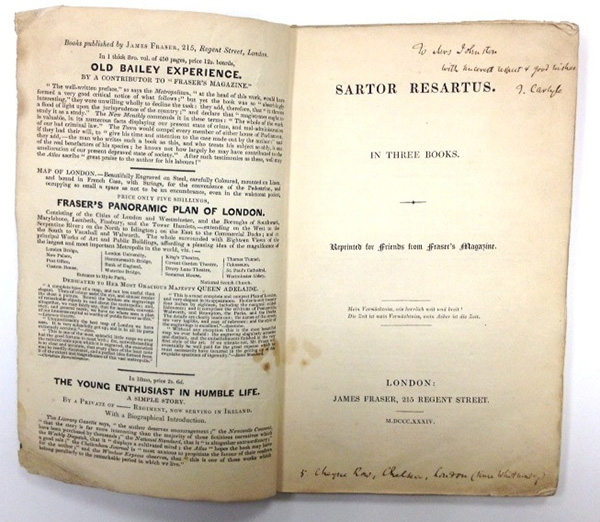

It was a passion for social reform, rather than for fashion, that animated Sartor Resartus and led to Carlyle’s “Philosophy of Clothes,” as articulated by the imaginary German thinker “Teufelsdröckh.” Carlyle’s practice throughout was to shake up complacent Victorian readers and shake them out of their conventional patterns of understanding with abrupt shifts in tone, from satirical to serious. He jolted them even at the level of language, by creating his own idiosyncratic rhetorical style and unpredictable sentence structure. Displayed here is a great rarity: one of fifty-six copies privately printed from the typesetting in Fraser’s Magazine, where Sartor Resartus appeared first in serial form, and the only copy known to have survived with its original wrappers intact. Carlyle presented it to Christian Isobel Johnstone (1781–1857), the Scottish journalist and novelist.

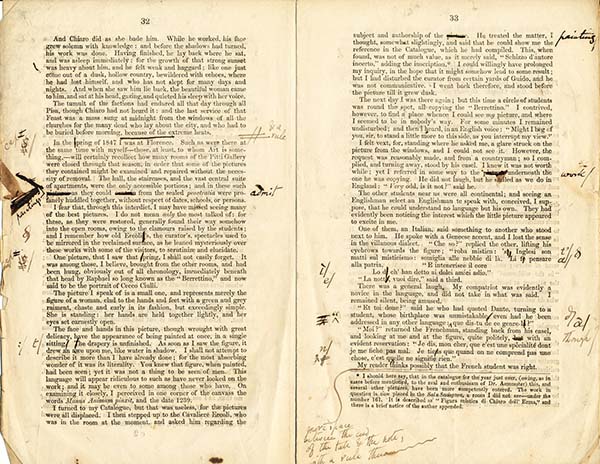

In the nineteenth century, every passion seemed to lead to print, and most causes required a magazine. The year 1848, a time of political revolutions and social upheaval across Europe, saw the founding in England of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Its members were painters and poets who wished to return to the ideals of art before Raphael—before the creation of academic art, with its stultifying rules. Their short-lived manifesto was the Germ, which began and ended in 1850. Among the contributors to its four issues were the artists William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) and Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), along with three members of the Rossetti family: Christina, William Michael (who served as editor), and Dante Gabriel. Shown here are the only surviving proofs for any part of the magazine. This first number included D. G. Rossetti’s short prose work, “Hand and Soul” and poems by “Ellen Allyn” (later spelled as “Alleyn”)—the pseudonym of Christina Rossetti.

Florence Nightingale, 1820–1910. Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It is Not. London: Harrison, [1860]. Rossetti family copy, with the ownership initials “C.L.P.” of Charlotte Lydia Polidori; later owned by her niece, Christina Rossetti, with W. M. Rossetti’s inscription, “W. M. Rossetti from Christina’s books 1894,” and explanatory manuscript note by his daughter, Mary E. Madox Rossetti.

Passionately devoted though she was to her vocation—which involved working to reform the Victorian systems of healthcare and sanitation in their entirety—Florence Nightingale was, in reality, far from the popular image of her as the angelic “Lady with the Lamp” who had ministered to soldiers in the Crimean War. She was hardheaded, politically savvy, and practical. Her Notes on Nursing was a step-by-step manual addressed not to middle-class women looking for a profession—although she almost singlehandedly opened up nursing as a respectable career for ladies—but to all women. Its premise was that proper conduct in the sick-room did not come naturally, based on gender; instead, all women required instruction (her instruction) in such caretaking, for all would at some point have to nurse someone through an illness. This copy of Nightingale’s guide circulated throughout the Rossetti family. It belonged first to Charlotte Polidori (1802–1890), whose sister Eliza had served as one of Nightingale’s volunteers in the Crimea, and then to Polidori’s niece, the poet Christina Rossetti (1830–1894). After the latter’s death, it was in the possession of her surviving brother, the writer William Michael Rossetti (1829–1919), before becoming the property of his daughter.

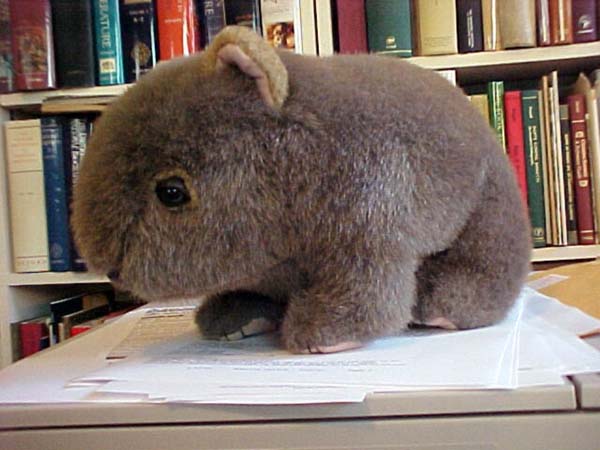

The Mark Samuels Lasner Collection offers splendid resources for the study of the British Pre-Raphaelites—a group of rebellious artists and writers who banded together in 1848 to start a revolution. As well as rejecting conventional artistic standards, they boldly broke with social rules in their private lives. They questioned class and gender hierarchies, refused to treat with reverence what other Victorians took seriously, and deliberately behaved in ways that more conservative contemporaries found shocking or even ridiculous. While they were devoted to sweeping away the ugliness of the present day and, by returning to a medieval past, to creating new forms of beauty, they were also playful figures. One of the more endearing eccentricities of the circle that congregated around the poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) was a shared love of wombats, the Australian marsupials. Rossetti acquired a wombat, which he named “Top” because he thought its corpulent, stubby-looking body resembled that of William Morris (1834–1896), whose nickname was “Topsy.” Although this wombat survived only briefly in the garden of his house in London, it inspired a number of artistic and literary representations. Rossetti’s sister Christina, for instance, included among the sinister creatures selling fruit in her poem “Goblin Market” (1862) one that “like a wombat prowled obtuse and furry.”

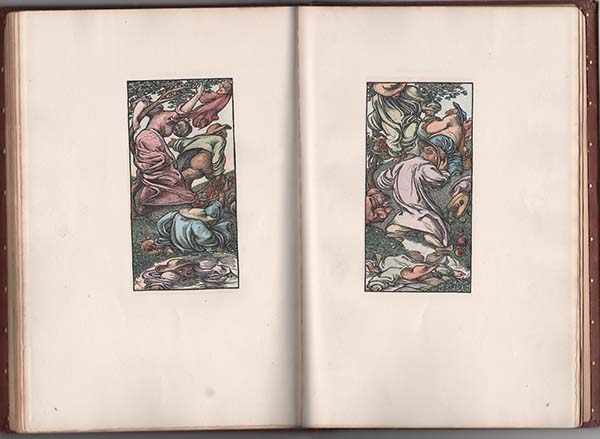

Wombats even had an afterlife in the work of artists associated with the late-nineteenth-century Aesthetic and Decadent movements. When Laurence Housman (1865–1959) illustrated “Goblin Market,” he produced his own sleeker and more sinuous version of one. Shown here is a large paper copy of Goblin Market (1893), bound by the Guild of Women Binders, with Housman’s illustrations hand-colored by a “Miss Gloria Cardew” (which may be a pseudonym). This book was a gift from an anonymous donor to Mark Samuels Lasner. It has joined the Collection’s unofficial mascot, “Murdoch”—named for the Australian academic and journalist, Sir Walter Logie Forbes Murdoch (1874–1970), who wrote admiringly of the Pre-Raphaelites in the 1930s, when they were out of favor with British modernist critics.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1806–1861. Aurora Leigh. London: Chapman and Hall, 1857. Presentation copy, with inscription by the recipient, Ellen Heaton, “Given me by the Authoress. – 1857. – EH. It was sent from the publisher in London, when she was in Florence.”

Quite unfairly, the story of Elizabeth Barrett’s passionate romance and elopement with her fellow poet, Robert Browning, has overshadowed her other passions: for poetry and for social justice. Both were on view in Aurora Leigh, as was her nascent feminism, through its positive representation of Aurora’s quest to be a writer, along with its protest against the stigmatization of Marian Erle, a victim of rape and bearer of a child out of wedlock. The long narrative poem aroused worshipful enthusiasm in its many readers. Among these was Ellen Heaton (1816–1894), a friend to whom Barrett Browning had her publisher send this copy. Heaton, in turn, who moved in Pre-Raphaelite circles, commissioned Arthur Hughes (1832–1915) to paint The Tryst, also known as Aurora Leigh’s Dismissal of Romney (1860), to illustrate one of Heaton’s favorite scenes, in which Aurora chooses to pursue her poetic vocation rather than to marry.

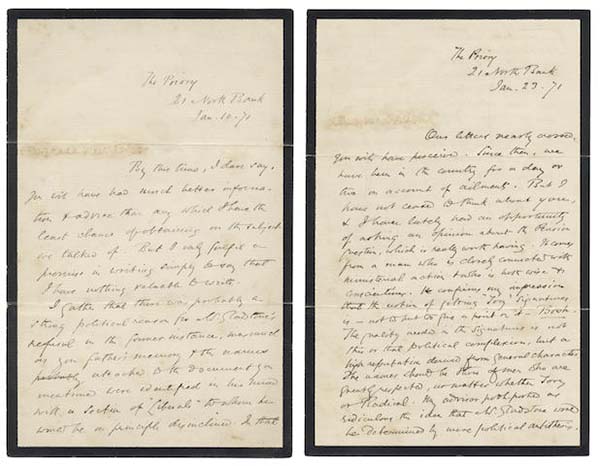

The twenty-five-year-long relationship—without marriage—of the novelist Mary Ann (who also called herself “Marian”) Evans and the critic George Henry Lewes (1817–1878) was hotly debated in their social circles. Eliot herself rejected the idea that it was motivated by so-called low passions. She saw it as an intellectual and spiritual union—a marriage—and often signed her letters “M. E. Lewes,” as she does here. The recipient of these letters was her dear friend Bessie Rayner Parkes (1829–1925), who was also close to another of Eliot’s friends, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1891). Like Bodichon, Parkes was a feminist activist who worked toward the 1870 passage of the first Married Women’s Property Act and supported women’s education. (She was also a poet and editor and, with her husband Louis Belloc, parent of two children who became famous as writers.) Here, George Eliot, in the midst of the serial publication of Middlemarch, takes time to offer advice about her friend’s financial difficulties. The black border of the writing paper probably reflects the long mourning period after the death of Lewes’s son Thornton (1844–1869), whom Eliot helped to nurse during his final illness.

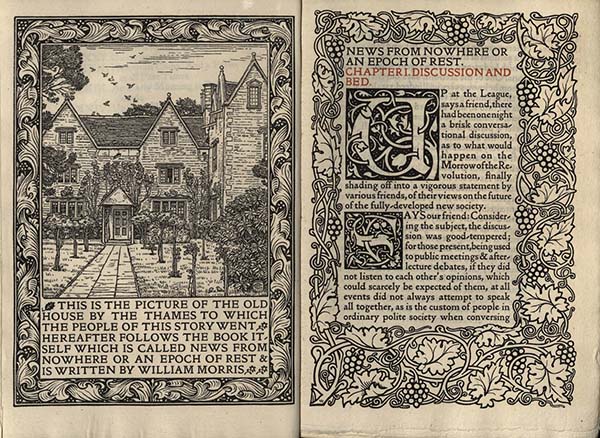

His passion for Socialism; his passion for art and for craftsmanship; his passion for the natural landscape; his passion for Medievalism; his passion for aesthetic book design; his passion for instructing readers; his passion for leading England toward a better future—all these and more informed William Morris’s prose masterwork, the utopian fantasy News from Nowhere. Revising his text from the 1890 appearance in Commonweal of this political dream vision, Morris printed News from Nowhere himself at the Kelmscott Press, which he had founded in 1891 in order to realize his ideal of the Book Beautiful. He presented this copy to his dear friend and long-time Pre-Raphaelite associate, the artist Sir Edward Burne-Jones, who would collaborate with him on the famed Kelmscott edition of Chaucer.

Bernard Shaw, 1856–1950.Typewritten letter to Hall Caine, 21 September 1928.

With his passion for the Pre-Raphaelites and his close association with D. G. Rossetti (1828–1882), the novelist and playwright Sir Thomas Hall Caine (1853–1931) served as a living link between the Victorian and twentieth-century worlds. At the end of Rossetti’s life, Hall Caine had functioned as his secretary and companion, sharing the artist’s London home at 16 Cheyne Walk. In 1928, he issued a new edition of his Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which G. B. Shaw addressed in this letter. Reminding Hall Caine that he had been devoted to William Morris (1834–1896) as a fellow Socialist, rather than as a member of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, the abstemious Shaw made clear that he was no fan of Rossetti or of the artist’s self-indulgent passions, writing, “I like sane people, and loathe drunk people, drugged people, crazy people.”