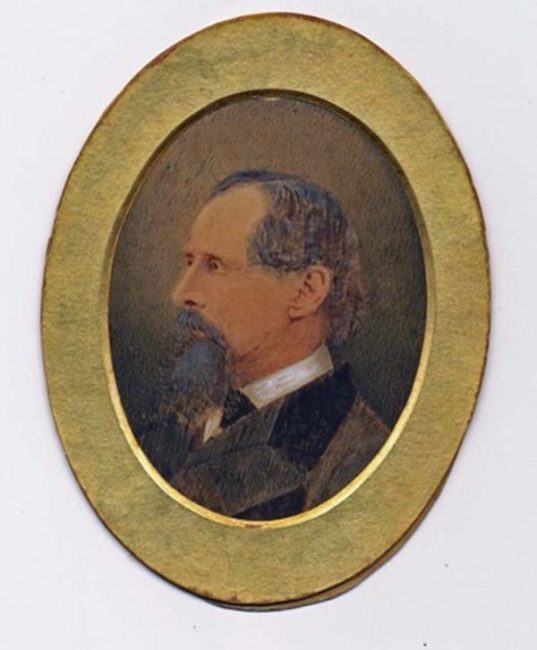

John Forster, 1821–1876. The Life of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872–1874. Anthony Trollope’s copy.

Their passions for writing—and for making money in the process—were equally strong, but in temperament, methods, and public personae, Dickens and Trollope could not have been more different. Charles Dickens (1812–1870) was a hurricane-like force blowing through the Victorian world, sweeping along thousands of readers with his serialized fiction, while attempting to sweep away social ills such as child labor. (This posthumously published biography by his friend John Forster would reveal the lifelong psychological damage caused by Dickens’s own boyhood employment in a factory.) The youth of Anthony Trollope (1815–1882) too, had been traumatic; he compensated by leading a disciplined and orderly life as an adult, balancing the composition of novels with a civil service position in the Post Office. In The Warden (1855), the first of the “Barsetshire” novels, Trollope unleashed his talents as a parodist with a wicked imitation of Dickens’s exhortative literary voice. He was on record as finding Forster’s biography “distasteful” for revelations about Dickens’s youth and personal relationships. Reading it helped determine Trollope to be more cautious in producing his own Autobiography (1883).

By 1858, Charles Dickens’s discontent with domestic life and his adulterous passion for a much younger actress, Ellen Ternan (1839–1914), had divided him from his wife Catherine Hogarth Dickens (1815–1879) and split apart their family of nine children. Their adolescent daughter Catherine (known both as “Kate” and “Katey”), who had always been her father’s favorite, went to live with him. Their relationship was sometimes turbulent, but her respect for him as Victorian Britain’s most celebrated novelist shows in this portrait. Her own passion was for art, especially for painting. It endured through her passionless marriage to the artist Charles Collins (1828–1873)—brother of the novelist Wilkie Collins, her father’s close friend—and, after her husband’s death, through her marriage to another artist, the Italian-born Carlo Perugini (1839–1918).

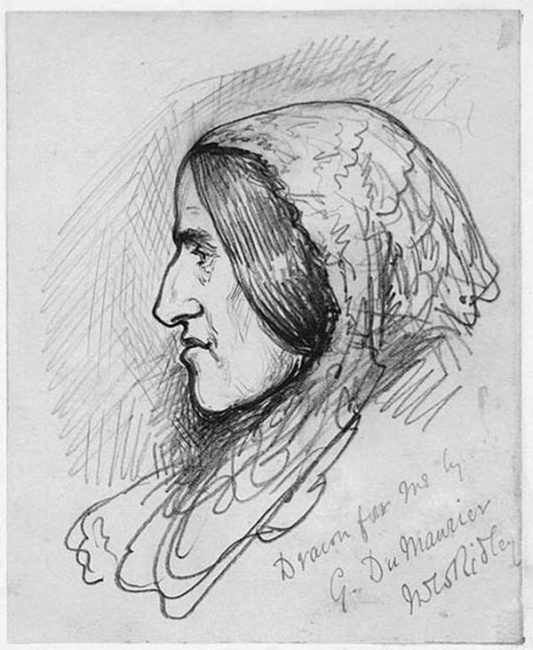

By the late 1870s, there was no question that “George Eliot,” the pen name of Mary Ann Evans (1819–1880), was the object of public acclaim. In private, however, she remained a polarizing force, especially in literary circles. While she had long inspired passionate devotion in women friends and in a number of men—including, of course, her romantic partner George Henry Lewes (1817–1878) and, after Lewes’s death, the much younger John Cross (1840–1924), to whom she was briefly married—she proved off-putting for some male writers and artists, especially those of the up-and-coming generation. For them, her appearance, which was not traditionally feminine or delicate, combined with her gravity, sagacity, and insistence upon weighing all matters in ethical terms, made her less than appealing. To George Du Maurier, for instance, she seemed an almost gargoyle-like figure. In this unflattering sketch probably done from life, the cartoonist for Punch and future author of Trilby (1894), who valued the lightness and wit of the Parisian vie de bohème, demonstrated in visual terms how inimical to his own tastes he found her.

George Gissing, 1857–1903. New Grub Street: A Novel. London: Smith, Elder, 1891. Advance copy sent to Frederick Dolman: with autograph letter to Dolman, 2 April 1891.

Passion for a wife who does not share his values proves the undoing of Edwin Reardon, protagonist of this notoriously grim novel about the literary marketplace of the 1880s. The plot reflected George Gissing’s own sad circumstances, as not once but twice he married women who viewed with incomprehension his dedication to intellectual and artistic pursuits and refusal to write what might be popular and profitable. To Gissing, as well as to the idealistic and thus poverty-stricken authors who inhabit his fictional modern Grub Street in London, the periodical press was a particular bête noire, responsible for corrupting the tastes of the British public. It is no surprise that, in the letter shown here, Gissing turned down a request from the journalist Frederick Dolman to be interviewed for the Pall Mall Gazette, insisting that his novel (which Dolman received in this unique trial binding in red cloth) would have to speak for itself as “a work of art,” and that he had “nothing of interest” to say to the magazine’s audience.

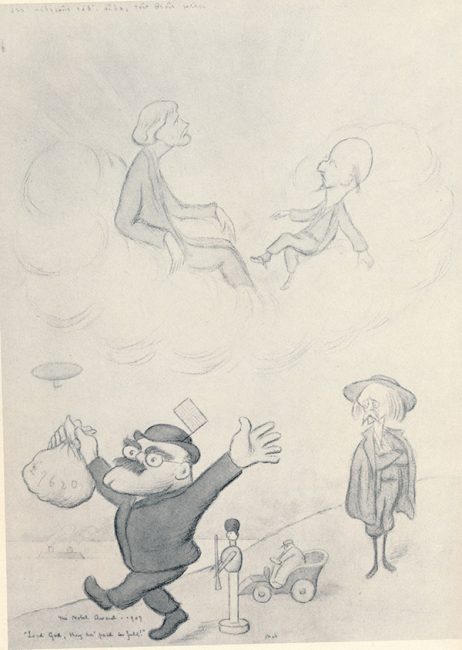

While acknowledging Rudyard Kipling’s power as a writer, Max Beerbohm deplored the use to which he put his talents as the mouthpiece for British Imperialism. The assumed coarseness and affected Cockney slang, the bluster and militarism, the sentimental jingoism—all offended Beerbohm to the core. In Kipling’s hyper-masculine posturing, too, Beerbohm sensed overcompensation for his being short of stature; thus Beerbohm loved to draw him as smaller-than-life. That a man of such ignoble passions would be awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize in Literature was the last straw. In this caricature, Algernon Swinburne (1837–1909) and George Meredith (1828–1909)—both of whom Beerbohm considered more deserving of the award—occupy the Empyrean heights, and (Thomas) Hall Caine (1837–1909) gazes balefully on Earth, as Kipling struts away with his swag. This drawing was owned by the critic Edmund Gosse (1849–1928), who was a friend of all the men depicted and of the artist, as well.

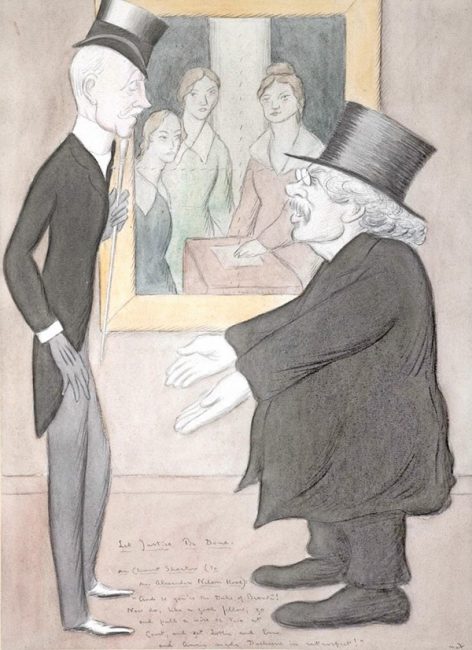

Max Beerbohm’s impulse to caricature rarely extended to women subjects; he exercised his talent for mockery more often at the expense of men. In this case, his target was not actually the physical appearances of the Brontë sisters, to whom he gave lopsided faces balanced on awkwardly drawn bodies, but the famously stiff and amateurish group portrait of Anne, Emily, and Charlotte by their brother. This lampoon of the painting by Branwell Brontë (1817–1848) occupies the background. The foreground is taken up with an imaginary conversation between the journalist Clement K. Shorter (1857–1926) and Alexander Nelson Hood (1814–1904), 1st Viscount Bridport and 4th Duke of Brontë, as Shorter implores the aristocrat to “pull a wire or two at Court, and get Lottie and Em and Annie made Duchesses in retrospect!” Shorter’s passion for the Brontës was well known, and it fueled the writing of multiple studies, such as Charlotte Brontë and Her Sisters; The Brontës and Their Circle; and The Brontës: Life and Letters.

The Four Seasons. [London]: Curwen Press, [1922]. Pocket calendar, used by John Drinkwater as an autograph book.

Although he was born in the nineteenth century, John Drinkwater (1882–1937) was not a Victorian author; his career as a published poet, playwright, and critic began after the death of the Queen in 1901. But his passion for collecting autographs from the many writers whom he met socially meant that his little book of signatures united past and present, as well as figures from both sides of the Atlantic. On these randomly opened pages, we find Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins (1863–1933), author of The Prisoner of Zenda (1894), across from James Joyce (1882–1941), in the year when Ulysses appeared in book form. So, too, the name of Israel Zangwill (1864–1926), the great chronicler of late-Victorian Anglo-Jewish life, sits opposite that of Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951), the equally great chronicler of small-town American life, in 1922, the year of Babbitt. Women writers are also represented, as the presence of the novelist Sheila Kaye-Smith (1887–1956) attests. Elsewhere, Drinkwater has managed to persuade even Virginia Woolf to sign her name in this unprepossessing-looking pocket calendar.