The Museums Collections contain more than three hundred etchings, with examples from the sixteenth century to today. The origins of etching can be traced to southern Germany around 1500, when printmakers adapted the technique from a method of decorating armor. Artists were attracted to the ease of creating an etching, which was essentially a drawing on a metal plate, and the variety of aesthetic effects that the process could achieve. The invention of etching also offered artists a new way to circulate their work without acquiring the specialized skills of an engraver. As etching gained popularity and spread throughout Europe, artists experimented with materials and tools to push the boundaries of the medium.

Jacques Callot, a printmaker from Nancy (now part of France), expanded the expressive capacity of etching in the early seventeenth century with his innovative methods. Callot developed a new etching needle that allowed artists to create different types of lines and devised a process of using multiple acid baths to achieve subtle gradations of light. With this variety of techniques, Callot produced an intricate etched depiction of St. Amond preaching to a crowd of followers in a wooded landscape.

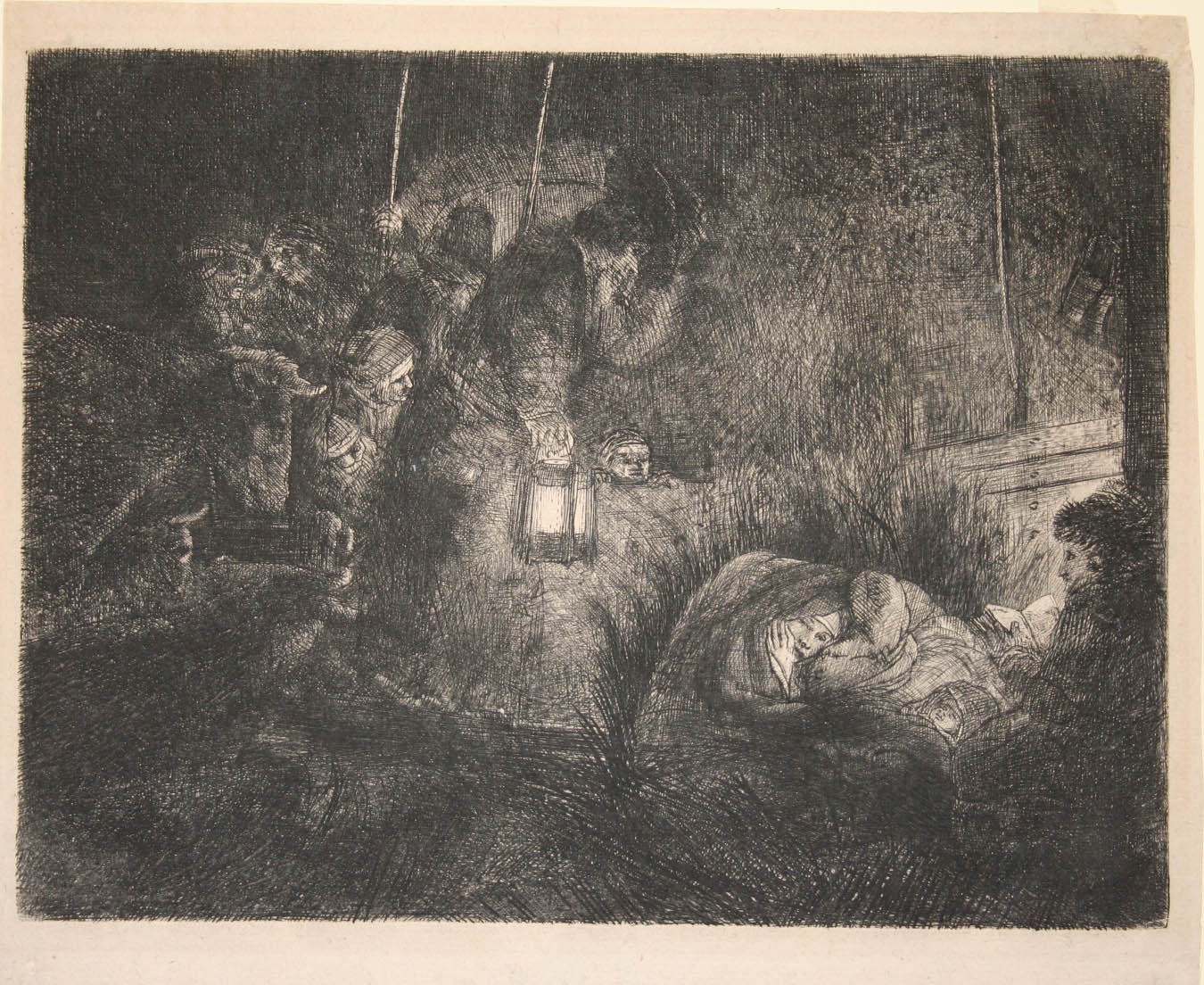

The Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn’s experimental and imaginative use of etching was widely celebrated in his lifetime and greatly influenced future generations of printmakers. Rembrandt was fascinated by the challenge of capturing light and shadow in his prints and continuously innovated methods of representing dramatic tonal effects. In Adoration of the Shepherds, he skillfully combined etching and drypoint to produce the soft, velvety blacks of the crowded nocturnal scene illuminated by an oil lamp.

In the eighteenth century, Giovanni Battista Piranesi employed etching to convey the experience of visiting Rome in his remarkable series Vedute di Roma. Piranesi had a profound admiration for the city of Rome, especially its ancient ruins and modern buildings. He documented these structures with intricate detail while also exaggerating aspects of scale to add grandeur. The large prints were popular as souvenirs for tourists as well as print collectors across Europe, who could use them to imagine their own visit to Rome.

The virtuosic technique of Francisco de Goya is on display in this print from La tauromaquia, a series of thirty-three etchings depicting the history of bullfighting in Spain. Although it was viewed as a celebration of the national pastime, this series also revealed the inherent brutality of the sport, which was controversial even during Goya’s lifetime. Goya used a variety of etched marks and subtle areas of aquatint tone to illustrate this dramatic moment in the bullring.