Algernon Charles Swinburne, 1837–1909. Algernon Swinburne’s photograph album, [1867].

After the publication in 1866 of his Poems and Ballads, the very name of Algernon Swinburne signified, for many conservative Victorians, unlawful if not repellent passions. In his poetical works, he alluded to a number of these, including sadomasochism, flagellation, and same-sex relations; in real life, he added to them a desire to run naked and to drink until he passed out. Some people might have guessed that he was an aficionado of pornographic photographs, but few would have imagined that among his passions was also one for collecting cartes-de-visite. It began when his friend and fellow participant in outrageous acts, George Powell (1842–1882), gave him a photograph album in 1867. Swinburne eagerly filled it with images of those he knew or admired. Here, it is open to a portrait of Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) by the photographer Félix Nadar (1820–1910); of George Powell with Eiríkr Magnússon (1833–1913), who worked with William Morris in translating Icelandic sagas; of the artist James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903); and of George Powell’s pet monkey, who slept in his bed and with whom his relationship was allegedly intimate.

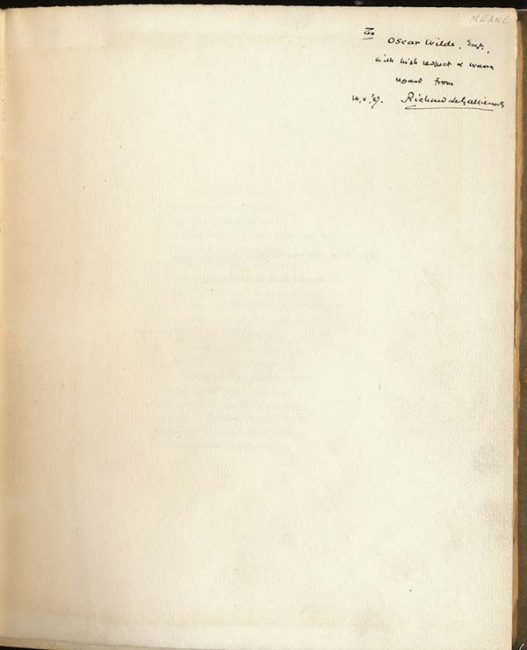

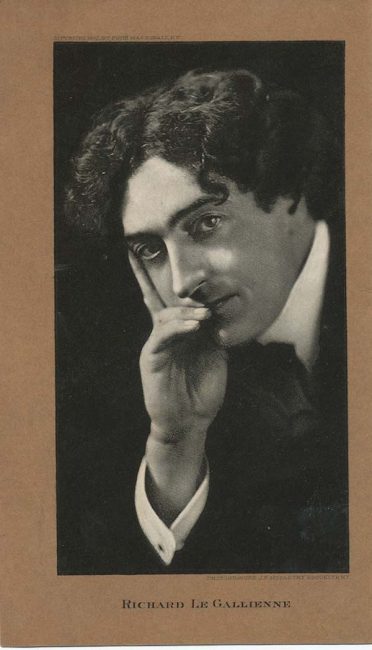

Did he . . . ? Did they . . . ? Scholars disagree over whether the relationship between Oscar Wilde and his acolyte, the poet and critic Richard Le Gallienne, was merely one of platonic passion and shared devotion to Beauty or something more carnal. Le Gallienne—born in Liverpool as “Richard Gallienne,” without the romantic-sounding “Le”—had worshiped Wilde ever since the evening of 9 December 1883, when the Irish Aesthete gave a lecture in Birkenhead about his American tour of the year before. To the seventeen-year-old budding writer, unhappily employed in an accounting firm, Wilde was a guiding star. Le Gallienne affected Aesthetic dress, grew his hair, produced Aesthetic verse, and plotted his escape from the world of commerce to the sphere of Art (capital “A”). After the Liverpool-based printer John Robb issued his first book, Le Gallienne sent this inscribed copy of it to Wilde, hoping that it would lead to an invitation to meet his idol. It did. What happened afterwards between the very beautiful young poet, who attracted women and men alike, and his mentor in Aestheticism is a matter for speculation.

Thomas Hardy, 1840–1928. Tess of the D’Urbervilles: A Pure Woman Faithfully Presented. London: J. R. Osgood, McIlvaine, [1891]. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed in v. 1 “To Frederic Harrison from Thomas Hardy with all wishes for the New Year December 1891.”

Some readers were so outraged by the claim that Tess Durbeyfield—who is raped while asleep, bears a child out of wedlock, and later murders her rapist—was nonetheless a “pure woman,” as the novel’s subtitle asserted, that they condemned Hardy’s work as immoral and as a sign of the corruption blowing across the Channel from France in the form of Naturalist fiction. That was not the opinion, however, of Hardy’s long-time friend, the critic and social reformer Frederic Harrison (1831–1923). An adherent of the philosophy of Positivism, in which Hardy was also interested, Harrison became a passionate defender of Tess, which he found to be not only like “a Positivist allegory or sermon” in its advocacy of empathy, but “a very beautiful book.” Certainly, it was literally a beautiful book, with an elegant cover design by Charles Ricketts (1866–1931), who lived in a domestic partnership with the artist and Aesthete, Charles Shannon (1863–1937). This copy, inscribed by Hardy to Harrison, is one of only five known to have been presented by the author.

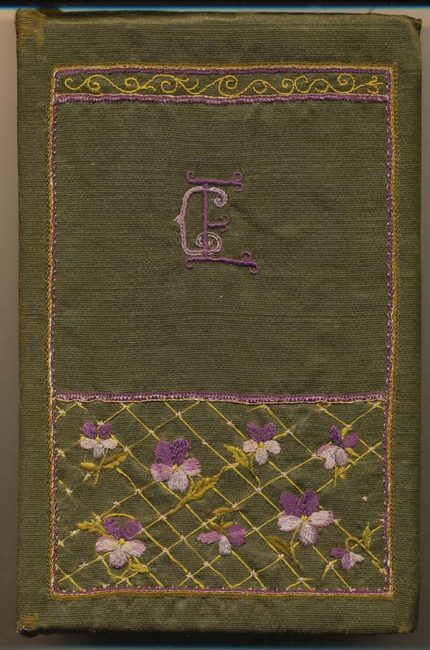

“A Cross Line,” the opening story of this 1893 volume, sent straitlaced critics into a frenzy with its non-judgmental depiction of an educated, middle-class woman who has an adulterous relationship, while fantasizing about dancing onstage and using her sexuality to control crowds of admirers. Nonetheless, thousands of bookbuyers—especially female readers—sensed a kindred spirit behind the masculine pseudonym of “George Egerton” and associated its author with the burgeoning feminism of the British “New Woman” literary movement. The writer was indeed an unconventional woman, but an Irish one, born Mary Chavelita Dunne, who took her pen name from her mother (Isabel George) and her husband (Egerton Clairmonte). Having migrated to England, where she lacked both money and contacts, she was dependent on her publisher at the Bodley Head, John Lane (1854–1925), whom she tried to draw closer through seductive gestures and offerings of personal revelations. She filled this presentation copy of Keynotes with annotations for his eyes only, linking the fiction to facts from her own passionate experiences with men, and also embroidering a green cover for it that substituted an image of her own devising (flowers and her initials) for Aubrey Beardsley’s design on the original binding (a female puppet worked by a Pierrot).

Grant Allen, 1848–1899. The Woman Who Did, corrected typescript, [1893]: with autograph manuscript reader’s report from Richard Le Gallienne, October 1893, and autograph letter from George Moore to John Lane, 4 November [1893].

After John Lane (1854–1925), co-founder of the Bodley Head press, broke with his business partner Elkin Mathews (1851–1921) in 1894, he made a specialty of controversial, sexually daring fiction. His chief vehicle was the Keynotes Series, named for the 1893 volume of feminist short stories by “George Egerton,” with covers and title-page designs by Aubrey Beardsley. Even Lane, however, hesitated before adding to this series Grant Allen’s novel, which had a subject so inflammatory that its title ended in mid-thought (The Woman Who Did What?) and left the rest to readers’ imaginations. Grant Allen was a radical social reformer, but his notion of the aims of contemporary “New Women” was inaccurate, focused too narrowly on their alleged desire for Free Unions with men. Herminia Barton, protagonist of Allen’s novel, becomes a social martyr because of her insistence upon a non-binding relationship with a man who then dies, leaving her pregnant and unmarried. While deciding whether to publish the text shown here in the form of a corrected typescript, Lane turned to two writers who were no strangers themselves to passion outside of marriage or to courting the ire of conservative audiences: the English poet Richard Le Gallienne (1866–1947) and the Irish novelist George Moore (1852–1933). When Lane did at last issue Allen’s sensational novel in 1895, it became a bestseller.

His passion not merely for literature but for books as physical objects made Richard Le Gallienne a natural ally of the bibliophilic Elkin Mathews and John Lane, who started the Bodley Head press together. As the founders’ business relationship came apart, Le Gallienne threw in his lot with the more entrepreneurial Lane, serving as publisher’s reader and, through his regular column of book reviews for the Star, as a steady promoter of new publications. Le Gallienne was also among Lane’s most prolific authors of poetry and prose and one of his closest friends. They were visiting New York together when the awful news broke of Oscar Wilde’s arrest in April 1895 for “gross indecency” with men. Worse yet, one of Lane’s clerks (Edward Shelley) had testified that, while employed at the Bodley Head’s Vigo Street offices, he had met Oscar Wilde there and become his lover. The moral backlash following the Wilde trials appalled Le Gallienne. After 1900, he returned to the U.S. to live for several decades before, like Wilde, spending his final years in France.

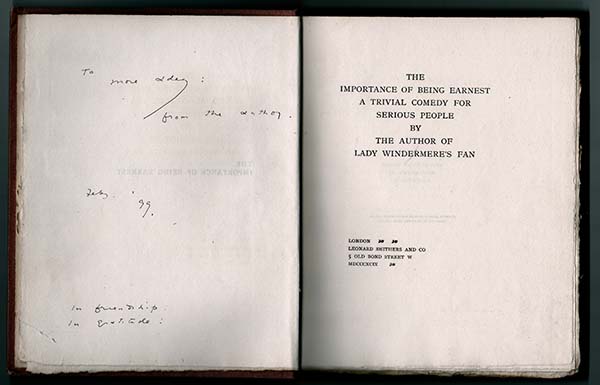

In this, the wittiest comic play of the nineteenth century (some might say in the history of the English stage), Oscar Wilde demonstrated that there was no passion that could not be made to seem ridiculous, whether jealousy, anger, or especially heterosexual romantic love. After Wilde’s prosecution for the crime of “gross indecency” with men, John Lane (1854–1925), his publisher, panicked and withdrew from print all of his works, even as his plays were being pulled from the London stage. The text of Earnest, which had opened at the St. James’s Theatre on 14 February 1895 and had its run cut short, was not published until 1899, two years after Wilde’s release from prison, when Leonard Smithers (1861–1907) issued it without Wilde’s name on the title page. This copy was inscribed by Wilde to (William) More Adey (1858–1942), the art critic and beloved member of a loyal inner circle of supporters that included Robert (“Robbie”) Ross (1869–1918), Wilde’s literary executor, with whom Adey later established a longterm romantic partnership.

The Adult: The Journal of Sex, Edited by George Bedborough. London: Office of the Legitimation League, 1897–1899. George Bedborough’s copies.

In the years immediately following the 1895 conviction of Oscar Wilde for “gross indecency” with men, any publication that discussed so-called deviant passions—whether homosexual or heterosexual—risked prosecution. Nevertheless, the radical Legitimation League, which had been dedicated since 1893 to securing legal rights for children born outside of marriage, and which also advocated “free unions,” started a monthly paper in 1897. Under the editorship of George Bedborough, the Adult offered articles on such controversial topics as “Free Love and Lesbian Love” (January 1898) and included “A Note on ‘The Woman Who Did’” by the novel’s author, Grant Allen (March 1898). In May 1898, Bedborough was arrested for selling a copy of Sexual Inversion by Havelock Ellis (1859–1939) to an undercover detective, and the Adult ended its run soon after. The pages open here of Bedborough’s own copy of the magazine show a few of the personal ads sent by readers in search of free unions, along with a portrait of the American-born Lillian Harman (1869–1929), who was Honorary President of the Legitimation League.

Henry James, 1843–1916. The Awkward Age. London: William Heinemann, 1899. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed “To Jonathan Sturges, to bribe him to come back, Henry James,” with non-authorial inscription “From the Author.”

Many scholars have peered into the submerged homoerotic passions that underlay both Henry James’s fiction and his life. Among his close companions in the 1890s was the American-born Jonathan Sturges (1864–1909) who, despite a severe physical disability, traveled to London and moved in the gay circles that surrounded Oscar Wilde. Indeed, following Wilde’s conviction and imprisonment on the charge of “gross indecency,” Sturges reportedly tried—though in vain—to persuade James to sign an 1896 petition requesting a pardon for Wilde. Sturges stayed often with James at Lamb House and did so for weeks and even months at a time, including the period when James was writing The Awkward Age. Some critics have speculated that the conclusion to that novel, in which the avuncular Mr. Longdon invites vulnerable young Nanda to his country house, reflected James’s own protective feelings toward Sturges, to whom he has inscribed this copy of the book as a “bribe” to make him return.