Olive Schreiner, 1855–1920. The Story of an African Farm: A Novel, by Ralph Iron. London: Chapman and Hall, Limited, 1883. With autograph letter to Frederic Chapman, [July 1888].

Encountering this narrative set in the South African Karoo, readers were shocked, but also titillated, by the passions of the fictional characters and by their ways of expressing (and acting on) them. The novel by the pseudonymous “Ralph Iron” became a bestseller in Britain and inaugurated the “New Woman” movement in literature, ten years before that term existed to describe it. Lyndall, Olive Schreiner’s female protagonist, refuses to fit the mold either of a simpering girl or a respectable lady. She rails against the so-called chivalry of men who demean and sexually exploit women, while restricting their access to education and political rights. All too soon, she dies while pregnant out of wedlock, but not before one of the men who loves her has cross-dressed and come to her deathbed in the guise of a female nurse. That the august firm of Chapman and Hall would have issued such a work was surprising, but explained by the enthusiasm of the publisher’s reader—none other than the poet and novelist George Meredith (1828–1909). With this copy of The Story of an African Farm is a letter from Schreiner to her publisher, Frederic Chapman (1823–1895), from 1888. By then, she was living in England and, while noting that sales of her novel had diminished, claimed to care more that it still was circulating widely.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1859–1930. The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London: George Newnes, 1893. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed “H. Greenhough Smith with A Conan Doyle’s cordial greetings May 15/93”: inserted is Doyle’s calling card.

What would Sherlock Holmes have done with the calling card of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle? Would he have sniffed it for traces of smoke and then identified the brand of tobacco? And what would he have made of the inscription in this volume of Holmes stories, presented to H. (Herbert) Greenough Smith (1855–1935), editor of the Strand magazine in which they had first appeared? Would he have deduced from its tone that the author was grateful for the acclaim that publication in the Strand had been bringing him since 1891? Or would Holmes also have suspected, from the less-than-effusive “cordial greetings,” that Doyle was restive and eager to move on, and that he already planned to kill off his detective hero in the December 1893 issue? By May 1893, readers were more passionately eager than ever for new narratives about Holmes. His creator, however, felt increasingly harassed by such demands.

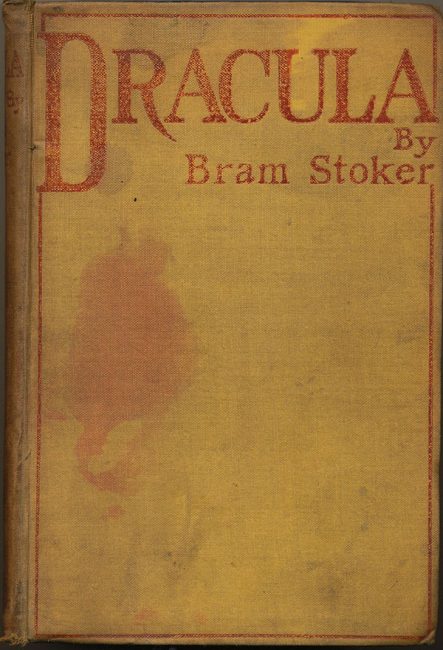

The year 1897 was a busy one for bloodsuckers, at least in London. It saw the display, at the summer exhibition of the New Gallery, of the painting The Vampire by Philip Burne-Jones (1861–1926), son of Sir Edward and Georgiana Burne-Jones. His Decadent image of a half-dressed woman, who appears to have sated her unholy passions on the limp body of the man lying under her with an open wound on his chest, startled viewers. It also reputedly inspired Rudyard Kipling to write his poem, “The Vampire,” which invited (male) readers to identify with the luckless “fool” who wasted his love on a (female) “rag and a bone and a hank of hair.” The model for the predatory woman in the painting was said to be the artist’s adulterous lover, the renowned West End stage star, Stella Patrick Campbell (1865–1940). This copy of Bram Stoker’s immortal novel about the undead—which, by coincidence, appeared almost simultaneously with these two other vampire-themed works—was presented to her by its author.

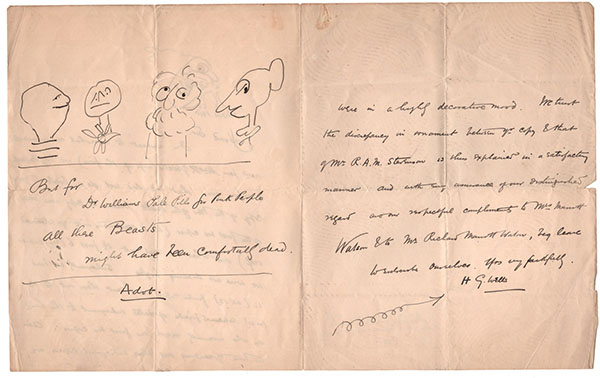

H. G. Wells inscribed this copy of The War of the Worlds “with reverence” to R. A. M. Stevenson, the Scottish art critic and Professor of Fine Arts at University College, Liverpool (now the University of Liverpool), who was also the cousin of the late Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894). Reverence, however, was not a quality that Wells possessed in abundance. As the letter also displayed here—to H. B. (Henry Brereton) Marriott-Watson (1863–1921), a journalist and writer of fiction—demonstrates, he was much more in his element when being silly. As well as sending polite and sincere greetings to Marriott-Watson and his romantic partner, who wrote poetry under the pen-name “Graham R. Tomson” and called herself Rosamund Marriott-Watson (1860–1911), Wells indulged his comic side. He had a passion for doodling. In this case, he drew a group of ridiculously deformed heads and declared that they were an advertisement for a non-existent patent medicine: “But for Dr Williams Pale Pills for Pink People all these Beasts might have been comfortably dead.”

That Mary Annette Beauchamp (1866–1941) is, in this photograph, clutching flowers seems only appropriate, for they were her passion. She shared her obsession with thousands of readers through her tremendously popular pseudonymous work, Elizabeth and Her German Garden (1898). So successful was it, that she became known in her private life, too, as “Elizabeth.” The story of the German garden reflected her domestic happiness, as well as some of the tensions, at Nassenheide, the estate of the Count von Arnim, whom she married in 1891. In later years, she became estranged from him and, after 1907, briefly took up with H. G. Wells. Although married, Wells was always more than willing to sleep with good-looking, intelligent women and to demonstrate that, after Socialism, his deepest commitment was to the philosophy of Free Love.

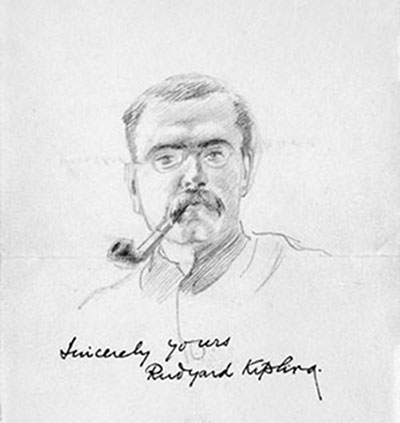

Rudyard Kipling was, of course, the great apologist for British Imperialism. His passion for Empire enabled him to recast as a poetic enterprise what to many was a cruel exercise in racism, domination, and greed. Never a mere propagandist, he was also an artist in words and, surprisingly, even in visual media. With Sir Edward Burne-Jones, the Pre-Raphaelite painter, as his uncle, a talent for drawing was something he took for granted. In this letter to an American acquaintance, the writer Helen Bartlett Bridgman (1855–1935), he apologizes for having no photograph to send in return for one from her and encloses instead this accomplished self-portrait sketch. Bridgman, who met Kipling on her first visit to England while he was still in his twenties, would later devote a chapter of her memoir Within My Horizon (1920) to describing his endearing “sensitiveness” and quality of seeming “something of the child” at a time when he was “new to London, [and] somewhat homesick for the warmth of India.”

![Autograph letter to Helen Bartlett Bridgman, 24 June [1890] Autograph letter to Helen Bartlett Bridgman, 24 June [1890]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/victorian-passions/wp-content/uploads/sites/69/2019/12/Autograph-letter-to-Helen-Bartlett-Bridgman-24-June-1890.jpg)