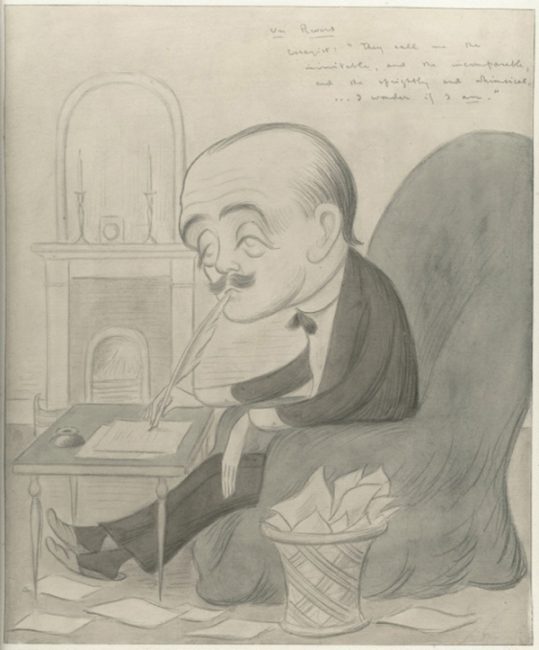

If to love oneself, as Oscar Wilde suggested in An Ideal Husband (1895), was the beginning of a lifelong romance, Max Beerbohm made a career out of nipping such passions in the bud. Admirably, as a master parodist and satirist, he employed both words and images to cast the same cold, deflating regard on himself as on the physical appearances and achievements of others. Un revers was the largest of his self-caricatures. In it, he weighed down his limp body with an unattractively oversized head and balanced quotations from imaginary paeans to his work (“They call me the inimitable, and the incomparable…”) with the discouraging reality of a rubbish basket stuffed with unusable drafts. In his own passionate quest to see Beerbohm treated more seriously, Mark Samuels Lasner for many years planned to issue a bibliography of his writings and art. Intending to reproduce this image as a frontispiece, he paid what was in 1987 the highest price ever recorded for a Beerbohm caricature. Perhaps fittingly, the unfinished bibliography—a revers, a setback or dream that never came to fruition—ended up in the digital equivalent of a rubbish basket, but the wonderful drawing remains.

Sir Max Beerbohm, 1872–1956. Autograph letter to Bohun Lynch, 18 June 1921.

From the time that he began issuing his visual and literary work in the 1890s, Max Beerbohm enjoyed, and has continued to attract, loyal and passionate fans (including, of course, Mark Samuels Lasner). Among his early admirers was a fellow caricaturist and author, John Gilbert Bohun Lynch (1884–1928), who in 1921 wrote to Max Beerbohm at his villa in Italy regarding his plans to publish an assessment of Beerbohm’s career. Beerbohm’s reaction was, metaphorically speaking, to throw up his delicate hands in horror. In this letter to Bohun Lynch, he objected to the very idea of such a critical enterprise: “My gifts are small. I’ve used them very well and discreetly, never straining them; and the result is that I’ve made a charming little reputation. But that reputation is a frail plant. Don’t over-attend to it, gardener Lynch! Don’t drench and deluge it!” So amusing—and important—did Bohun Lynch consider this response that he published it, with Beerbohm’s permission, in the preface to his Max Beerbohm in Perspective (1922).

Gentleman though he was, Max Beerbohm overcame his customary aversion to ridiculing women’s bodies and made an exception for Queen Victoria. In his own copy of these published extracts from her diary, covering the twenty years immediately after the death of Albert, the Prince Consort (1819–1861), Beerbohm reduced the grieving monarch in her widow’s weeds to a perfectly round piece of tufted drawing-room furniture, legless and squat. Beerbohm, however, never displayed to the public this image or any of the others that he created by drawing over illustrations in the books he owned. His passion for “improving” these volumes was a private one, and he shared the results only with close friends, who would have appreciated his irreverence—especially at the expense of a Queen who represented the high moral seriousness for which they felt only contempt. Presumably, they would have been just as amused by the forged presentation inscription that he added to More Leaves…, which read, “For Mr. Beerbohm the never-sufficiently-to-be-studied writer whom Albert looks down on affectionately, I am sure—From his Sovereign Victoria R. I. Balmoral, 1899.”

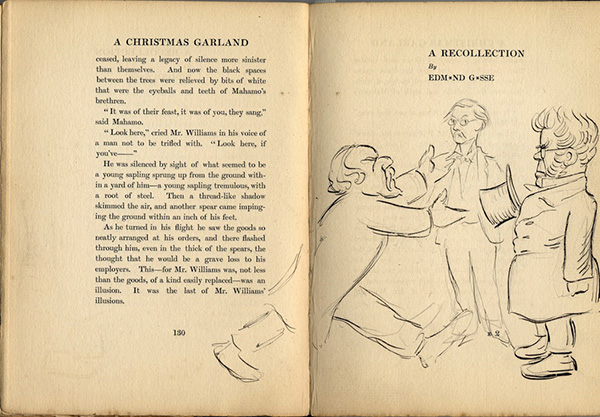

Call it a passion, or call it a compulsion, but Max Beerbohm would not (and perhaps could not) refrain from drawing inside the books that he owned, including those he had written himself. Usually, he “improved” these copies for his own private entertainment; sometimes, he did so as a special treat for the recipients to whom he sent the volumes as presents. Such was the latter case, when he gave his mother, Eliza Draper Beerbohm (ca. 1833–1918), this copy of A Christmas Garland. Among the parodies of celebrated authors that it contained, all tied in some fashion to a holiday setting, was one of the poet and critic Sir Edmund Gosse (1849–1928) in his role as a memoirist. In “A Recollection,” Beerbohm made the voice of Gosse boast of having introduced Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906) to Robert Browning (1812–1889) by bringing the Norwegian playwright along to the poet’s house in Italy for Christmas dinner—a wholly imaginary and ludicrous episode, with Browning “carving the turkey” for his guests. On the pages shown here, Beerbohm has added for his mother’s delight this drawing of all three figures from “A Recollection.”

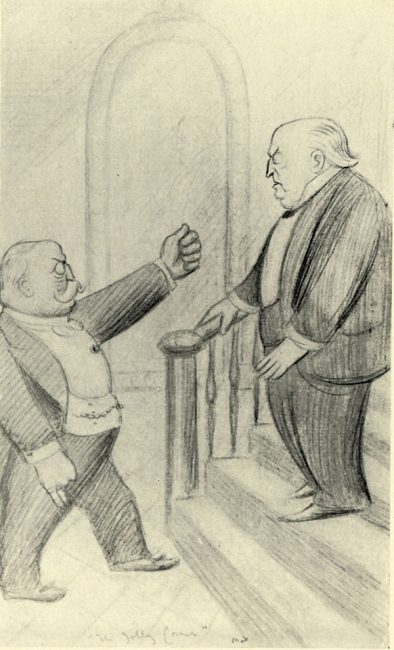

Henry James’s passion for writing long, convoluted sentences that often took half a page to unfurl made him the perfect target for literary parody in Max Beerbohm’s A Christmas Garland (1912). As a caricaturist, Beerbohm also found James to be an irresistible subject for visual lampoons. Alluding to the title of James’s 1908 ghost story, “The Jolly Corner,” in which a man who left New York in his youth returns to his boyhood home and encounters the specter of the self that might have been, Beerbohm created this double portrait of the tale’s author. Here, there is little to choose between the two alternative characters. Both the “American” Henry James and the expatriate, Anglicized version are unattractively bellicose men with sour countenances and overlarge guts. This drawing was at one time the property of the First World War poet and memoirist, Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967).

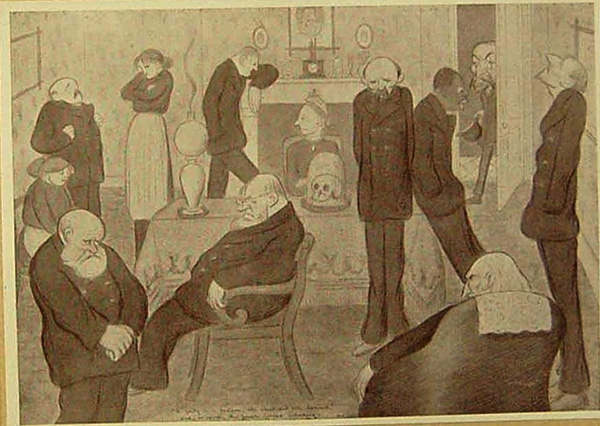

Nothing vexed Max Beerbohm more than unrelieved solemnity or made him more determined to puncture it. He could, for instance, appreciate the artistry that went into the psychologically harrowing novels of Joseph Conrad (1857–1927) and distinguished them from mere tales of adventure in exotic settings. Their explorations, however, of the tortured passions of characters caught in traps of their own making were not to his taste and drove him to mockery. In A Christmas Garland (1912), Beerbohm used the story “Feast”—a racist comedy about a white man who winds up as the holiday-table treat for cannibals—to parody works such as Heart of Darkness (1899). A Party in a Parlour showed his notion of what a festive gathering would look like to the eternally gloomy Conrad: a group of brooding, angst-ridden sailors huddled together in a room where the decorative centerpiece is a skull.

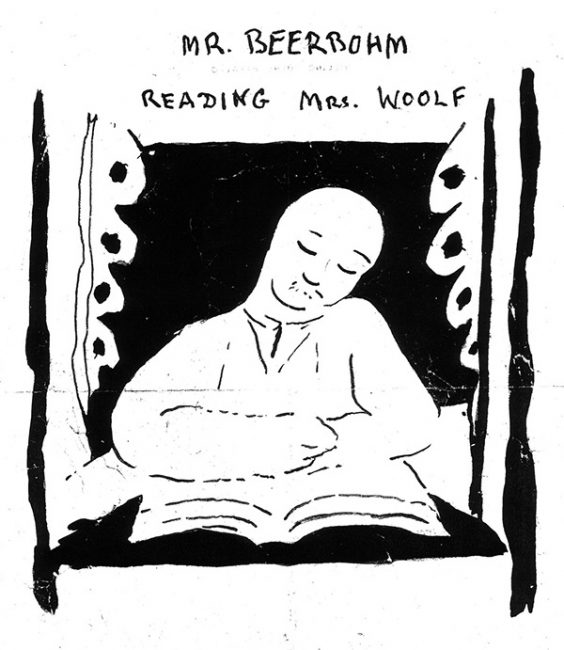

Making a specialty of the works of Sir Max Beerbohm (who was knighted in 1939) has encouraged Mark Samuels Lasner to cross the divide from the nineteenth into the early twentieth century, so that his collection is also rich in materials with Edwardian and even Modernist links. In 1928, Beerbohm wrote to thank a “Miss Payton” for sending him a copy of Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown (1924) by Virginia Woolf (1882–1941)—a pamphlet published by the Hogarth Press with a cover design by Woolf’s sister, the artist Vanessa Bell (1879–1961). Woolf’s passionate manifesto, in which she detailed the grave faults of Beerbohm’s literary contemporaries and called for a new kind of fiction that could capture the inner life of an ordinary woman, met with a surprisingly positive response. Beerbohm told the sender of it that it was “a delightful piece of work” and “a perfect model of how to behave as a lecturer.” On the back of the letter, however, he drew a devastating parody of Bell’s cover image, showing himself attempting to read Woolf’s words and drifting off to sleep.