Arthur Conan Doyle, 1859–1930

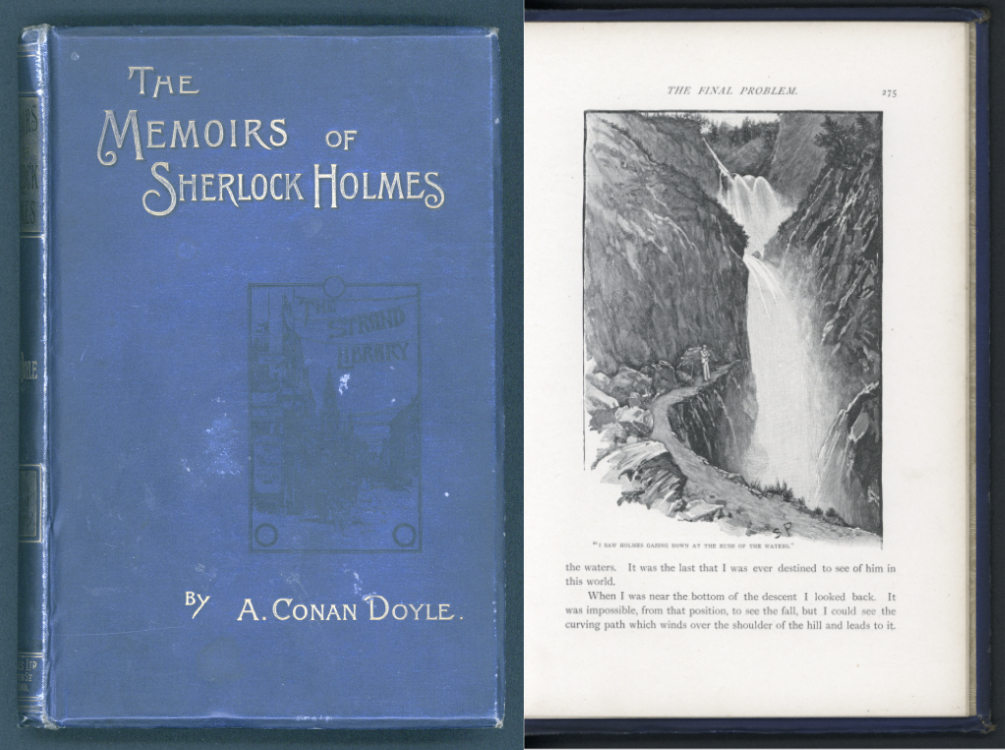

The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. London: George Newnes, 1894.

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Despite, or possibly because of, their extraordinary success, Doyle began to tire of writing the Holmes stories even as he rushed to complete the second series commissioned by The Strand Magazine. His solution was simple: kill off his creation; and he did this in “The Final Problem” which closes this volume. Holmes meets his end in an exciting, unforgettable way: hand-to-hand combat with his nemesis, Professor Moriarty, above the Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland. The world was shocked, and treated Holmes as a real person, with obituaries appearing in newspapers and mourners reputedly wearing black armbands. Doyle went on his way, collecting Holmes royalties, writing fiction, occasional verse, and an account of the Boer War. Bowing to popular demand, he produced The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1901-1902, but Watson’s narrative refers to long-past events before the battle with Moriarty. Finally, Doyle resurrected his hero in “The Adventure of the Empty House” (first published in Collier’s in September 1903), explaining Holmes’s remarkable survival and absence on travels which took him as far away as Tibet before returning to more adventures in London.

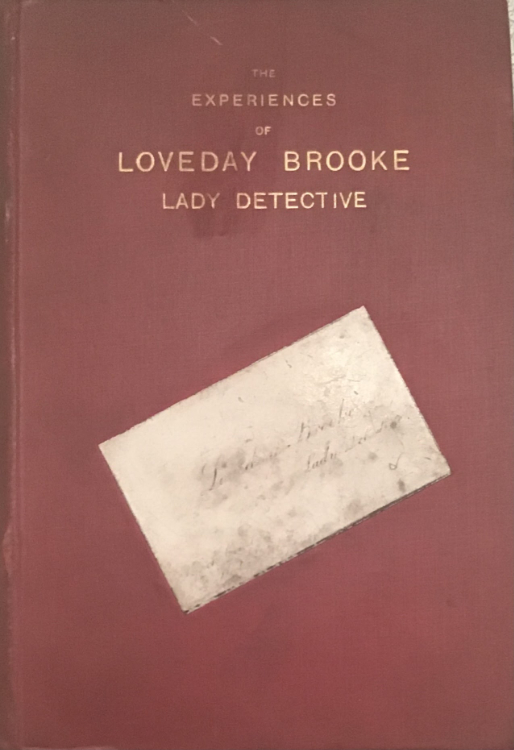

C. L. (Catherine Louisa) Pirkis,1839–1910

The Experiences of Loveday Brooke, Lady Detective. London: Hutchinson & Co. 1894.

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

The 1890s and the years following the turn of the century saw the short story become a major literary form, due to, among other factors, a plethora of new, illustrated periodicals serving a more widely literate and increasingly affluent public which craved reading matter. Crime fiction was especially in demand, with many writers using Doyle’s technique of following a detective through a series of stories which were then collected into books. Imitators and competitors to Sherlock Holmes were legion. Such characters as Arthur Morrison’s Martin Hewitt, R. Austin Freeman’s Dr. Thorndyke, G. K. Chesteron’s Father Brown, and E. C. Bentley’s Trent come to mind. (Not to forget E. W. Hornung’s Raffles, the gentleman thief, who, with his sidekick Bunny, was the flip side of Holmes—but then Hornung was Doyle’s brother-in-law and the first Raffles book was dedicated “To A. C. D. this form of flattery.”) In the age of the New Woman, female sleuths and female authors were not left behind: Grant Allen’s Miss Cayley and Baroness Orczy’s Lady Molly (of Scotland Yard) have their admirers but perhaps the best of their kind was Loveday Brooke, the “lady detective” created by the novelist Catherine Pirkis in the pages of the Ludgate Monthly. Like Holmes, Brooke was brilliant, professional (as shown by the calling card affixed to this book’s front cover), and fully equal, if not superior, to Sherlock Holmes. Contemporary critics considered Pirkis’s plots and writing style better than Doyle’s, as well.

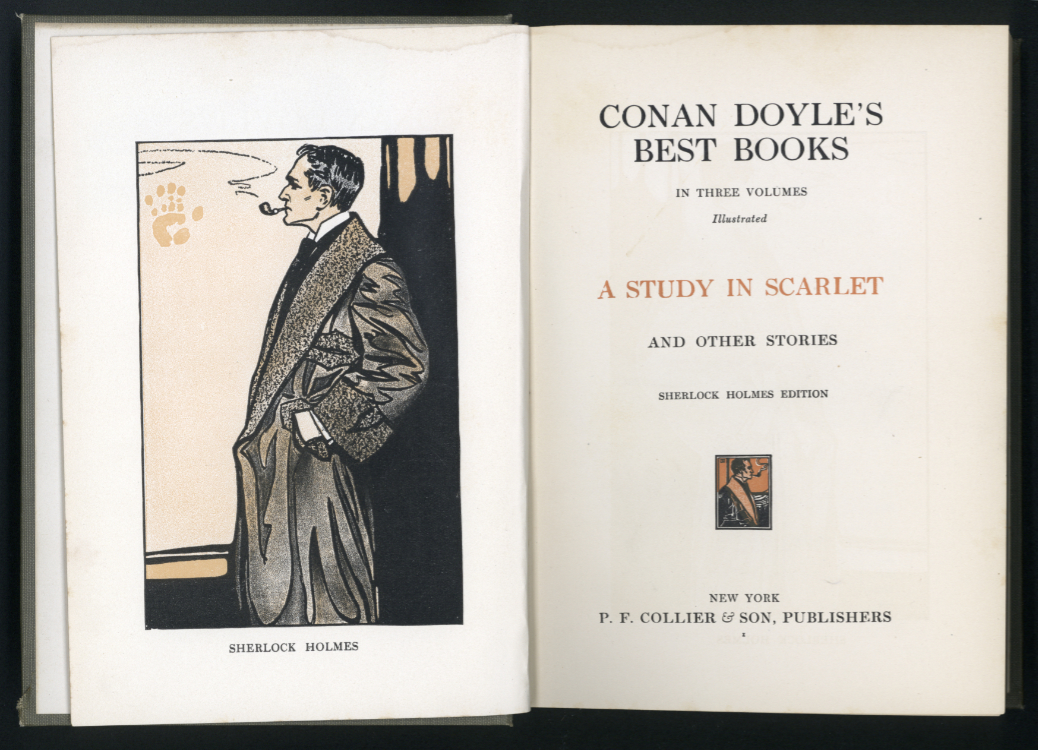

Arthur Conan Doyle, 1859–1930

Conan Doyle's Best Books: In Three Volumes, Illustrated. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1904.

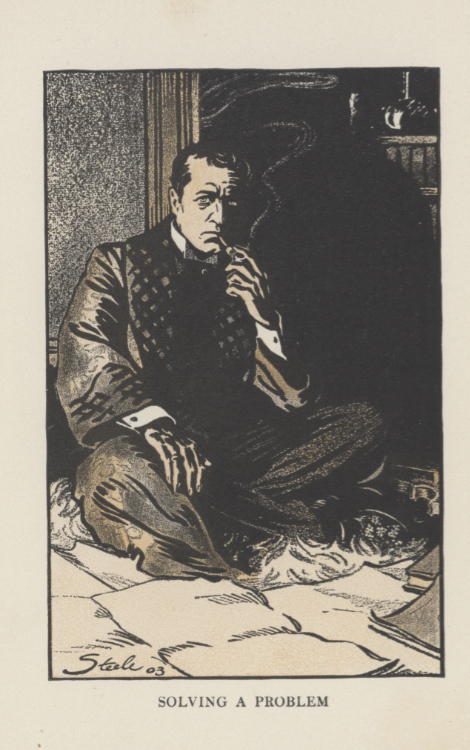

If it was Sidney Paget who gave us the image of Sherlock Holmes wearing a deerstalker cap and Inverness cape (neither of which are in Doyle’s stories), then it was the American artist, Frederic Dorr Steele, who, seeing William Gillette perform in the play version of “A Scandal in Bohemia,” put the consulting detective in a decadent dressing gown. Steele illustrated the stories collected as The Return of Sherlock Holmes when they appeared in Collier’s and the publisher included them in this repackaging of the “canon” as it stood in 1904.

David A. Randall, 1905–1975

The Adventure of the Notorious Forger. Sam Francisco, CA: Randall & Windle, 1978.

Following Doyle’s death in 1930, Holmes seems to have had—and continues to have— a life of his own in the hands of other writers. Some of the “new” adventures, often claiming to derive from an overlooked manuscript left by Dr. Watson, take the form of full-length novels, or, indeed, even whole series of novels. Others are deliberately set in a minor key, aimed at a niche audience and often printed in a collectable format. Randall, an antiquarian bookseller who later became the first head of the Lilly Library at Indiana University, wrote The Adventure of the Notorious Forger for those familiar with the world of rare books. The “notorious forger” is a real person, Thomas J. Wise (1859–1937), the eminent collector and bibliographer who was unmasked in the 1930s as the producer of spurious first editions of such authors as Elizabeth Barrett Browning, William Morris, and Alfred Tennyson. Holmes of course determines that his enemy Professor Moriarty, Moriarty’s henchman Colonel Sebastian Moran, and Wise are one and the same. (Special Collections has significant holdings related to Thomas J. Wise and his associates in the Frank W. Tober Collection of Literary Forgery.)

Arthur Conan Doyle, 1859–1930

The Hound of the Baskervilles. San Francisco: Arion Press, 1985.

Founded in 1947 and following in the tradition of the famed Grabhorn Press, the Arion Press in San Francisco has produced celebrated fine press editions of classics and avant-garde literature for nearly seventy-five years. The books were (and are) designed by the distinguished printer, Andrew Hoyem, and nearly always are collaborations with well-known artists. This edition of The Hound of the Baskervilles is unusual because the illustrations do not specifically depict scenes from the novel; instead, the photographs by Michael Keenan seek to evoke the wild moors of Dartmoor where the adventure takes place.

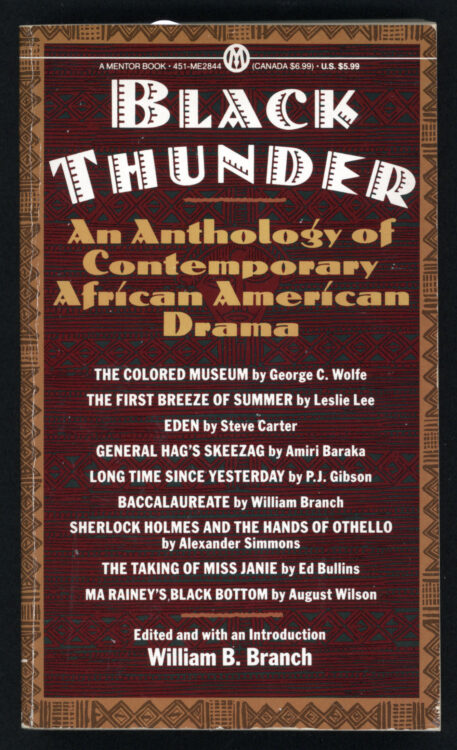

William B. Branch,1927-2019

Black Thunder: An Anthology of Contemporary African-American Drama: Edited with an Introduction by William B. Branch. Mentor, 1992.

Edited by William B. Branch, a leading Black playwright, Black Theater includes Sherlock Holmes and the Hands of Othello: A Drama in Two Acts by Alex Simmons. First produced by Westbeth Theatre in New York in October 1987, the play tells of Holmes solving a complicated case in which the daughter of famed nineteenth-century Black Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge is visited by a family curse. Simmons is a distinguished writer, arts educator, playwright, and producer, the founder of the annual Kids Comic Con, and founder and curator of the Color of Comics Exhibition. He also served on the board of the New York State Alliance for Arts and Education for five years; is a consultant for the Christopher Barron Live Life Foundation; and is affiliated with the Museum of Comic & Cartoon Art.

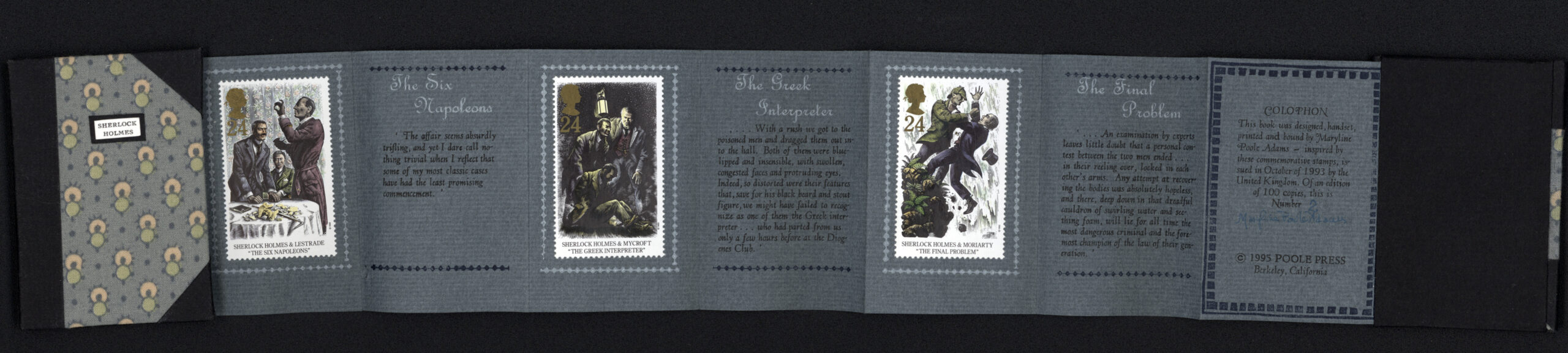

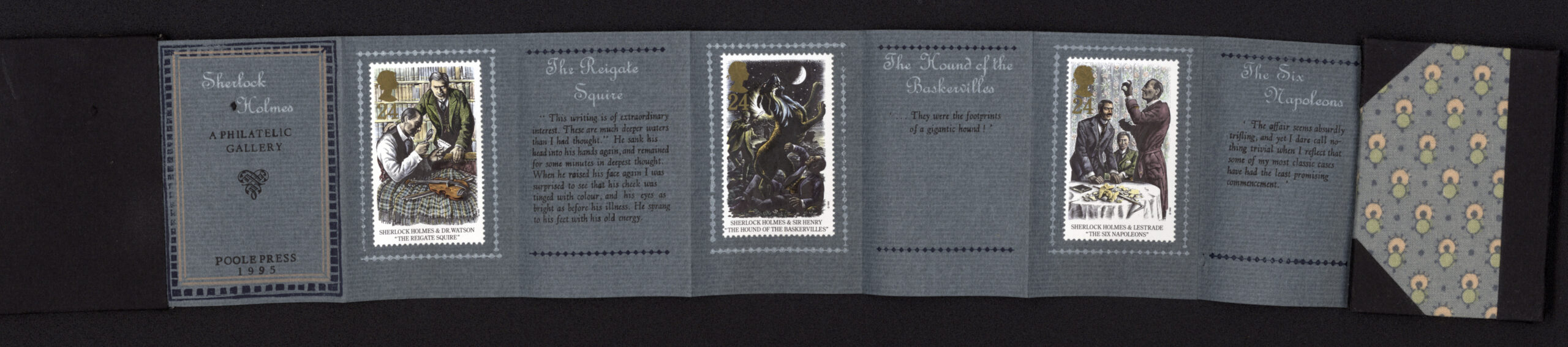

Sherlock Holmes: A Philatelic Gallery. Berkeley, CA: Poole Press, 1995.

Marnie Flook Miniature Book Collection

“Designed, handset, printed and bound by Maryline Poole Adams,” this unusual miniature artist’s book incorporates actual postage stamps, issued in October 1993 by the British Post Office to commemorate the century of the publication of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

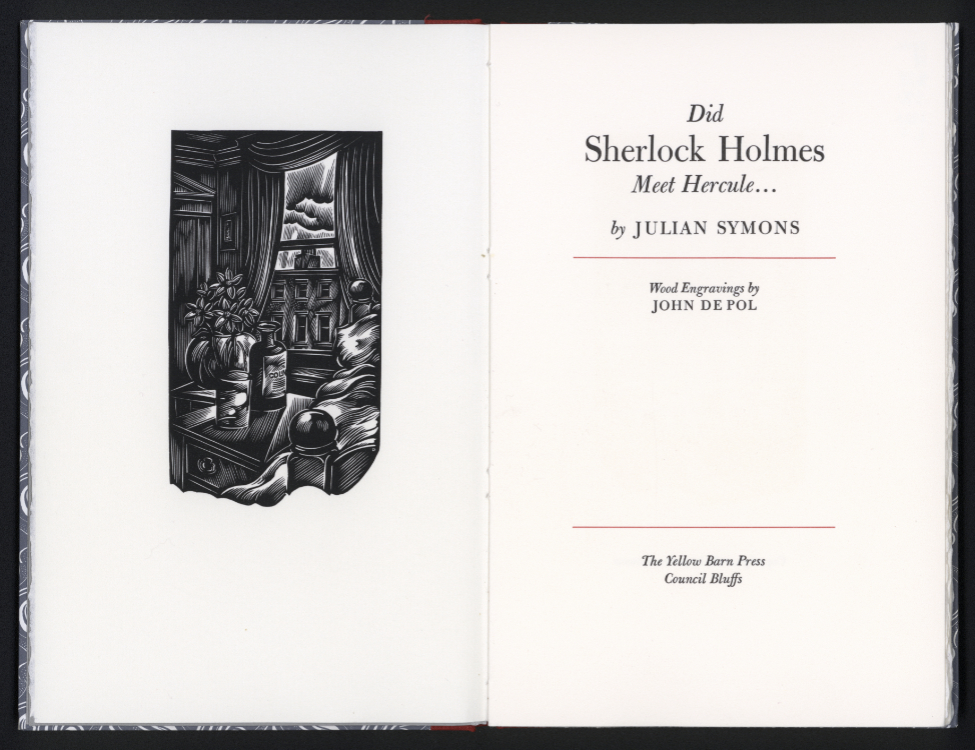

Julian Symons, 1912–1994

Did Sherlock Holmes meet Hercule…: Wood Engravings by John De Pol. Council Bluffs, IA: Yellow Barn Press, 1988.

In this skit in which Sherlock Holmes meets up with the world’s other greatest consulting detective, Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot, the crime writer (and writer on crime) Julian Symons continued the long history of imagining Holmes’s interacting with fictional and historical figures. The tradition began early, when Maurice Leblanc’s “Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late,” was collected in Arsene Lupin, Gentleman Burglar in 1905. Since then, Holmes has had encounters with, to name just a few names, Dr. Jekyll, Dracula, Frankenstein, Tarzan, Alice (in Wonderland), Harry Potter, and Tom and Jerry. He has also been depicted alongside nonfictional historical figures, some of whom, such as Oscar Wilde, Israel Zangwill, and Harry Houdini, were known to Arthur Conan Doyle. Perhaps the most memorable of all these relationships was the one recorded in Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven Percent Solution in which Sigmund Freud gets to the root of Holmes’s troubled psyche through hypnosis. Beautifully printed letterpress, Did Sherlock Meet Hercule … contains two illustrations by John De Pol, one of the American masters of wood-engraving of the twentieth century and a regular collaborator with Neil Shaver’s Yellow Barn Press. De Pol’s extensive archive is held by Special Collections.