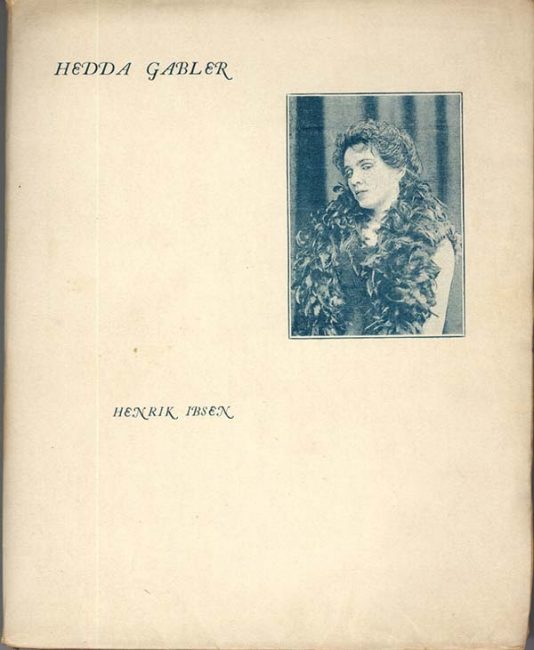

Late-nineteenth-century Britain saw the rise of cults for Zola’s fiction and Wagner’s operas, but no group was more passionate about importing new Continental art than the Ibsenites. Leading the efforts to revolutionalize English theatre by staging Ibsen’s dramas were critics such as Edmund Gosse (1849–1928) and William Archer (1856–1927), as well as performers such as Marion Lea (1864–1924) and especially Elizabeth Robins (1862–1952). The American-born Robins—who was also a playwright, a novelist, and later a women’s suffrage supporter—was the force behind the first London production in 1891of Hedda Gabler, in which she starred and which she also helped to translate. Ibsen’s account of a restless woman who finds no outlet for her energies in domesticity, and who chooses suicide over control by a man wishing to blackmail her, was the perfect vehicle for Robins, whose own life was filled with scandal and unconventional relationships. This copy of Hedda Gabler with photographs from the first production belonged to Robins herself and is accompanied by her letter to the British playwright T. Malcolm Watson.

Bernard Shaw, 1856–1950. Mrs. Warren’s Profession: A Play in Four Acts. London: Grant Richards, 1902. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed “To Max Beerbohm from G. Bernard Shaw. 10th June 1902.”

Sir Max Beerbohm, 1872–1956. George Bernard Shaw, ink and wash on paper, 1909.

What so shocked contemporary sensibilities about Mrs. Warren’s Profession was its central character’s lack of passion. The Victorians were used to literary representations of so-called “fallen women” as sad creatures, who had foolishly succumbed to ungoverned desires. G. B. Shaw’s Mrs. Warren was instead a cool-headed ex-prostitute and current brothel owner for whom sex-for-money was strictly business, and a business she was proud of managing well. An ardent Socialist, Shaw indicted the capitalist system at every level for having turned British society into a giant whorehouse, with a madam as its true queen. As a result, this drama, although written in 1893, did not receive its first performance until 1902, through the members-only Stage Society. The Irish-born Shaw’s fierce jabbing at English audiences, as with a pitchfork, was frankly devilish, as this caricature by Max Beerbohm suggested. Plus, in 1897 Shaw had written a play about the American Revolution titled The Devil’s Disciple, cementing for Beerbohm the satanic connection. The copy of Mrs Warren’s Profession shown here was presented by Shaw to Max Beerbohm.

Sir Max Beerbohm, 1872–1956. Max Beerbohm’s walking stick, ebony, ivory handle with silver band, [ca. late 1890s].

As drama critic for the Saturday Review from 1898 to 1910, Max Beerbohm had a professional excuse to indulge his love of the theatre. The stage was a passion, too, of the translator Alexander Teixeira de Mattos (1865–1921), who in the 1890s worked for fellow Dutchman J. T. Grein (1862–1935) at the Independent Theatre Society, which produced plays by Henrik Ibsen, G. B. Shaw, and “Michael Field” (Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper). But more than anything, Beerbohm loved an inside joke. He presented to Teixeira de Mattos—who married the widow of Oscar Wilde’s brother, William, in 1900—this walking stick, the bulbous head of which was carved to look like Beerbohm’s caricature of his friend’s head. After Teixeira de Mattos’s death, the stick was returned to him. Beerbohm’s widow later gave it to the publisher Sir Rupert Hart-Davis (1907–1999), who edited Beerbohm’s letters. Hart-Davis, in turn, gave it in 1987 to Mark Samuels Lasner.

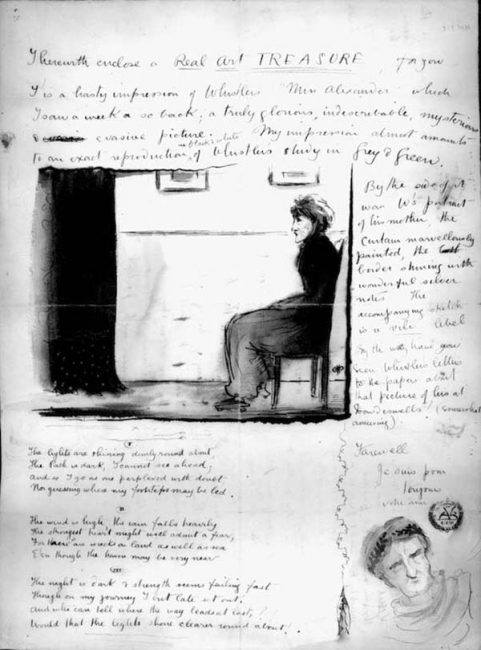

G. F. (George Frederick) Scotson-Clark (1872–1927)—an artist who in 1899 would produce The “Halls,” his volume of images of music hall stars—loved the theatre. So, too, did his school friend Aubrey Beardsley. In later years, Beardsley would draw actresses. His Portrait of Mrs. Patrick Campbell appeared in the first issue of the Yellow Book in April 1894, and his famous illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s Salome (1894) were, of course, also images of a performer—a dancer. But in this tour de force from 1891, Beardsley stages a kind of one-man show with his own face. His letter includes multiple self-portraits, and in one he substitutes himself for the figure of the mother in J. M. Whistler’s celebrated Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1 (1871). Commenting on Whistler’s work, Beardsley singled out for praise the curtain as “marvellously [sic] painted, the border shining with wonderful silver notes.” Beardsley often was, so to speak, drawn to curtains. They turned up frequently in his work as signifiers of theatricality, even when no one was actually onstage.

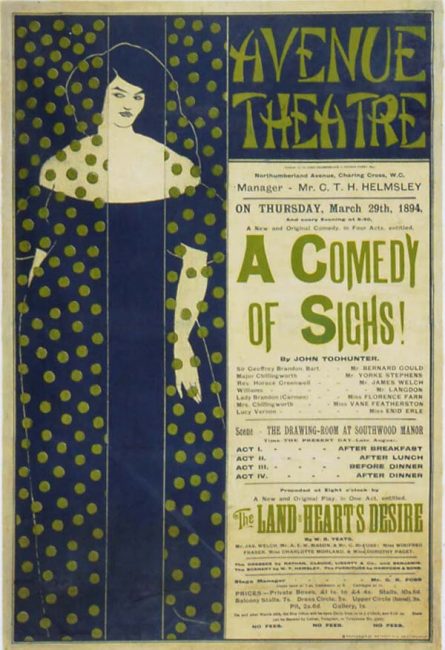

This is one of only a few surviving examples of the poster that Aubrey Beardsley designed for a theatrical double bill, commissioned to do so by the author and actress Florence Farr (1860–1917). Farr’s passion for the stage was something she shared with her friend Annie Horniman (1860–1937), who took up management of the Avenue Theatre and engaged playwrights to create new work for it. Today, audiences might expect the order of these advertised plays to be reversed. The one-act fantasy is famous now as the first play by William Butler Yeats (1865–1939) to be performed in public; the drawing-room comedy by John Todhunter (1839–1916) has sunk into oblivion. Beardsley’s image appears to allude to the role performed by Farr in Todhunter’s four-acter—a character named “Carmen,” described by the critic for the Speaker (7 April 1894) as “an exotic, out of her element in a commonplace English household” and likened to the “now notorious lady in the first story of Keynotes” (the 1893 New Woman-ish volume by “George Egerton” for which Beardsley had designed the covers and title page).

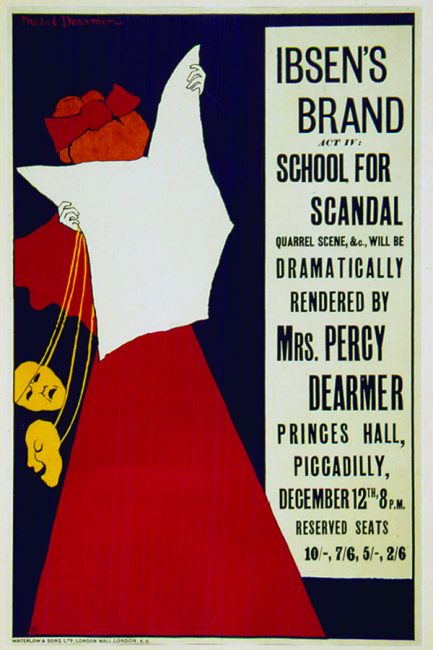

The passion for just causes that animated Mabel Dearmer’s life also led to her premature death. In the midst of the First World War, she succumbed to typhoid while doing volunteer work with a women’s medical unit at the battlefront in Serbia. With that, the London theatre world lost an important and versatile figure. She was a playwright, specializing in works for young audiences and in new versions of the Christian Mystery plays. (Her husband, the writer Percy Dearmer [1867–1936] was an Anglican priest.) As this 1895 poster for her one-woman show records, she was also an artist and a seasoned stage performer, and she would later put her many talents to use in supporting Socialism and women’s suffrage.

William Nicholson, 1872–1949. Souvenir Scroll for the Ellen Terry Commemoration Banquet, color lithograph, [1906].

The preservation of this fragile memento was due entirely to the passionate fandom of the actress May Ward (1888–1958), who adored her friend, Dame Ellen Terry (1847–1928). Terry, whose wildly successful theatrical career began when she was a child, celebrated her fiftieth year on the British stage in 1906. Like the reigning figure she was, Terry was fêted with a gala event at the Drury Lane Theatre Royal to commemorate her “Golden Jubilee.” Guests at the 12 June celebration, which included performances and a grand banquet, received this beautiful but rather unwieldy scroll, designed by the artist William Nicholson (who had depicted that “other” queen, Victoria, much less flatteringly as a boneless black blob, in an 1897 woodcut for the New Review). Carefully spreading the paper, they could see Terry in all her most famous roles and appreciate a woman who was continually embraced by the public, despite her non-conformity to the rules of Victorian morality.