Photography was, especially for many well-to-do Victorians, a delightful hobby. But for Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a lecturer in mathematics at Christ Church, Oxford—famous now under his pen name, “Lewis Carroll”—it was a passion. In recent years, there have been scandalous revelations about his penchant for photographing young girls. Less well known is the eager interest he took in photographing friends and acquaintances from the world of the arts, including the Pre-Raphaelites. Displayed here is a very rare image: the sole depiction of all four adult Rossetti children (Christina; Dante Gabriel; William Michael; Maria)—each of whom was a writer, while Dante Gabriel was also a painter—with their mother Frances Polidori Rossetti (1800–1886), the figure in the center, posed in the garden at 16 Cheyne Walk. The only other known print of this image is owned by the National Portrait Gallery in London.

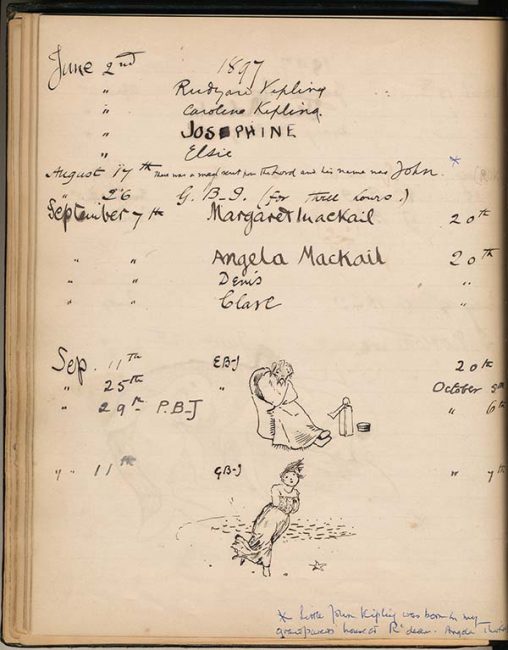

William Allingham, 1824–1889, and Helen Paterson Allingham, 1848–1926. The Book of Sonny, autograph manuscript, 1875–ca. 1907.

Was there a more sociable couple or a more passionately doting set of parents in Victorian England than the Allinghams? Two years after their first child (Gerald, known familiarly as “Sonny”) was born in 1875, they began keeping this record of his tastes, toys, activities, and interactions with their wide circle of famous friends. These included Tennyson, Carlyle, Robert Browning, and George Eliot. Each parent was able to turn what might otherwise have been an ephemeral family document into a work of domestic art. The Irish-born William Allingham was a well-regarded poet, and the diary that recorded his own illuminating encounters with literary contemporaries appeared in print after his death. Helen Paterson Allingham, who was a gifted watercolorist and a commercially successful illustrator (her commissions included the 1874 magazine serialization of Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd), provided the sketches that sweetly punctuated these accounts of childhood adventures. But their beloved Sonny never grew up to be the prominent public figure that the Allinghams envisioned.

The Garland of Rachel, by John Addington Symonds and Divers Kindly Hands. Oxford: Printed at the Private Press of H. Daniel, 1881. Presentation copy from Emily Daniel to Dr. Horatio Percy Symonds.

Many Victorian parents were passionately devoted to their young children. Few expected their friends to demonstrate fervent appreciation of a one-year-old equal to their own and, moreover, to express it in verse, as did (Charles) Henry Daniel (1836–1919) and his wife, Emily. Together, Henry and Emily, who ran the Daniel Press, a private press that specialized in fine printing, produced thirty-six copies of this little volume, which celebrated their daughter Rachel. Among the many distinguished literary figures who were persuaded to offer tributes to the Daniels’ infant were (Henry) Austin Dobson (1840–1921); Andrew Lang (1844–1912); “Lewis Carroll” (1832–1898); W. E. Henley (1849–1903) and John Addington Symonds (1840–1893), whose own passions were Classical literature and the study of “inversion” (homosexuality). This copy, which was accompanied by Henry Daniel’s Preface to the Garland, was sent by Emily Daniel as a wedding present to Horatio Percy Symonds (1850–1921), John Addington Symonds's cousin.

Until Mark Samuels Lasner acquired it and shared the exciting news of its contents with scholars in 2004, this visitors’ book was almost wholly unknown. It had been for decades the property of Angela Thirkell (1890–1961), the comic novelist and granddaughter of Sir Edward Burne-Jones and his wife, Georgiana (1840–1920). Kept by Burne-Jones to record the visits of family members and friends to his house in Sussex, it is quite literally a treasure trove. Not only does it contain the signatures of famous guests, such as William Morris, but Burne-Jones’s comic sketches and caricatures of them. Here, it is open to show the signature of Gerald Duckworth (1870–1937), the publisher, who was the half-brother of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, and also caricatures of both Edward and Georgiana Burne-Jones. More significant, though, is the event mentioned on the left-hand page: the birth on 17 August 1897 of Rudyard and Carrie Kipling’s son John. That happy moment seems overhung, in retrospect, with tragedy. “Jack” Kipling would (at his father’s insistence) grow up to be a soldier in the First World War. He was reported missing in action at the Battle of Loos, but his body was never found. Devastated by this loss, Rudyard Kipling wrote the poem “My Boy Jack” (1916).

J. M. (James Matthew) Barrie, 1850–1937. The Little White Bird. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1902. Author's presentation copy to his sister, Margaret Barrie, inscribed "Maggie from J.M.B.”

Some Victorian writers developed passions for men, some for women, and some for children, but J. M. Barrie fell in love with an entire family: Arthur and Sylvia Llewelyn Davies and their five sons. First encountering the latter in the late 1890s, while walking his dog in Kensington Gardens, he made these small boys his regular playmates, and they became his obsession. Even as The Admirable Crichton, his satirical play for adults about the British class system, was on the West End stage in 1902, Barrie’s thoughts were elsewhere: on the fantasy, inspired by the Llewelyn Davies children, that emerged halfway through The Little White Bird, about a mercurial spirit named Peter Pan who could fly. That section would later be published separately as Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens (1906), but only after it engendered a theatrical work, Peter Pan or the Boy Who Would Not Grow Up (1904), so staggeringly successful that it defined forever how plays for or about children would be written and performed. This copy of The Little White Bird was presented to his sister, Margaret, in whose home (according to her housekeeper) Barrie saw a moving light that was the genesis for the stage effect of Tinkerbell’s appearance.