Walter Pater, 1839–1895. Studies in the History of the Renaissance, London: Macmillan and Co., 1873. Henry James’s copy.

This was the book that launched a thousand Aesthetes—many more than that, in fact. Through its “Conclusion,” in particular, Walter Pater encouraged an entire generation to “catch at any exquisite passion,” to burn with a “hard, gem-like flame,” and to appreciate Art for Art’s sake. So nervous did the art critic and Oxford tutor become on witnessing the response to it, however, that he removed this controversial section of Studies for the publication of the second edition. The copy of the book shown here belonged to Henry James (1843–1916). His later creation of fictional characters ranging from Gilbert Osmond in The Portrait of a Lady (1881) to Mrs. Gereth in The Spoils of Poynton (1897) owed much to his reading of Pater’s Aesthetic polemic.

Before he achieved literary fame in 1894 as the author of Trilby, and thus as creator of the immortal character of Svengali, George Du Maurier (often known as “du Maurier”) had a thriving career at Punch. In his position as a staff artist, he produced cartoons weekly for many years, using the magazine as a platform for humorous social commentary through both drawings and captions. Among his favorite targets was Oscar Wilde, whom he caricatured repeatedly as “Maudle”—an allusion to Wilde having burst on the London cultural scene after graduating from Oxford’s Magdalen (pronounced “Maudlen”) College. Although Du Maurier was a Dandy and a bohemian himself, he remained a passionate deflater of what he saw as the pretensions of Wilde’s Aesthetic band.

Charles S. Ricketts, 1866–1931. The Moon Horn’d Io, ink on prepared paper, [1893].

The passions of the speaker in Oscar Wilde’s long poem The Sphinx (1894) were red-hot, as he mused about a fantastic creature, “half woman and half animal,” and about her lurid erotic life in the ancient world. Charles Ricketts’s designs for the gorgeously illustrated volume issued by Elkin Mathews and John Lane’s Bodley Head press were, on the other hand, often restrained and almost abstract. The drawing shown here is for the image that accompanied the poem’s lines about the myth of Io, who was turned into a white heifer by her lover, the god Zeus. For Ricketts, as for Aubrey Beardsley and other artists of the Decadent 1890s, Classical Greece provided a welcome excuse to draw naked bodies—especially, androgynous ones—and to explore taboo subjects.

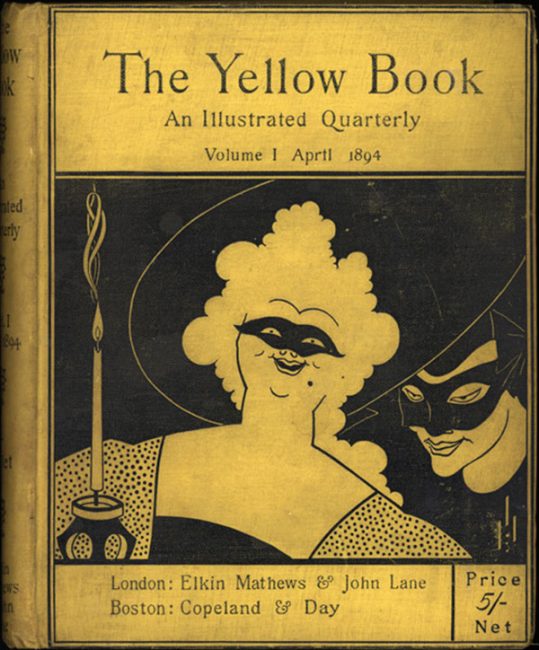

The Yellow Book was greeted with passionate cries of outrage on its April 1894 launch. More than anything, it was the art—and especially the work of Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898)—in the first issue that shaped the hostile critical reception and branded the new quarterly as the mouthpiece of the Decadents. From the lurid color of its cloth binding to the leering, unwholesome faces on its front cover, daring the viewer to pluck it from the respectable shelves of W. H. Smith’s shops in railway stations, the Yellow Book was like no other British periodical. Richard Le Gallienne (1866–1947)—friend to the publisher John Lane and publlsher’s reader for the Bodley Head firm—was an important contributor from the outset, though he was less a Decadent than an Aesthete in the mold of Oscar Wilde during his longhaired, soulful “Bunthorne” days. The copy shown here of the first number belonged to Le Gallienne, whose poem “Tree-Worship” appears in it.

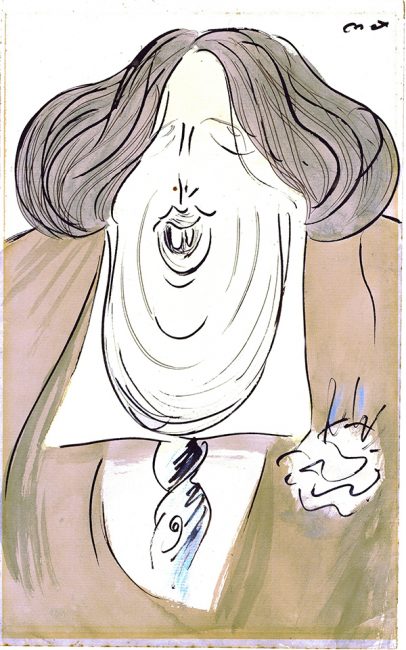

While he had great respect for Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) as a writer and wit before the catastrophic Spring of 1895, and while he felt nothing but sympathy after Wilde’s arrest, conviction, and imprisonment for so-called “gross indecency” with men, Max Beerbohm was, nonetheless, filled with horror by what he viewed as Wilde’s excesses. These involved, throughout the early 1890s, not merely an increasingly overt sexuality, but a self-indulgent sensuality: a readiness to eat too much, to drink far too much, and to live—as Lady Bracknell put it in Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1895)—entirely for pleasure. To Beerbohm, who adhered strictly to the Dandy’s code of restraint and renunciation, such intemperate passions were anathema. They offended him on artistic grounds, and he took out his feelings when drawing Wilde’s face. In this caricature, which Beerbohm presented to his dear friend, the author (and fellow Wilde admirer) Reginald Turner (1869–1938), Wilde’s perceived dissolution is rendered literal. He sinks into his multiple chins, and his mouth swells into an obscene orifice.

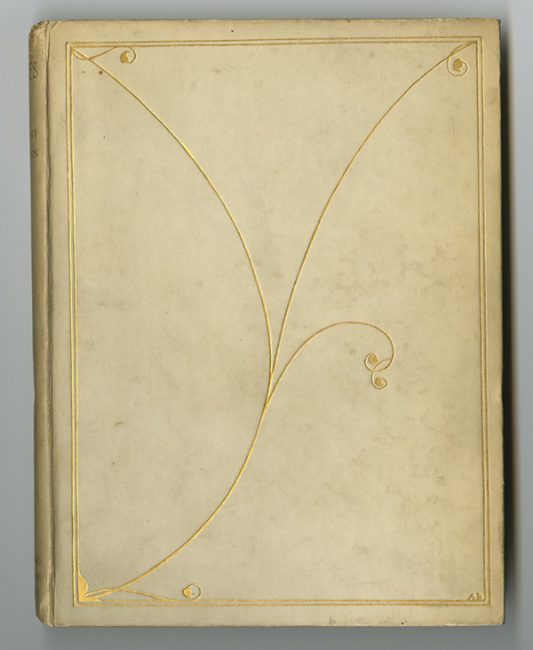

Having made his living as a dealer in pornography, Leonard Smithers (1861–1907) knew all about the private and sometimes unsavory passions of his Victorian contemporaries. Among his passions, however, was one for avant-garde art, whether literary or visual. He satisfied that by becoming a publisher—not only of the short-lived but influential magazine, the Savoy (1896), but of books by Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, Ernest Dowson, and others. Without him, there might well have been no British Decadent movement in prose, poetry, or illustration, especially after the Wilde Trials of 1895, when less courageous publishing firms fled from anything controversial. This copy of Verses, with its spare and abstract cover design by Beardsley, was inscribed warmly by Dowson to Smithers and sent from Pont-Aven, France.

Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev, 1818–1883. A Lear of the Steppes and Other Stories: Translated from the Russian by Constance Garnett. London: William Heinemann, 1898. Henry James’s copy.

As well as being friends with Ivan Turgenev, Henry James (1843–1916) was an admirer of the Russian author’s melancholy fiction. He published an appreciative review of the 1874 German translation of “A Lear of the Steppes” (a.k.a. “A King Lear of the Steppes”). In 1898, Constance Garnett (1861–1946) issued an English translation of it. James owned this copy, and on the back flyleaf sketched out chapter divisions for the novel he was engaged in composing: The Awkward Age, his tale of a young girl who maintains her innocence, despite being encircled by the corrupt passions of adults. The critic and collector Adeline Tintner Janowitz (1912–2003), who owned this copy before Mark Samuels Lasner acquired it, was the first to recognize its scholarly importance. She is remembered fondly for her breadth of knowledge about James and for her avant-garde fashion sense, as a wearer of leather mini-skirts when she was in her seventies.