In the mid-nineteenth century, etching as an original art form experienced a revival in France and England. The technique had waned in popularity early in the century, when it began to be used primarily to copy paintings rather than to make original works of art. In the 1860s, however, artists attempted to reclaim the medium from its associations with mass production and industry. With its close relationship to the practice of drawing, etching was promoted by those reviving the medium as more authentic and expressive than other forms of printmaking. The artists of the etching revival celebrated the work of past innovators such as Rembrandt and emphasized the creative capacity of their prints.

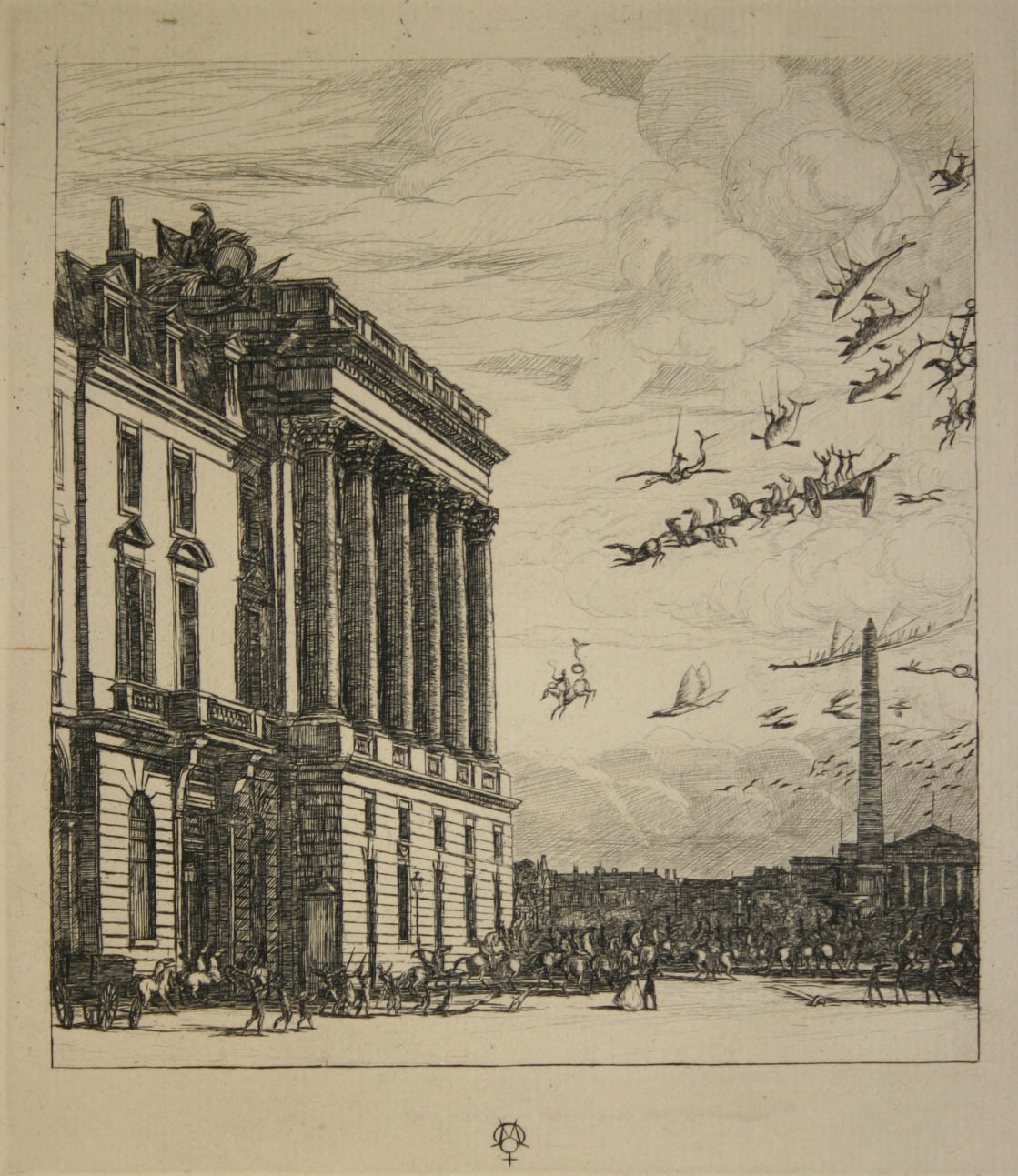

One of the leading artists in the effort to revive etching was the French printmaker Charles Meryon. His views of the rapidly modernizing city of Paris were admired by artists and collectors for their technical skill and abundance of detail. In prints such as Le Ministère de la Marine, the precise depiction of urban architecture is offset by the addition of fantastic elements. Meryon suffered from prolonged mental illness and often inserted his hallucinatory visions into his etchings. Here a procession including a horse-drawn chariot, boats, whales, serpents, and cowboys descend from the sky toward the French Admiralty building.

In England, Francis Seymour Haden was among a group of artists who helped spur the revitalization of the etching technique. Trained as a surgeon, Haden began making prints in his leisure time but ultimately produced more than two hundred plates. He described the etched line as “free, expressive, full of vivacity” in comparison to the “cold, constrained, uninteresting” marks made by the engraving burin. In this depiction of a landing area for the ferry along the Thames, Haden used a combination of hatched marks and gestural lines to add a sense of dynamism to a serene view of the river.