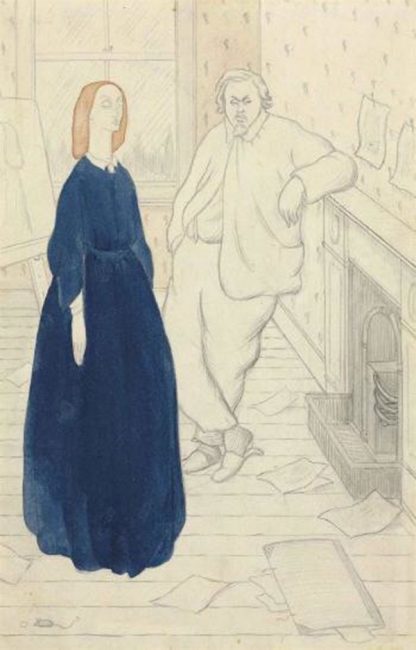

Confounding viewers’ expectations was a prospect that delighted Max Beerbohm. In this study for a drawing that later appeared in Rossetti and His Circle (1922), his comic reimagining of the lives of the Pre-Raphaelites and their Aesthetic Movement disciples, he returns to the mid-nineteenth century and to a key scene in the history of art, involving Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) and Elizabeth Siddall (1829–1862; whom Rossetti rechristened with the spelling “Siddal”). The passionate romance between the volatile Rossetti, who was obsessed with his model and muse, and the working-class woman who rose from selling hats in a millinery shop to be an artist herself has been rendered bloodless and cold. Both lovers look bored witless. Both, too, look like haughty aristocratic figures, instead of ardent bohemians who broke Victorian conventions with their cross-class alliance and marriage in 1860.

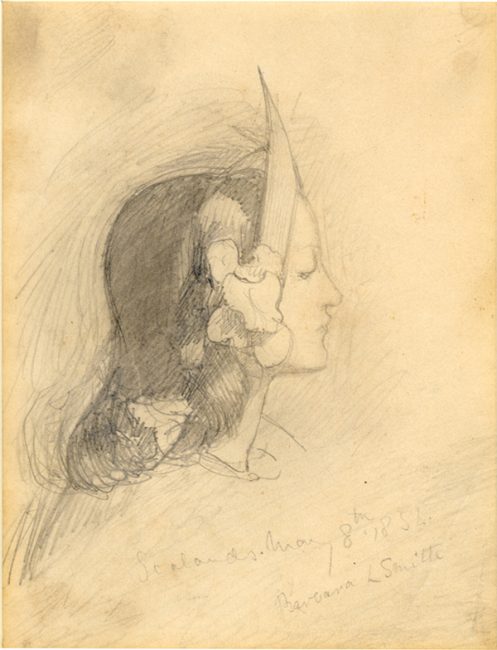

Pale, wan, and languid as she often appears to be in artists’ renderings of her—and as she probably was in life, given her ill health and regular doses of opiates—it is easy to forget that Elizabeth Siddall was also a creative figure. In 1978, Mark Samuels Lasner and Roger C. Lewis brought new attention to this other aspect of her, with their edition of Poems and Drawings of Elizabeth Siddal (“Siddal” was how D. G. Rossetti preferred to spell her name). The subjects she wished to treat, whether verbally or visually, were melancholy ones: autumnal scenes, the loss of love, or, in the case of her drawing titled The Woeful Victory, a medieval tableau with an androgynously beautiful knight who has fallen in chivalric combat. Siddall’s own work is flanked here by two portraits of her. We see her as she looked to the artist Barbara Bodichon, a passionate advocate for the political and educational rights of women, who has turned Siddall’s floral headdress into a kind of crown and its wearer into a queenly figure. We also see her, however, through the eyes of Rossetti as a beloved invalid—frail and like a shriveled flower, with its petals closing in upon itself.

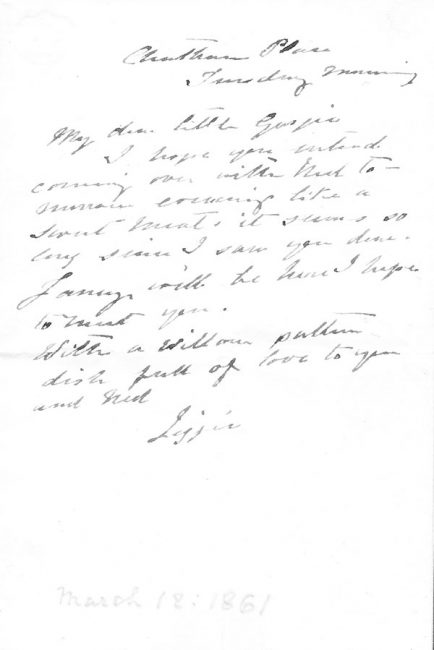

Drawn and painted by the Pre-Raphaelite circle and adored by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in particular—whom she allowed to change her name to “Siddal,” and whom she married in 1860—Elizabeth Siddall is remembered today as the focus of male artists’ passions; yet she remains an enigmatic, if not elusive, figure. She lived for only thirty-two years and left behind a small body of work in poetry and the visual arts, but little in the way of correspondence. This is among the few letters of hers that is known to have survived. Unfortunately, it reveals nothing about the passions that animated her, though it does show that even the rebellious Pre-Raphaelites observed certain Victorian norms, such as relying on wives to make social arrangements. Siddall writes to Georgiana Burne-Jones (1840–1920), the wife of the painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), to arrange a social occasion involving members of their Pre-Raphaelite circle, including Jane Burden Morris (1839–1914).

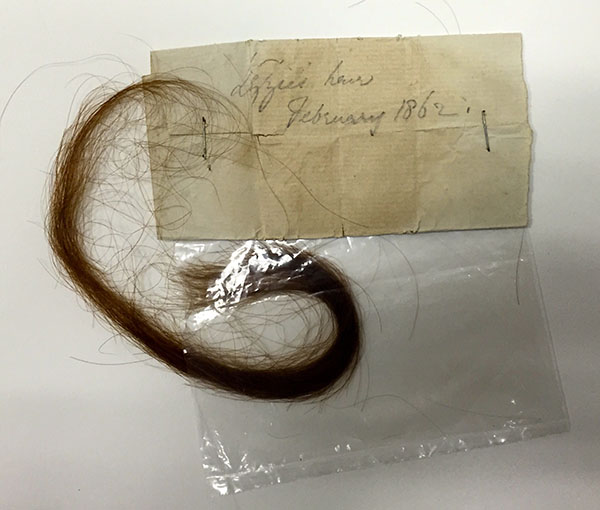

YES, THIS IS AN ACTUAL LOCK OF ELIZABETH SIDDALL’S HAIR!

In a fit of grief following the death of his young wife and muse from a drug overdose, Dante Gabriel Rossetti placed in the coffin containing her body the sole copy of his manuscript of unpublished poems. That story is familiar to everyone who knows the lurid lore surrounding Elizabeth Siddall. Less well known is that, before burying her, he cut off a lock of her red hair—the hair he had loved ardently, indeed fetishistically, and had apotheosized so often in his paintings. Accompanying the lock is a note in Rossetti’s hand, identifying it as “Lizzie’s hair.” He preserved the hair throughout his lifetime, and it remained in the Rossetti family until his niece, the writer Helen Rossetti Angeli, gave it to the American-born Pre-Raphaelite scholar William E. Fredeman (1928–1999), from the sale of whose archive Mark Samuels Lasner acquired it. Although a small object, this lock quite literally embodies an entire world of Pre-Raphaelite passions.

In La Belle Iseult (1858), his sole attempt at painting the working-class model whom he married a year later, William Morris turned Jane Burden (1839–1914) into a medieval mannequin, wooden and awkwardly jointed. Of this effort, the story goes, he wrote apologetically, “I cannot paint you but I love you.” Morris’s dear friend D. G. Rossetti, on the other hand, could both paint her and love her, so he did. As this portrait attests, he could also draw her, capturing the voluptuousness of her body in sleep and portraying for all to see the sensuality of their extramarital relations. Rossetti and William Morris stayed close, while Rossetti and Jane Morris got closer. The polyamorous passions of the Pre-Raphaelites were radical in their own day and remain so even in ours.

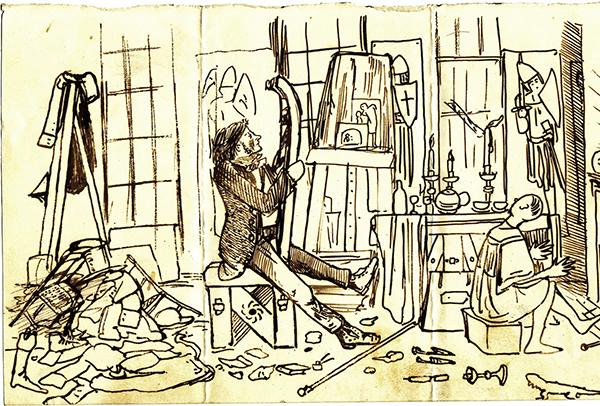

Of all the Pre-Raphaelite artists, none had a better sense of humor than Sir Edward Burne-Jones. Although he is famous now for his paintings of idealized Classical and medieval maidens, he was in fact a compulsive cartoonist. The Mark Samuels Lasner Collection contains a number of his sly comic sketches, done for his own amusement and for circulation among friends. These include drawings of plump, squeezable-looking wombats (inspired by the two who lived briefly in D. G. Rossetti’s garden); caricatures of his family and social circle; and this revealing self-caricature. It shows him at work in his studio, in the house that he shared at the time with William Morris. Mark Samuels Lasner acquired this sketch almost accidentally, when it turned up unadvertised in a portfolio of sketches that arrived with the Burne-Jones visitors’ book also included in this exhibition.

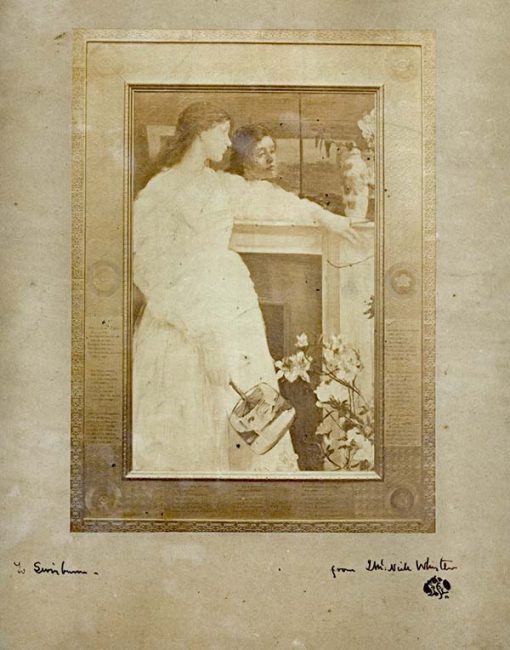

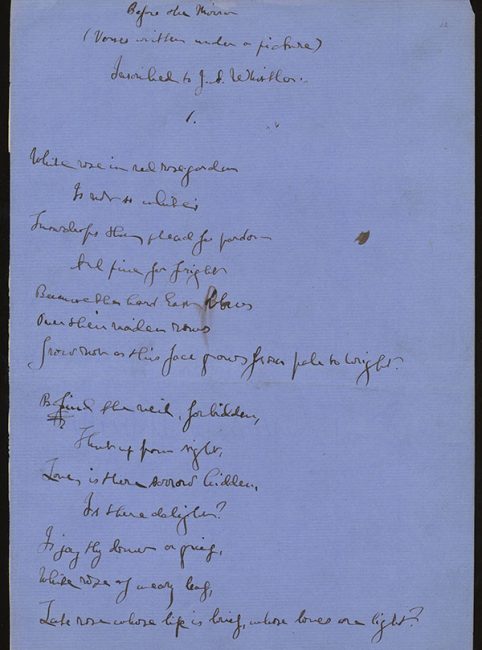

Passions of many sorts circulated throughout the social networks of the Pre-Raphaelites and their successors, the Aesthetes and Decadents, informing work in media both old and new. J. M. Whistler—the American artist and Dandy, who settled in London in the 1850s—translated his passion for the red-haired model Joanna Hiffernan (1843–1904) into several portraits, including Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl. The poet A. C. Swinburne’s enthusiasm for this painting inspired him to compose “Before the Mirror: Verses Written Under a Picture,” and lines from that poem were then pasted onto the frame. Here is the manuscript of the poem, which Swinburne inscribed and presented to Whistler. With it is a contemporary photograph of the framed painting that Whistler gave to Swinburne, after signing the image with the abstract butterfly that he also used when signing his own artworks. Although some Victorian artists were hostile to photography, Whistler was not. Swinburne, of course, became an avid collector of photographs, as we see from his album of cartes-de-visite (on view in this exhibition).