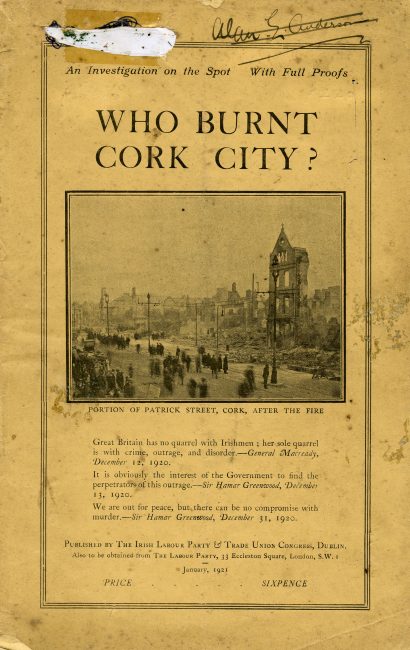

A small number of Irish Volunteers established the Irish Republican Army (Óglaigh na hÉireann) in 1919. Convinced independence could only be gained by force, the IRA—with its limited men, resources, and training—waged a guerilla war against the British. The Sinn Féin government backed the IRA’s activities against the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)—the main British police force in Ireland. The Black and Tans (officially the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve) were recruited to assist the RIC. They were referred to as Black and Tans because of the color of their uniforms. Revolutionary leader Michael Collins (1890-1922) played an important role in supporting and procuring arms for the IRA, acquired intelligence, and identified targets.

On November 21, 1920, Collins’s squad shot and killed nineteen suspected British Army intelligence officers posing as civilians in Dublin. After fourteen agents had been killed throughout the day, members of the Auxiliary Division and the RIC opened fire at a football match at Croke Park, killing fourteen Irish civilians. Three IRA suspects were beaten to death at Dublin Castle, bringing the total number of dead to thirty-one. This success for the IRA became known as “Bloody Sunday,” one of several in Irish history.

A truce was established in 1921, and the Treaty of 1921 was to be negotiated between Sinn Féin and England. Eamon de Valera appointed Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins to attend the negotiations. The Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland (known as the Anglo-Irish Treaty, An Conradh Angla-Éireannach) offered the Irish Free State as a self-governing dominion within the British Commonwealth of Nations (the first use of this term, instead of “British Empire”) and the partition of Northern Ireland.

De Valera opposed the treaty, as it partitioned Ireland and did not create an independent republic. He resigned as president after the Dáil ratified the Treaty, and he led the Anti-Treaty side against Collins and Griffith in the Civil War that followed (1922-1923).