Lewis Carroll, 1832–1898. Le avventure d’Alice nel paese della meraviglie, tradotte dall’inglese da T. Pietrocòla-Rossetti; con 42 vignette di Giovanni Tenniel. Londra: Macmillan and Co. 1872. Translator’s presentation copy, inscribed “Alla cara e affettuosa mia Cugina Christina G. Rossetti il Traduttore.”

If ever there was a Victorian work that needs no introduction, it is Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), the fantasy inspired by “Lewis Carroll’s”—that is, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson’s—passion for young Alice Liddell (1852–1934). This version of it, however, might require an introduzione. Displayed here is its translation into Italian by T. (Teodorico) Pietrocola-Rossetti (1825–1883), a first cousin of the poet Christina Rossetti (1830–1894), to whom he has inscribed this copy. She had also received a copy of the first edition in 1865 from Dodgson himself and had found the story delightful.

Kate Greenaway, 1846–1901. A Day in a Child’s Life: Illustrated by Kate Greenaway; Music by Myles B. Foster ... ; Engraved and Printed by Edmund Evans. London: George Routledge and Sons, [1881]. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed “J. Ruskin Esqre. from Kate Greenaway Dec. 1881.”

Kate Greenaway’s most rewarding passion was for Aesthetic art and design, which she shared with the magisterial critic, John Ruskin (1819–1900); her least rewarding was for Ruskin himself. Although they both loved children and believed that tutelage in Beauty (capital “B”) should begin early through illustrated books, as well as through the wearing of Regency-style dress, Ruskin’s adoration of young girls had a more sinister side and precluded erotic interest in adult women like Greenaway. He was, however, more than happy to act as a mentor and encourage her to grovel before him, awaiting his approval of her artistic efforts. To the gift of this copy of a collection of songs decorated throughout with her pictures, he responded enthusiastically, placing her work in the exalted company of that of Edward Burne-Jones.

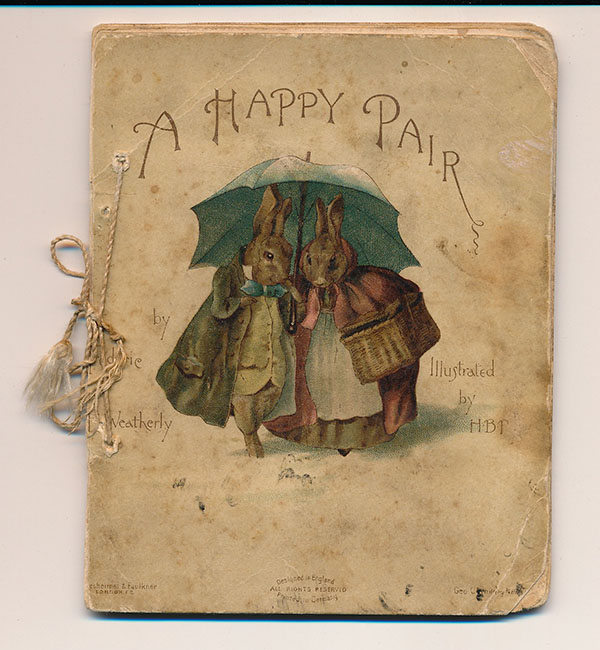

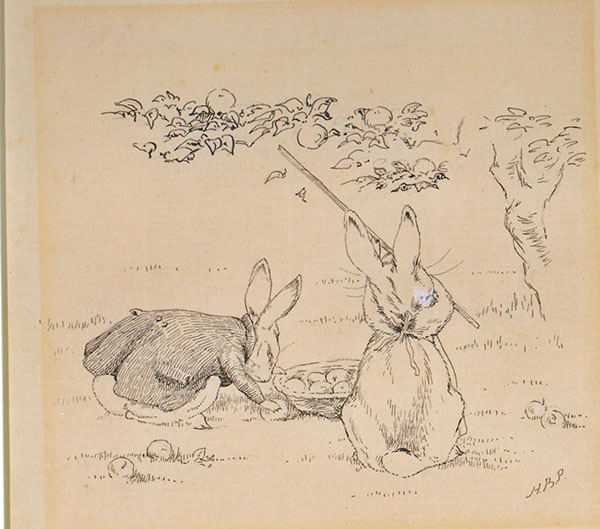

The “H.B.P.” who supplied six images for Frederic Weatherly’s poems was none other than (Helen) Beatrix Potter (1866–1943). This tiny object was her first illustrated book and represented early, if limited, success in her campaign to earn a living as a professional artist. She would, of course, hit the jackpot in the following decade with The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902) for Frederick Warne & Co. Her own wish to be part of a “happy pair” was frustrated by her status-conscious parents, who objected to her passion for the publisher Norman Warne (1868–1905) and kept them from marrying, on the grounds that his was not a profession but a mere trade.

Although she was a close observer of nature, Beatrix Potter was also a fantasist. Her portraits of animals were detailed and precise, and often based on careful study of the pets she kept around her (including her bunnies, “Benjamin Bouncer” and “Peter Piper”); yet the rabbits she drew wore clothes and engaged in activities such as apple-picking that no one else ever saw them perform. Much as she loved the world of art—Sir John Everett Millais (1829–1896), the Pre-Raphaelite painter, was a family friend—she loved even more its practical application through scientific illustration and had hoped to make that her career, before turning to writing and illustrating books for children. Potter’s abiding passion, however, was for the preservation of the English countryside. In later years she dedicated herself to farming in the Lake District, though there is no evidence that she successfully employed rabbits to harvest any crops for her.

William Ernest Henley, 1849–1903. Lyra Heroica: A Book of Verse for Boys, Selected and Arranged by William Ernest Henley. London: Published by David Nutt, in the Strand, 1892. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed to Robert Louis Stevenson, “Author's copy No. 92 W. E. Henley Mother and Son With the author’s compliments & thanks 4th December 1891.”

United by their respective experiences with lifelong ill health, as well as by their shared literary ideals, W. E. Henley, the English poet and magazine editor, and Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894), the Scottish poet and novelist, enjoyed many years of close friendship. Their relationship came to an abrupt halt, however, in 1888. The stumbling block was Stevenson’s passionate anger on behalf of his wife, Frances (“Fanny”) Van de Grift Osborne (1840–1914), after Henley suggested that she had published a short story under her name, but not written it herself. Although they never achieved the same intimacy again, Stevenson and Henley did manage to repair their relations to some degree, as this presentation copy of Lyra Heroica shows. When compiling his anthology of poetry intended for a readership of boys, Henley included one poem by Stevenson—“Mother and Son”—as mentioned in the inscription, and it appears to have served successfully as an olive branch.