First, Elizabeth Barrett had a passion for poetry. Then, Robert Browning had a passion for Elizabeth Barrett’s poetry. Soon, Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning developed a passion for each other. Eventually, defying her tyrannical father, they eloped to Italy in 1846 and lived happily, if too briefly, ever after with their only child, “Pen” (1849–1912). Almost every late-Victorian writer grew up with this story and saw in it the ideal heterosexual romance. In the twentieth century, Rudolf Besier (1878–1942) breathed new life into it with his play The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1930), but Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) reveled in “queering” it, with Flush: A Biography (1933), and made the deeper love that between Elizabeth and her dog. On display here is a photograph of Elizabeth—a copy of a daguerreotype by Macaire. Alongside it is one of her with “Pen” (Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning)—an image taken in Rome and sent by the Brownings to the Pre-Raphaelite writer William Michael Rossetti (1829–1919).

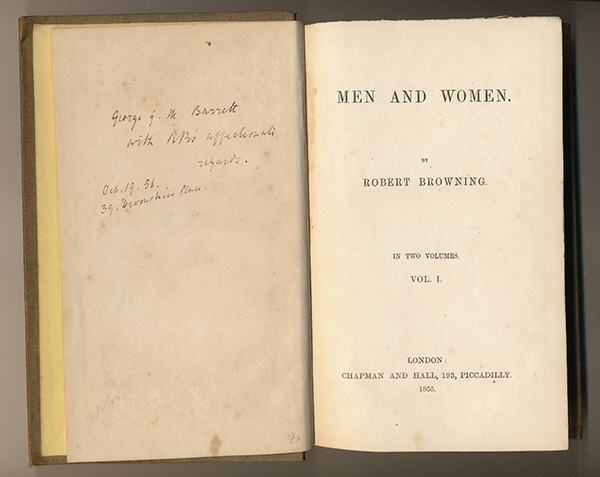

Dramatic monologues proved the perfect vehicles through which Robert Browning could not merely represent, but inhabit, the passions of others in poetic form. Some of those passions—especially the ones that involved the aspirations or frustrations of musicians and artists—were feelings that he could share as a creative figure still on the cusp of achieving renown, but not there yet. He inscribed this copy of Men and Women—which contained poems with Italian settings, such as “Fra Lippo Lippi” and “A Toccata of Galuppi’s”—just as he and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, who had eloped in 1846, were at the end of a six-week-long visit to London and were about to leave for Florence. The recipient was George Moulton Barrett (1816–1895), one of Elizabeth’s brothers and the first family member to accept her marriage, to which their father would never be reconciled.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828–1882. Poems: Privately Printed, July to Decr. 1869. [London: Strangeways and Walden, 1869–1870]. Alice Boyd’s bound proofs for Rossetti’s 1870 Poems.

After decades in which he was primarily a painter, Dante Gabriel Rossetti turned passionately and obsessively to writing new poems and reworking old ones in the two years preceding the publication of Poems (1870). To revise the older ones required, quite horrifyingly, the exhumation in 1869 of a notebook containing the sole manuscripts of some of them—a notebook he had rashly placed in the coffin of his wife, Elizabeth Siddall (1829–1862), before she was interred at Highgate Cemetery. The official publication of Poems was preceded by a long succession of proofs. Shown here was one presented by Rossetti to the painter Alice Boyd (1825–1897), who studied (and was in an adulterous relationship) with Rossetti’s fellow Pre-Raphaelite, William Bell Scott (1811–1890). While preparing Poems, Rossetti stayed with Boyd and Bell Scott at Penkill Castle, her home in Scotland. This copy belonged to Simon Nowell-Smith (1909–1996), the Secretary of the London Library and Mark Samuels Lasner’s chief mentor in book collecting. It is open to one of the recovered poems, “Jenny,” where a male speaker imagines the unspoken thoughts of a prostitute and considers the effects on women of dividing them into the “pure” and the “fall’n.”

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1828–1882. Poems. London: F. S. Ellis, 1870. Author's presentation copy to Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, inscribed “To Mdme Bodichon with D. G. Rossetti's friendly regards April 1870.”

She was a talented painter, but her passion for women’s rights drove Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891) to polemical writing and to political activism. As one of the founders of Girton College and an early supporter of women’s suffrage, she led campaigns for social justice and moved in radical circles. Most famous for her intimate friendship with George Eliot, she was also close to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his model Elizabeth Siddall, who became a poet and artist herself and who married him in 1860. They had stayed in 1854 with Bodichon at her country house, where she drew the delicate, idealized portrait of Siddall included in this exhibition. After Rossetti published his 1870 volume Poems, making use of texts from the notebook he had buried in Siddall’s coffin in 1862 and exhumed seven years later, he inscribed this copy to Bodichon.

Oscar Wilde. 1854–1900. On the Sale by Auction of Keats’ Love Letters, autograph manuscript, [November–December 1885].

Like a number of Aesthetic Movement poets and critics, Oscar Wilde was a passionate devotee of the works of John Keats (1795–1821). The public offering of several of Keats’s intimate letters to Fanny Brawne (1800–1865) so offended Wilde that he composed this sonnet in protest against “the brawlers of the auction mart.” His sense of outrage, however, did not get in the way of his own bidding at the 1885 sale. Wilde enclosed this manuscript in a letter—also in the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection—to the editor and author William Sharp (1855–1905), who published the poem in a volume titled Sonnets of This Century (1886).

W. B. (William Butler) Yeats, 1865–1939. The Wanderings of Oisin: And Other Poems. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co., 1889. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed “Miss May Morris with the good wishes of W. B. Yeats Jan 19th 1889.”

That passions are fleeting and none, including love, are eternally fulfilling is a theme running through the title poem in this, W. B. Yeats’s first book of poetry. Critics have often complained of weakness in this early work about the pagan Oisin’s three-hundred-year-long quest, seeing Yeats’s epic as too indebted—despite its use of Celtic materials—to Pre-Raphaelite models. William Morris had welcomed the young Irish-born poet into his home, and Yeats was indeed influenced by him; so were his two sisters, who were close to Morris’s daughter, May (1862–1938), and who worked alongside her in the Arts-and-Crafts Movement. Yeats presented this copy of The Wanderings of Oisin to May Morris, hoping that her father would read it. As he later reported in The Trembling of the Veil (1922), Morris did so and began to praise it, “and he would have said more had he not caught sight of a new ornamental cast-iron lamp-post and got very heated upon that subject.”

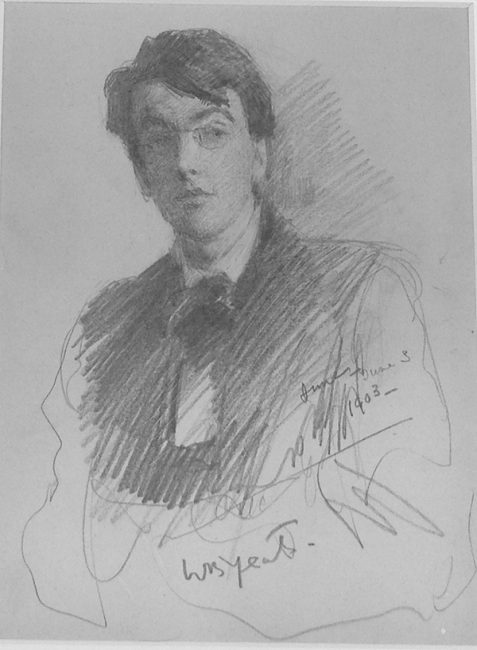

There was scarcely a more prodigiously gifted late-Victorian family in the whole of the British Isles than that of the Irish-born artist John Butler Yeats. Among his six children were a painter; a printer and publisher; an Arts-and-Crafts embroiderer; and, of course, the chief poet and dramatist of the Celtic Revival, William Butler Yeats (1865–1939). By 1903 (the year of this portrait sketch), W. B. Yeats had turned from his earlier involvement with London-based Aesthetes, through the Rhymers’ Club and Yellow Book circles, to focus more intently on Irish nationalist projects, including the development of an Irish theatre. Also by 1903, he had met the Irish American collector John Quinn (1870–1924), who became a financial supporter of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, as well as a passionate acquirer of Yeats’s work. Quinn, who lived in New York City, owned this drawing by John Butler Yeats of his son, which captured beautifully the poet’s magnetism and glamour.