John Ruskin, 1819–1900. The Stones of Venice: With Illustrations Drawn by the Author, London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 1851–1853. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed in v. 1 “Thomas Carlyle. Esq. With the Author’s sincere and respectful regards.”

Instructing others was John Ruskin’s passion—teaching them to rage, as he did, against the shoddy goods that resulted from mass production, the degradation of workers’ lives, and the destruction of Nature by industrialism. To reach them, he used public lectures, his platform as the Slade Professor of Fine Arts at Oxford University, and books such as The Stones of Venice. In the latter, he retrained both the political understanding and the aesthetic vision of his readers, encouraging them to find beauty in the architectural details of Gothic cathedrals through his careful drawings. He presented this copy to the critic Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) who wittily called it a “most true and excellent Sermon in Stones” and, more seriously, “the best piece of School-mastering in Architectonics, from which I hope to learn in a great many ways.” Later, this copy was owned by Louisa, Lady Ashburton (1827–1903)—Carlyle’s friend and fellow Scot, who became the long-time intimate companion of the American expatriate sculptor, Harriet Hosmer (1830–1908).

Four years before receiving her first camera as a present in December 1863, Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) was the grateful recipient of another important gift: this copy of Idylls of the King (1859) in a special red morocco binding, with an inscription by her friend Alfred Tennyson. Although photography—always done for the sheer love it, never as a professional career—would become her consuming passion, she remained enthusiastic about both Tennyson and his poetry. In 1865, she shot a famous image of him, known as The Dirty Monk, which is also in the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. When Tennyson asked her, in 1874, to create photographic illustrations of scenes from his Arthurian Idylls, she produced a series that was both painterly and theatrical. (One of her works, depicting Lancelot and Guinevere, is also in this exhibition.) Tennyson’s presentation copy of Idylls is accompanied by a letter—not to Cameron, but to the Boston firm of Ticknor and Fields, from 1858. In it, Tennyson deliberately misleads the publishers, insisting that he would never write on the subject of King Arthur. He did, of course, publish Idylls—his representation of Victorian concerns in medieval guise—less than a year later. Many British authors were evasive, if not hostile, when dealing with American publishers, because the latter so often pirated their works and paid no royalties.

Except in very “advanced” circles, real-life contemporaries who loved outside of marriage were subject to being shunned, publicly humiliated and, if they were women, to having their children taken from them. Nonetheless, the Victorians were fixated on exploring adulterous passion in medieval romance. The character of Guinevere was a particular focus for poets. William Morris wrote a “Defence” of her, while she was cast as the force whose betrayal of Arthur with his knight, Lancelot, brought down the kingdom in Alfred Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. For a special version of the latter in 1874, Tennyson asked Julia Margaret Cameron, his friend and neighbor on the Isle of Wight, to supply photographic illustrations. Turning photography into an art form that could compete with painting was her passion, and she took up this challenge enthusiastically. She dressed friends, relatives, and even her household staff in pseudo-Arthurian costume and shot each image dozens of times, determined to achieve perfection.

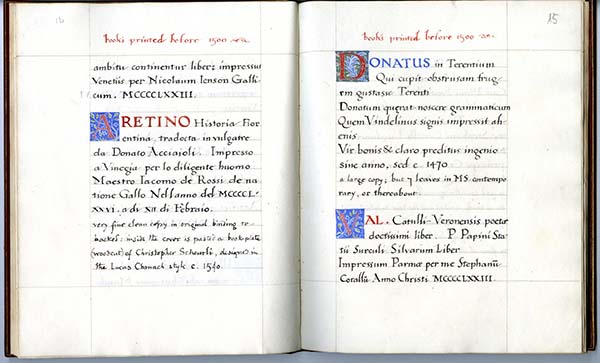

When he was not attending meetings of the Hammersmith Socialists, producing and selling wallpapers and other Aesthetic household furnishings, composing poetry, designing stained glass windows, lecturing on art and social reform, and exercising his talents in a dozen other directions, William Morris studied medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts and practiced calligraphy. This is a unique volume containing eighteen pages of an incomplete project, in which Morris began to catalogue the rare books in his library, bound together with a three-page-long fragment of his translation of The Tale of Haldor, an Icelandic legend. After Morris’s death, it was given by his widow, Jane Morris (1839–1914), to Sydney Cockerell (1867–1962), who had worked for Morris as his secretary, and who went on to a distinguished career as Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum.

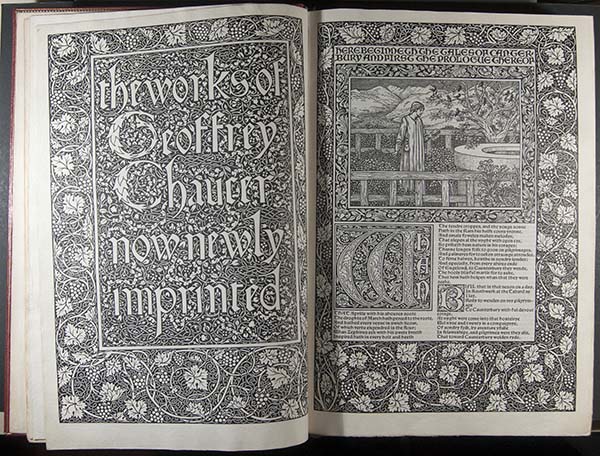

For collectors of Victorian literature or of exquisite books from any period, this is the prize among prizes: the Chaucer designed by William Morris (1834–1896), illustrated by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones, and printed by Morris at his Kelmscott Press. It was the capstone of Morris’s career—the fulfillment of his desire to pay tribute to medieval ideals while realizing his own aesthetic vision. To Morris, a passionate Socialist, dreaming was a political act: a means to transcend and transform the ugliness of everyday Victorian life, with its industrial blight and social inequality. This book was for him quite literally a dream come true, and he hoped that it would be an inspiration to others, encouraging them to work toward creating a new world that would be its equal in beauty.

Owning the Chaucer was a goal always tantalizingly out of reach for Mark Samuels Lasner, as he assembled rare and unique Victorian materials over a period of more than forty years. In 2016, however, he acquired this wonderful copy. Only three months before his death, William Morris had presented it to the artist Robert Catterson Smith (1853–1938), who played a crucial role in assisting Morris and Burne-Jones with the book’s illustrations. Now it serves as the centerpiece of the remarkable collection bearing his name that Mark Samuels Lasner has donated to the University of Delaware Library.

Sir Edward Burne-Jones bridged the divide between the mid-century Pre-Raphaelites and the late-Victorian followers of the Aesthetic Movement. The worship he felt for the Middle Ages, and which he shared with other Pre-Raphaelites, by no means precluded his loving the art of Classical Greece and Rome, which was a passion, too, among the Aesthetes. But whether he was painting a figure from the Arthurian legends or a Greek goddess, his women were much the same: long-limbed, long-necked, and graceful yet stately. This watercolor of the Muse of Poetry, who looms over Virgil in almost intimidating fashion, belonged to Burne-Jones’s son-in-law, J. W. (John William) Mackail (1850–1945). Mackail, Professor of Poetry at Oxford, was a passionate classicist who translated Virgil’s Aeneid and published studies of his poetry, as well as, in 1899, the first biography of William Morris.

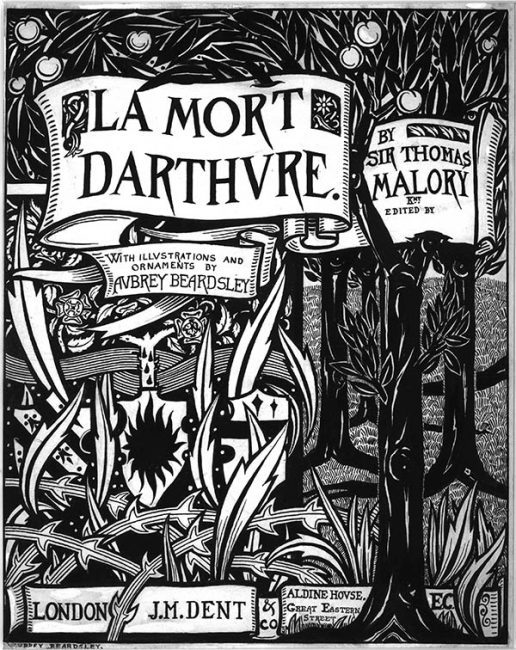

Medievalism had been a passion among Victorian artists for decades—first among the Pre-Raphaelites and then the Aesthetes. Well into the 1890s, it continued to inspire the Decadents, though it took on, quite literally, a different shape. In the hands of Aubrey Beardsley, for instance, allegedly “medieval” decorative forms became both more sinuous and spikier, with decidedly Japanese-influenced touches. Illustrating the publisher J. M. Dent’s new edition of Le Morte Darthur was Beardsley’s first major commission, and his inexperience shows in this design. The artist has misspelled the book’s title as La Mort Darthure, and the lettering throughout has required some touching up and correction.